A workspace featuring documents related to property title verification and due diligence, along with a magnifying glass and a rubber stamp.

Millions lost with no appeals and recovery.

An overseas Filipino wires the full purchase price for land back home. The Deed of Sale is notarized. Receipts are complete. Possession is turned over. Months later, the truth surfaces: the title is fake, the seller had no authority, and the property was never legally for sale. The contract—despite signatures and seals—offers zero protection. Philippine courts are unambiguous on this point.

Contracts do not establish ownership. Titles do.

Real estate fraud in the Philippines does not rely on crude deception. It thrives on familiarity, trust, and incomplete verification. Buyers assume that notarization equals legitimacy. Scammers exploit that assumption. Families lose capital accumulated over decades because the one document that truly matters—the title—was never independently verified.

This guide addresses that failure directly.

You will gain a precise understanding of the legal difference between a Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) and a Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT), how fraudulent and defective titles pass as “clean” in otherwise polished transactions, and the exact verification framework used by licensed brokers, lawyers, and banks before funds are released.

Who This Guide Is For

This guide is written for buyers who cannot afford to get property ownership wrong, including:

- Investors and land buyers who need enforceable ownership, not assumptions

- First-time buyers who want clarity on titles before committing life savings

- Overseas Filipinos (OFWs) purchasing remotely and exposed to elevated fraud risk

- Condominium buyers and investors navigating title issuance delays and association rules

- Foreign buyers operating within ownership limits and transfer restrictions

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Why Property Titles Matter More Than the Property Itself

- The Philippine Torrens Title System Explained (Without the Legal Jargon)

- Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT): Land Ownership Explained

- Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT): Condo Ownership Explained

- TCT vs CCT — A Buyer-Focused Comparison

- The Most Common Property Title Problems in the Philippines

- How to Verify a Property Title in the Philippines (Step-by-Step)

- Government Offices Involved in Title Verification and Transfer

- Taxes, Fees, and Realistic Timelines (Philippines)

- Investment and Lifestyle Implications of TCT vs CCT

- Mini Glossary of Philippine Property Title Terms

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Key Takeaways Buyers Must Remember

- Protect Your Investment Before You Sign Anything

Why Property Titles Matter More Than the Property Itself

A structure can exist. Possession can be granted. Payments can be fully made.

None of these confer ownership under Philippine law.

Ownership is established by title, not by occupancy, contracts, or notarized documents. Courts recognize titles. Banks lend against titles. The Registry of Deeds records titles. Without a valid and verifiable title, a buyer holds no enforceable rights, regardless of how complete the transaction may appear.

This legal reality explains why “clean-looking” deals still collapse in court. Buyers rely on notarized Deeds of Sale, official receipts, or the seller’s representations, only to learn—often after litigation has begun—that the seller had no authority to convey ownership. In such cases, jurisprudence is settled. The Supreme Court consistently rules that buyers bear the burden of due diligence, and “good faith” does not excuse failure to verify the title. Negligence is not protected.

“Consistent Supreme Court rulings have held that buyers of real property must exercise the highest degree of diligence, especially when ownership is evidenced by registered titles.”

The Philippines operates under the Torrens Title System, intended to provide certainty and stability in land ownership. A properly issued Torrens title is considered indefeasible, but that protection is conditional. It applies only when buyers examine the title against official records of the Register of Deeds and investigate annotations, encumbrances, and ownership history. The system safeguards those who verify, not those who assume.

Seasoned buyers understand this hierarchy. The property attracts interest, but the title determines ownership, transferability, and investment security. Everything else—location, structure, finishes, even price—is secondary. Ignore the title, and the transaction rests on appearances rather than law.

Key aspects of property ownership: Title, Legal Ownership, Transferability, and Investment Security.

Understanding ownership conceptually is not enough—the real question is how Philippine law actually records, recognizes, and enforces it.

The Philippine Torrens Title System Explained (Without the Legal Jargon)

The Torrens Title System is the legal backbone of property ownership in the Philippines. It exists for one purpose: to make ownership definitive, traceable, and enforceable. Under this system, ownership is not proven by possession, contracts, or payment—but by registration. If your name is not properly registered on the title with the Register of Deeds, you are not the legal owner. Full stop.

This is why the Torrens system carries so much weight in courts, banks, and government agencies. A Torrens title is intended to be the single, authoritative source of truth. It eliminates guesswork. It prevents endless disputes. It allows the market to function with certainty.

However, buyers often misunderstand what the system actually guarantees.

What the Torrens System Is — and What It Is Not

A Torrens title is often described as indefeasible, meaning it cannot be easily challenged once validly issued and registered. This is correct—but incomplete.

Indefeasible does not mean immune to fraud. It does not mean every title presented to you is automatically valid. And it certainly does not mean buyers are relieved of responsibility.

Titles can still be defective if:

- They were issued based on falsified documents

- They were transferred by someone without legal authority

- They contain undiscovered annotations, liens, or adverse claims

- The buyer failed to examine official Registry of Deeds records

When these defects surface, courts do not rescue careless buyers. The Torrens system protects the integrity of registration—not negligence in verification.

This is why buyers sometimes lose cases despite believing they purchased a property with a “clean title”. The title may look authentic, but the process leading to its transfer was flawed, and the buyer failed to uncover that flaw before purchasing.

“The Torrens system secures registered ownership, but it does not insure buyers against their own failure to investigate.”

Buyer Responsibility Under Philippine Jurisprudence

Philippine Supreme Court decisions are consistent and uncompromising: buyers of real property are expected to exercise a high degree of diligence. Ordinary prudence is not enough. Real estate transactions demand heightened scrutiny because of their financial and legal impact.

“Philippine jurisprudence is clear: failure to verify ownership records is treated as buyer negligence, regardless of intent or claimed good faith.”

Courts repeatedly reject defenses based on:

- Seller assurances

- Long possession

- Notarized deeds alone

- Claims of good faith unsupported by verification

The law expects buyers to go beyond the surface. This includes securing a Certified True Copy from the Register of Deeds, reviewing annotations and encumbrances, confirming the seller’s identity and authority, and verifying that the title being transferred matches official records in every material detail.

In short, the Torrens system is not a safety net for passive buyers. It is a framework that rewards those who verify and penalizes those who assume. Understanding this distinction is not academic—it is the difference between secure ownership and irreversible loss.

| Buyer Assumption | Legal Reality |

|---|---|

| Notarized contract is enough | Title verification is mandatory |

| Seller seems trustworthy | Authority must be proven |

| “Clean title” means safe | Register of Deeds records must be checked |

Once the system is clear, the next step is understanding how ownership is expressed on paper—starting with land itself.

Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT): Land Ownership Explained

A Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) is the most powerful document in Philippine real estate. It does not merely show who paid for the property. It establishes who the law recognizes as the owner of the land—with enforceable rights against everyone else.

If ownership is ever challenged, courts do not look at possession, receipts, or verbal agreements. They look at the TCT.

What a TCT Represents Legally

A TCT represents absolute ownership of land, subject only to limitations expressly written on the title or imposed by law. This ownership includes the right to use, lease, sell, mortgage, or transfer the property.

However, ownership under a TCT is not unlimited. It is subject to:

- Zoning laws and land-use regulations

- Easements and right-of-way provisions

- Existing liens, mortgages, or court orders annotated on the title

A TCT applies to properties where land ownership is transferred, including:

- Vacant lots, whether residential, agricultural, or commercial

- House-and-lot properties, where the structure sits on titled land

- Townhouses with land ownership, where the buyer owns the lot, not just the unit

This distinction matters. A buyer who assumes land ownership when only unit rights are being transferred risks acquiring far less than expected.

Key Information Found on a TCT

Every TCT contains critical details that define the extent and quality of ownership. Buyers should review each with precision:

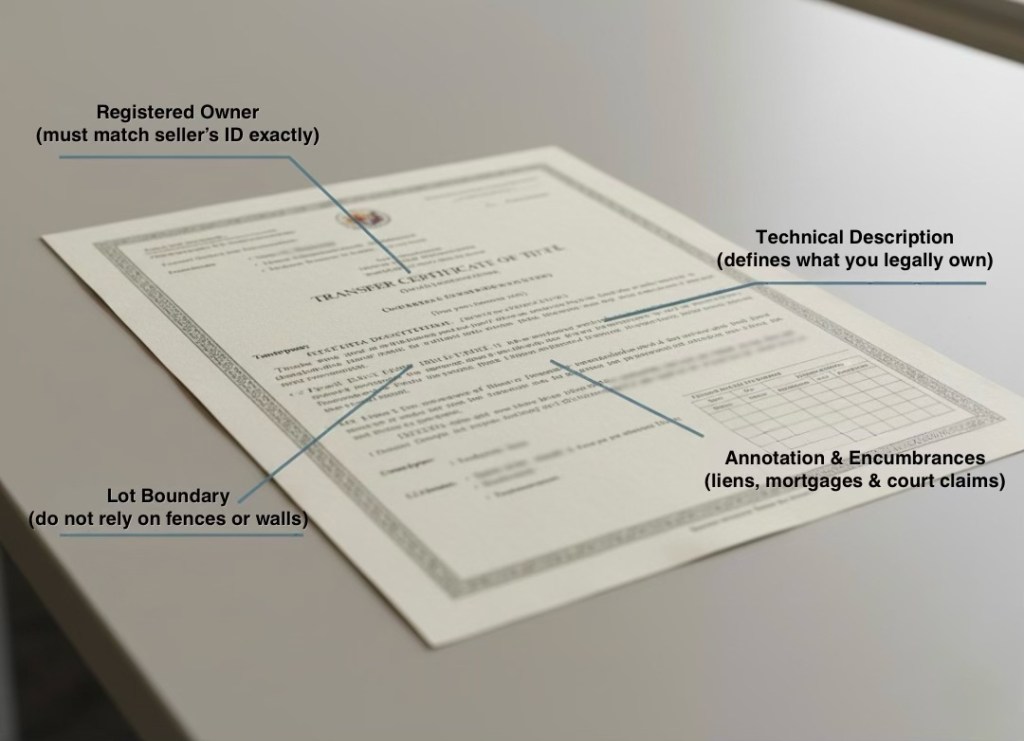

Detailed view of a sample Transfer Certificate of Title, highlighting key sections such as Registered Owner, Technical Description, Lot Boundary, and Annotation & Encumbrances.

Registered owner’s name

This must exactly match the seller’s identity. Even minor discrepancies can delay or invalidate a transfer.

Technical description

A survey-based description defining the property’s precise measurements and location. This governs what you legally own—not fences or visible boundaries.

Lot boundaries

These specify adjacency to neighboring properties and public roads, and are crucial in detecting encroachments or overlaps.

Annotations and encumbrances

This section reveals mortgages, liens, adverse claims, court cases, or restrictions affecting the property. Ignoring this area is one of the most common—and costly—buyer mistakes.

A “clean” title is not determined by appearance. It is determined by what is written, recorded, and verified.

Common TCT Red Flags Buyers Miss

Many problematic transactions appear legitimate on the surface. The issues emerge only when buyers fail to recognize these warning signs:

Inherited properties without settlement of estate

Heirs cannot sell land unless the estate has been legally settled. Sales made without this process are highly vulnerable to challenge.

Informal or unregistered transfers

Long possession or private agreements do not create ownership. If the seller’s name is not on the title, authority must be proven—without exception.

Boundary discrepancies

Fences, walls, or driveways often do not align with the technical description. This can lead to encroachment disputes or reduced land area.

Multiple claimants

Properties with overlapping titles, adverse claims, or unresolved ownership disputes expose buyers to litigation, regardless of payment or possession.

Experienced buyers treat these red flags as non-negotiable deal breakers until fully resolved.

Red Flag Checklist — Stop Before You Buy

If any of the following apply, pause the transaction and investigate:

❗ Seller’s name does not exactly match the registered owner on the title

❗ Property is inherited, but no settlement of estate is completed

❗ Sale is being done through a representative without a valid SPA

❗ Title has annotations (mortgage, lien, court case) not fully explained

❗ Boundaries on the ground do not match the technical description

❗ Seller resists providing a Certified True Copy from the Register of Deeds

If you’re seeing any of these red flags in a property you’re considering, professional review should happen before any payment is made.

Understanding a TCT is not optional. It is the foundation of land ownership—and the first line of defense against irreversible loss.

Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT): Condo Ownership Explained

Condominium ownership in the Philippines is widely misunderstood—and that misunderstanding costs buyers time, money, and legal leverage.

When you buy a condominium, you are not buying land. You are buying a defined space within a building, together with specific rights and obligations governed by law and by the condominium corporation. These rights are evidenced by a Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT). Without it, ownership is incomplete.

What You Actually Own When You Buy a Condo

A detailed cross-section of a condominium building, illustrating private unit areas, shared structural components, plumbing, and common areas under RA 4726.

A CCT defines three interrelated interests that together form condominium ownership:

Unit boundaries

Your ownership is limited to the space described in the title—typically measured from the inner surfaces of walls, floors, and ceilings. Anything outside those boundaries is not exclusively yours.

Interest in common areas

Along with your unit, you acquire a proportionate, undivided interest in common areas such as hallways, lobbies, elevators, structural components, and shared amenities. This interest is inseparable from the unit and cannot be sold independently.

Membership in the condominium corporation

Every unit owner is automatically a member of the condominium corporation, which manages the building, enforces rules, collects dues, and represents owners in legal and administrative matters. Your rights and obligations extend beyond your unit.

Understanding this structure is essential. Many disputes arise not from the unit itself, but from misunderstandings about common areas, voting rights, and shared responsibilities.

The Role of the Master Deed & Declaration of Restrictions

The Master Deed and the Declaration of Restrictions (DDR) are foundational documents that govern the entire condominium project.

They define:

- Unit boundaries and numbering

- Allocation of common area interests

- Permitted and prohibited uses

- Rules on leasing, alterations, and pets

- Rights and powers of the condominium corporation

These documents matter because the CCT does not exist in isolation. It draws its authority from them.

A common buyer blind spot is failing to review the DDR before purchase. Restrictions on short-term rentals, renovations, or commercial use can materially affect both lifestyle and investment returns. A unit may be legally owned—but heavily restricted.

Foreign Ownership Rules and Title Implications

Condominium title issuance delay is one of the most common—and underestimated—risks in vertical developments. Condominium titles come with risks unique to vertical developments, with condominium title issuance delay being one of the most common and underestimated:

Once the foreign ownership threshold is reached:

- Additional units cannot be transferred to foreign buyers

- Developers and sellers may be legally barred from issuing or transferring CCTs to foreigners

- Transactions may stall despite full payment or signed contracts

This is why some foreign buyers discover—too late—that a unit they contracted to buy cannot legally be titled in their name. Without a valid CCT, ownership remains incomplete and vulnerable.

Common CCT-Specific Issues Buyers Encounter

Philippine law allows foreigners to own condominium units, but only up to 40% of the total project. This limit is strict and title-based.

Developer delays in title issuance

CCTs are often issued years after turnover due to incomplete project documentation, unpaid taxes, or unresolved compliance issues. Until the CCT is released, ownership remains provisional.

Unpaid association dues

Outstanding dues attach to the unit, not the owner. Buyers who fail to verify balances may inherit arrears that must be settled before transfer.

Parking title confusion

Parking slots may be titled separately, assigned by contract only, or classified as common areas. Assuming parking ownership without documentation leads to disputes and resale complications.

CCT vs Developer Contract — Why Titles Matter More Than Turnover Papers

| Developer Contract | Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT) |

|---|---|

| Proof of purchase or payment | Proof of legal ownership |

| Issued by the developer | Issued and registered by the Register of Deeds |

| Allows unit turnover or occupancy | Allows transfer, resale, and financing |

| Can exist without title issuance | Cannot exist without completed registration |

| Enforceable mainly against the developer | Enforceable against the world |

Banks, courts, and government agencies recognize titles—not turnover documents.

Experienced buyers treat the CCT with the same rigor as a land title. Contracts promise future ownership. The CCT proves it.

A condominium purchase is only complete when the CCT is issued, verified, and transferred. Anything less is an obligation—not ownership.

TCT vs CCT — A Buyer-Focused Comparison

Both Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) and Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT) are Torrens titles, but they represent very different ownership structures, risk profiles, and buyer responsibilities. Treating them as interchangeable is a common—and expensive—mistake.

The right title depends on what you are buying, how you intend to use it, and how much risk you are prepared to manage.

TCT vs CCT: What Buyers Need to Know

| Feature | TCT (Transfer Certificate of Title) | CCT (Condominium Certificate of Title) |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership scope | Full ownership of the land and everything built on it, subject to legal restrictions and annotations | Ownership of a specific condo unit plus an undivided interest in common areas |

| Property type | Vacant lots, house-and-lot properties, townhouses with land ownership | Condominium units in vertical or horizontal developments |

| Transfer complexity | Generally more straightforward, but heavily dependent on clean ownership history and boundary accuracy | More complex due to developer compliance, condo corporation records, and project-level restrictions |

| Risk profile | Higher exposure to title fraud, inheritance issues, boundary disputes, and double sales | Higher exposure to developer delays, unpaid dues, foreign ownership caps, and document backlogs |

| Ideal buyer | End-users seeking permanence, long-term investors, families, land bankers | Urban end-users, rental-focused investors, OFWs, and foreign buyers (subject to ownership limits) |

How Buyers Should Use This Comparison

A TCT offers control and permanence—but demands rigorous due diligence on ownership history and land boundaries. A CCT offers accessibility and convenience—but requires scrutiny of developer compliance, condominium governance, and foreign ownership limits.

Neither is inherently safer. Each carries risks that only become manageable when understood early.

Recognizing these risks is only useful if you know how to eliminate them before money changes hands.

The Most Common Property Title Problems in the Philippines

Property title problems in the Philippines are rarely accidental. They follow repeatable patterns—and buyers who don’t recognize them early often discover the issue only after money has changed hands and options have disappeared.

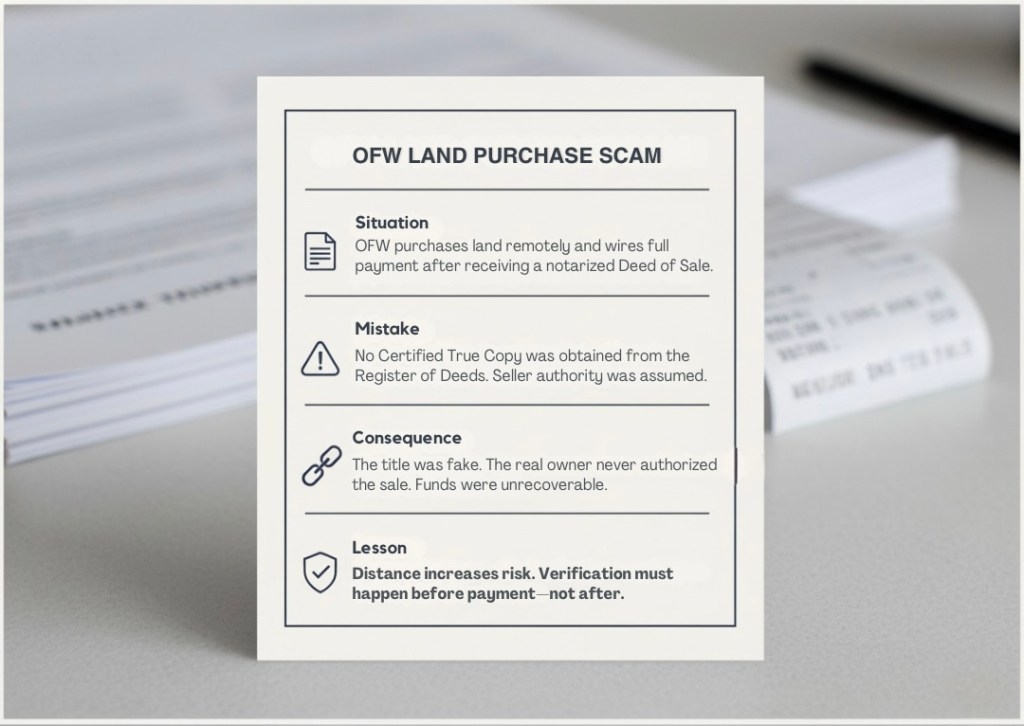

An informative card detailing the risks of OFW land purchase scams, highlighting the situation, common mistakes, consequences, and lessons learned.

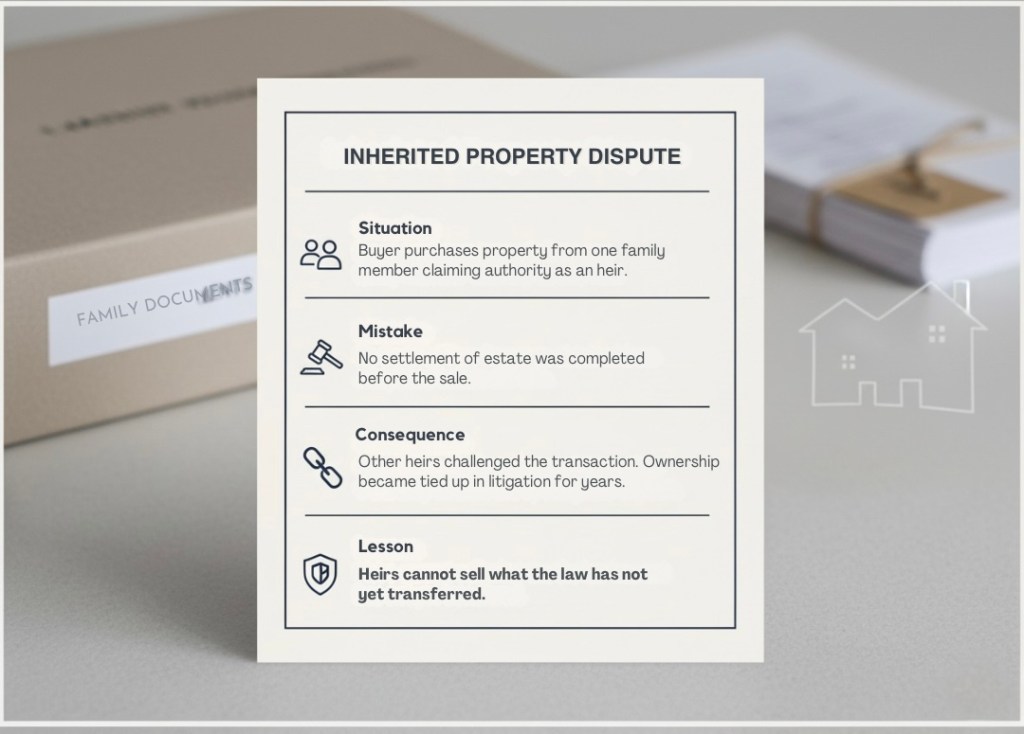

Overview of an inherited property dispute highlighting key points: situation, mistake, consequence, and lesson.

Overview of condo title delay including situation, mistake, consequence, and lesson.

Understanding these risks is not pessimism. It is basic transaction intelligence.

Fake or Spurious Titles

Counterfeit titles remain one of the most damaging forms of real estate fraud. These documents are designed to look legitimate—complete with seals, signatures, and convincing paper quality—but are not registered in the Register of Deeds.

Buyers who rely solely on the owner’s duplicate copy, without securing a Certified True Copy (CTC), expose themselves to total loss. Once payment is made, recovery is rare. Courts cannot validate a title that never existed in official records.

Selling Without Authority

A valid title does not automatically mean a valid seller.

Common scenarios include:

- Relatives selling property still registered under a deceased owner

- Agents or family members selling without a valid Special Power of Attorney (SPA)

- Co-owners selling without the consent of other registered owners

In these cases, the sale may be void or voidable, regardless of payment or possession. Authority must be proven—not assumed.

Heir Disputes and Estate Issues

Inheritance is one of the most overlooked sources of title problems.

When a property owner dies, ownership does not automatically transfer to heirs. Without judicial or extrajudicial settlement of estate, heirs have no individual authority to sell. Transactions conducted before settlement are vulnerable to challenge by excluded heirs—even years later.

What looks like a family agreement can quickly turn into multi-party litigation.

Unpaid Taxes and Hidden Liens

Titles can carry financial obligations that survive the sale.

These include:

- Unpaid real property taxes

- Existing mortgages

- Court-ordered liens or adverse claims

Because these are typically reflected in the annotations section of the title, buyers who fail to review this area carefully may inherit liabilities they never agreed to assume.

Clerical Errors That Delay Transfers for Years

Not all problems involve fraud. Some involve errors that are just as costly.

Misspelled names, incorrect technical descriptions, or mismatched lot numbers can delay title transfers for months—or years. Corrections require formal procedures, supporting documents, and multiple agency approvals. Until corrected, transfer and financing are often impossible.

Bureaucratic Delays Buyers Underestimate

Even “clean transactions” can stall due to administrative backlogs.

Delays commonly occur at:

- The Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR)

- Register of Deeds

- Local Assessor’s and Treasurer’s Offices

Missing documents, inconsistent records, or late tax payments can extend processing timelines far beyond buyer expectations. What was assumed to be a 3–6 month process can stretch into years.

Case Snapshots: How These Problems Play Out

Case 1: OFW Scam

- Situation: OFW purchases land remotely through a representative

- Mistake: No CTC obtained; seller authority assumed

- Consequence: Title discovered to be fake; funds unrecoverable

- Lesson: Distance amplifies risk—due diligence is a legal obligation, not a preference.

Case 2: Family Inheritance Dispute

- Situation: Buyer purchases property from one heir

- Mistake: No settlement of estate completed

- Consequence: Sale challenged by other heirs; prolonged litigation

- Lesson: Heirs cannot sell what the law has not yet transferred

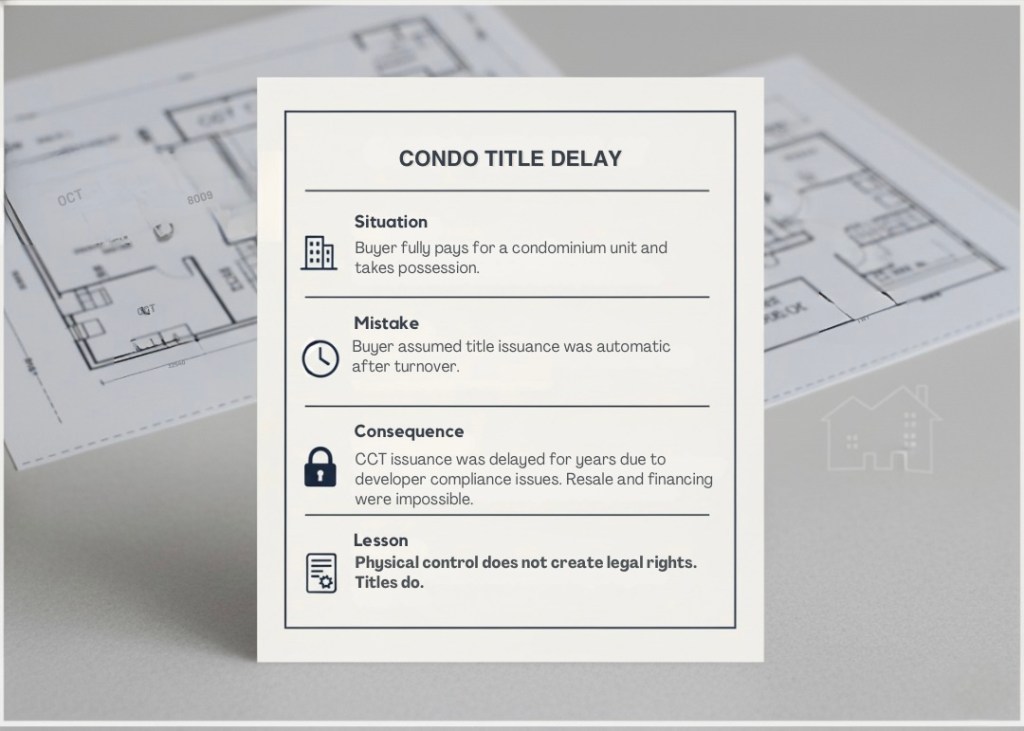

Case 3: Condo Title Delay

- Situation: Condo unit fully paid and occupied

- Mistake: Buyer assumed CCT issuance was automatic

- Consequence: Title delayed for years due to developer compliance issues

- Lesson: Physical control does not create legal rights; titles must be issued and transferred.

Recognizing these risks is only useful if you know how to eliminate them before money changes hands. Title problems are predictable. Losses are avoidable. The difference is whether the buyer recognizes these patterns before committing—not after.

How to Verify a Property Title in the Philippines (Step-by-Step)

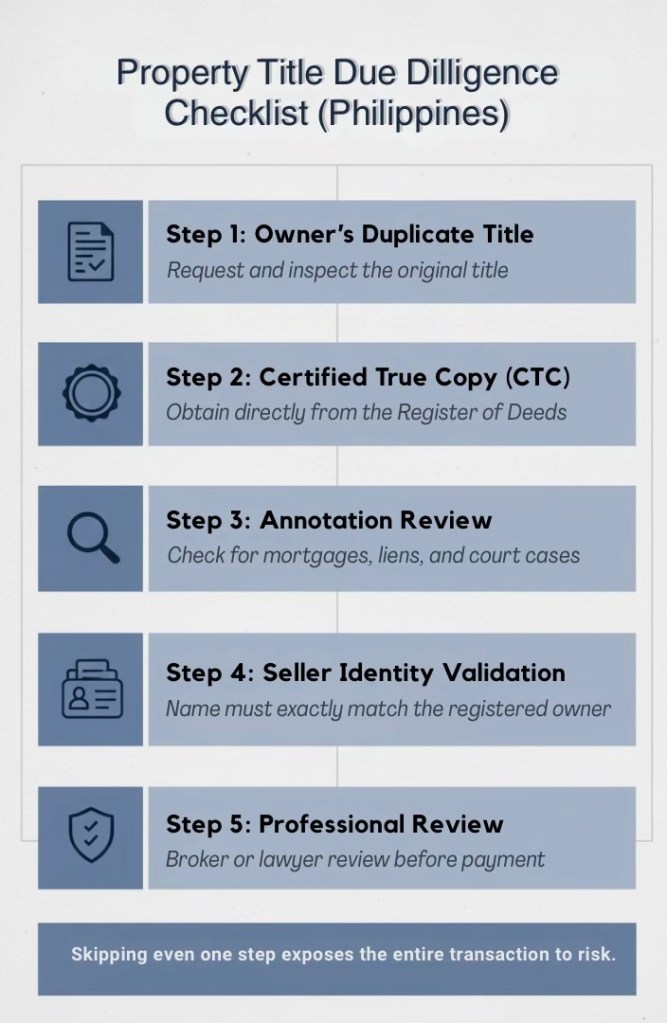

Title verification is not a courtesy. It is a mandatory risk-control process. Licensed brokers, lawyers, and banks follow the same framework for property title verification Philippines buyers rely onbefore any funds are released. Buyers who skip even one step expose themselves to avoidable loss.

Property Title Due Diligence Checklist for the Philippines outlining crucial steps in the verification process.

Download the Property Title Verification Checklist

Get the printable Property Title Verification Checklist (Philippines Edition)—the same due diligence framework used by licensed brokers and banks to verify ownership and avoid costly title issues.

What you’ll get:

- A step-by-step checklist you can use during actual transactions

- Clear red flags that tell you when to pause a deal

- A practical tool for buyers, investors, and OFWs purchasing remotely

📩 Enter your email to receive the checklist instantly.

This checklist is for serious buyers who want certainty—not assumptions.

“This is the same verification standard required by banks before approving real estate loans or releasing mortgage proceeds.”

This step-by-step property title verification Philippines framework is the same process used by banks and licensed professionals.

Step 1: Examine the Owner’s Duplicate Title

Request the original owner’s duplicate copy of the title. Do not accept scans or photocopies as substitutes.

Check for:

- Signs of alteration, erasures, or inconsistencies

- Correct paper type, serial numbers, and registry markings

- Exact matching of the owner’s name with the seller’s identification

This step filters out the most obvious fakes, but it does not confirm authenticity on its own.

Step 2: Secure a Certified True Copy (CTC) from the Register of Deeds

This is the most critical step.

Obtain a CTC directly from the Register of Deeds (RD) where the property is located. The CTC confirms whether the title exists in official records and reflects the latest annotations—this Register of Deeds title check is the only reliable way to confirm authenticity.

“Courts consistently defer to records maintained by the Register of Deeds over privately held copies or notarized instruments.”

If the seller resists this step, walk away. There is no legitimate reason to object.

Step 3: Review Annotations and Encumbrances Carefully

The annotations section determines whether the property is free to sell.

Look for:

- Mortgages and bank liens

- Adverse claims

- Court cases or notices of lis pendens

- Restrictions or easements

Any existing encumbrance must be resolved—or contractually addressed—before purchase. Ignoring annotations is equivalent to buying debt and litigation with the property.

Step 4: Validate the Seller’s Identity and Authority

Confirm that:

- The seller’s name exactly matches the registered owner

- Government-issued IDs align with the title

- The seller is not acting merely as a representative unless legally authorized

Name discrepancies, even minor ones, can delay or invalidate title transfer.

Step 5: Verify the Special Power of Attorney (SPA), If Applicable

If someone is selling on behalf of the owner, require a notarized SPA.

The SPA must:

- Specifically authorize the sale of the property

- Identify the property clearly

- Be valid, current, and properly notarized

General or vague authorizations are insufficient and routinely rejected by registries and courts.

Step 6: Obtain Professional Review Before Payment

Before releasing funds, have the documents reviewed by:

- A licensed real estate broker experienced in due diligence

- A real estate lawyer, especially for complex or high-value transactions

Professionals identify risks buyers typically miss—and the cost of review is insignificant compared to the cost of a failed transaction.

Verification is not paranoia. It is professionalism. Buyers who follow this framework do not rely on trust—they rely on records.

Government Offices Involved in Title Verification and Transfer

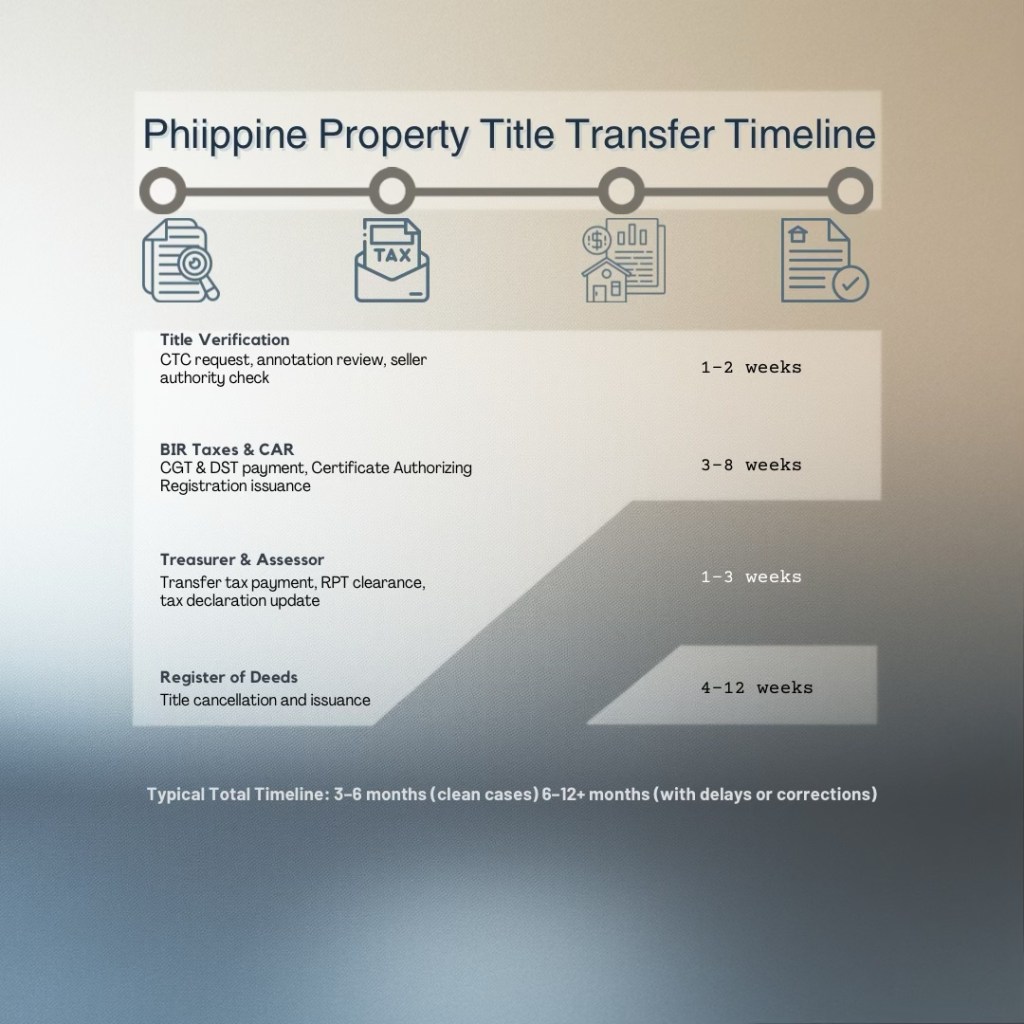

Philippine Property Title Transfer Timeline outlining necessary steps and estimated durations.

Property ownership in the Philippines is not finalized in a single office, and understanding the land title transfer process Philippines buyers must navigate is essential to avoiding delays and invalid registrations. It moves through a defined sequence of government agencies, each with a specific legal function. Delays, failed transfers, and invalid registrations usually occur when buyers misunderstand—or bypass—this process. Understanding the land title transfer process Philippines buyers must follow is essential to avoiding delays and invalid transfers.

Knowing who does what is essential to controlling timelines and risk.

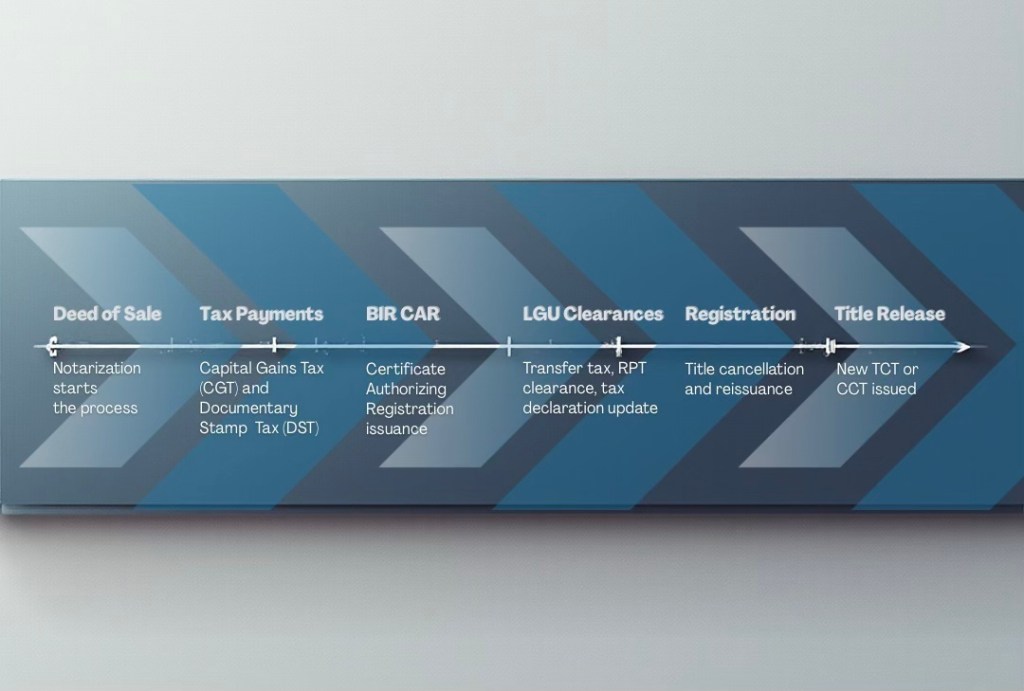

Register of Deeds (RD)

The Register of Deeds is the most critical office in any real estate transaction. It is the official custodian of land and condominium titles under the Torrens system.

Its functions include:

- Issuing Certified True Copies (CTCs) for title verification

- Recording deeds of sale, mortgages, and other registrable instruments

- Cancelling old titles and issuing new TCTs or CCTs in the buyer’s name

No transfer is legally effective until it is recorded with the RD. Until then, ownership remains unchanged—regardless of payment or possession.

Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR)

The BIR enforces tax compliance before a title can be transferred.

Key responsibilities:

- Assessment and collection of Capital Gains Tax (CGT) or Creditable Withholding Tax (CWT)

- Collection of Documentary Stamp Tax (DST)

- Issuance of the Certificate Authorizing Registration (CAR)

Without a CAR, the Register of Deeds will not process title transfer. This office is a common source of delay when documents are incomplete or inconsistent.

Local Assessor’s Office

The Local Assessor updates the property’s tax records after transfer.

Its role includes:

- Issuing and updating the Tax Declaration

- Recording the property’s assessed value under the new owner

- Coordinating property classification and usage

While the Tax Declaration is not proof of ownership, inconsistencies between the title and tax records often trigger transfer delays.

Treasurer’s Office

The Local Treasurer’s Office ensures that all local taxes are settled.

Responsibilities include:

- Issuing Real Property Tax (RPT) Clearances

- Collecting Transfer Tax

- Confirming there are no outstanding local tax liabilities

Unpaid taxes attach to the property, not the owner. Clearance from this office is mandatory before registration.

HOA / Condominium Corporation

For condominiums and properties within subdivisions, the HOA or Condominium Corporation plays a gatekeeping role.

They typically:

- Issue clearances for unpaid dues

- Confirm compliance with association rules

- Endorse transfers and updates to membership records

Failure to secure HOA or condo clearances can delay registration and prevent title release, especially for CCTs.

Property transfers fail not because buyers lack intent—but because they underestimate process. Understanding these offices transforms confusion into control.

Even with perfect documents and compliance, ownership is not complete until the taxes are paid and the timelines are understood.

Taxes, Fees, and Realistic Timelines (Philippines)

Most delays occur during BIR processing and Register of Deeds registration.

Property transfers in the Philippines do not fail because buyers refuse to pay taxes. They fail because buyers misunderstand when, how much, and how long the process actually takes. Underestimating this stage leads to expired documents, penalties, and multi-year delays that could have been avoided with accurate expectations.

This is what buyers must plan for—without illusions.

Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

For most secondary market sales, the seller is required to pay Capital Gains Tax, equivalent to 6% of the higher of:

- The selling price, or

- The property’s zonal or fair market value

CGT must be paid within 30 days from notarization of the Deed of Sale. Late payment results in surcharges, interest, and complications that immediately stall title transfer.

Documentary Stamp Tax (DST)

The Documentary Stamp Tax is assessed at 1.5% of the higher of the selling price or zonal value.

DST is typically paid by the buyer, although this can be contractually negotiated. Like CGT, DST must be settled promptly, as it is a prerequisite for securing the Certificate Authorizing Registration (CAR)from the BIR.

Transfer Tax

The Transfer Tax is imposed by the local government unit (LGU) where the property is located.

- Rates typically range from 0.5% to 0.75% of the property value

- Paid to the Local Treasurer’s Office

- Required before registration with the Register of Deeds

Rates and processing timelines vary by city or municipality, adding another layer of unpredictability.

Registration Fees

Once all taxes are paid and clearances issued, the Register of Deeds collects registration fees to cancel the old title and issue a new TCT or CCT.

Fees depend on property value and are computed based on a sliding scale. Payment does not guarantee immediate release—only inclusion in the processing queue.

Actual Timelines: Expectation vs Reality

On paper, a “clean transfer” can be completed in 3 to 6 months.

In practice:

- BIR processing alone may take 1–3 months

- Registry backlogs can extend issuance by several additional months

- Any error, missing document, or unpaid tax can push completion to 12–24 months or more

Buyers who plan around “best-case scenarios” are routinely disappointed. Those who plan for delays remain in control.

In Philippine real estate, speed is the exception—not the rule. Budget for taxes. Prepare for delays. Ownership rewards those who plan for reality, not optimism.

Investment and Lifestyle Implications of TCT vs CCT

| Buyer Type | Preferred Title | Primary Advantage | Key Risk to Manage |

|---|---|---|---|

| End-Users | TCT | Full land ownership and long-term control | Boundary issues, inheritance complications |

| Investors | TCT or CCT | Appreciation (TCT) or rental liquidity (CCT) | Title defects or association restrictions |

| OFWs | CCT | Easier management and rental potential | Title issuance delays, remote verification risk |

| Foreign Buyers | CCT | Legal ownership within statutory limits | 40% ownership cap, transfer restrictions |

| Retirement Buyers | TCT or CCT | Stability (TCT) or convenience (CCT) | Maintenance burden or condo rule changes |

Choosing between a TCT and a CCT is not a technical decision. It is a strategic one. Each title type shapes how the property can be used, financed, leased, transferred, and ultimately monetized. Buyers who ignore this alignment often end up with assets that conflict with their actual goals.

The title should fit the buyer—not the other way around.

Which Title Fits Which Buyer?

End-Users

Buyers planning to live in the property long-term typically benefit from a TCT. Land ownership provides permanence, control over modifications, and insulation from association rule changes. It suits families prioritizing space, stability, and generational use. That said, urban end-users who value convenience over control may still prefer a CCT, provided they fully understand condo restrictions.

Investors

Investment strategy determines the title. TCTs favor land banking and long-term appreciation, particularly in growth corridors where land scarcity drives value. CCTs, on the other hand, support income-focused strategies—shorter holding periods, rental yield, and liquidity—assuming association rules and market demand align.

OFWs

OFWs often balance capital growth with manageability. CCTs are attractive due to centralized management, lower maintenance burden, and rental potential. However, remote buyers must be vigilant about developer compliance and title issuance timelines. OFWs seeking legacy assets or future family use may find TCTs more aligned with long-term plans.

Foreign Buyers

Foreign nationals are legally restricted from owning land, making CCTs the primary option. Even then, ownership is capped by the 40% foreign ownership limit per project. This makes title verification and developer disclosures critical. Without a transferable CCT, ownership cannot be perfected.

Retirement Buyers

Retirees prioritize security, accessibility, and predictability. TCTs offer autonomy and long-term certainty, ideal for those settling permanently. CCTs appeal to retirees seeking convenience, security, and reduced upkeep—especially in walkable, amenity-rich locations.

The best property is not the most attractive one on paper. It is the one whose title structure supports your lifestyle, investment horizon, and risk tolerance. Choose accordingly.

Mini Glossary of Philippine Property Title Terms

Real estate transactions in the Philippines are saturated with legal and technical language. Misunderstanding even one term can derail a deal or expose a buyer to unnecessary risk. This glossary translates the most critical title-related terms into plain, practical language.

Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT)

A land title issued for properties involving land ownership, such as vacant lots, house-and-lot properties, and townhouses with land. It is the legal proof of ownership recognized by courts, banks, and government agencies.

Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT)

A title issued for condominium units. It proves ownership of a specific unit and an undivided interest in the building’s common areas. It does not confer land ownership.

Torrens Title

A title registered under the Torrens system, designed to provide certainty of ownership. Once properly issued and registered, it becomes the authoritative record of ownership—but only when due diligence is exercised.

Certified True Copy (CTC)

An official copy of a title issued by the Register of Deeds. This is the definitive reference for verifying whether a title is genuine and current. Buyer verification is incomplete without it.

Annotations / Encumbrances

Notes written on the title indicating liens, mortgages, court cases, restrictions, or claims affecting the property. These directly impact whether the property can be sold or transferred.

Deed of Sale

The notarized document transferring ownership from seller to buyer. Important—but ineffective until registered and supported by a valid title.

Special Power of Attorney (SPA)

A legal document authorizing someone to sell or transact on behalf of the property owner. It must be specific, valid, and properly notarized to be recognized.

Settlement of Estate

The legal process by which ownership of a deceased person’s property is transferred to heirs. Without it, heirs generally lack authority to sell.

Tax Declaration

A local government record used for taxation purposes. It is not proof of ownership, but inconsistencies with the title often cause transfer delays.

Real Property Tax (RPT) Clearance

A certification that all local property taxes have been paid. Unpaid taxes follow the property—not the owner.

Certificate Authorizing Registration (CAR)

Issued by the Bureau of Internal Revenue, this document confirms that required taxes have been paid and authorizes the Register of Deeds to process the title transfer.

Master Deed and Declaration of Restrictions (DDR)

Foundational documents governing condominium projects. They define unit boundaries, common areas, usage rules, and owner obligations.

Clarity eliminates risk. Understanding these terms transforms real estate from a guessing game into a controlled transaction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can foreigners own land in the Philippines?

No. Philippine law restricts land ownership to Filipino citizens and to corporations that are at least 60% Filipino-owned. Foreigners cannot own land directly under any circumstance.

However, foreigners may legally own condominium units, provided that foreign ownership in the condominium project does not exceed 40% of the total units. This limit is strictly enforced at the title level. Once the cap is reached, additional units cannot be transferred to foreign buyers—even if contracts are signed or payments are completed. Ownership is perfected only upon issuance and transfer of a valid Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT).

What if the property title is lost?

A lost title does not eliminate ownership, but it halts any sale or transfer until legally replaced.

The registered owner must file a petition for reissuance of title—typically through the Register of Deeds and, in some cases, the courts. This process involves public notices, affidavits, and waiting periods designed to prevent fraud. It can take several months or longer, depending on complexity.

Buyers should never proceed with a transaction based on a promise that a lost title will be replaced later. Without a reissued title, ownership cannot be transferred.

Why do some condominiums still not have individual titles?

Condominium titles are often delayed due to developer-side compliance issues, including:

- Unpaid taxes or fees

- Incomplete project documentation

- Unregistered Master Deed or Declaration of Restrictions

- Outstanding obligations with government agencies

Until these are resolved, individual CCTs cannot be issued, even if the buyer has fully paid and taken possession. This is why possession of a unit does not automatically mean legal ownership. Buyers should verify a developer’s title track record before purchasing.

How long does title transfer really take?

In ideal conditions, a clean transfer can be completed in 3 to 6 months.

In reality, timelines frequently extend to 12 months or more due to:

- BIR processing delays

- Registry of Deeds backlogs

- Errors in documents or tax records

- Missing clearances or unpaid taxes

Buyers who plan around optimistic timelines often face frustration. Those who plan for delays protect their capital and their expectations.

Understanding these realities does not complicate the buying process—it prevents irreversible mistakes.

Key Takeaways Buyers Must Remember

Titles protect wealth—or destroy it.

In Philippine real estate, ownership is not emotional, visual, or contractual. It is documentary. A property may look secure, but only a valid and verifiable title gives you enforceable rights. Everything else—possession, payment, promises—is secondary.

Verification is non-negotiable.

Every major loss story shares the same root cause: assumptions replaced verification. A Certified True Copy, annotation review, authority checks, and tax clearances are not optional steps. They are the minimum standard for any serious buyer. Skip one, and the entire transaction is exposed.

Professional guidance is leverage, not cost.

Licensed brokers and real estate lawyers do not slow deals down—they prevent irreversible errors. The fee you hesitate to pay is often the fee that saves you from years of litigation or total loss. In real estate, expertise is not overhead. It is protection.

“This is why experienced brokers and real estate lawyers refuse to proceed with transactions where title issues remain unresolved.”

Buy with clarity. Verify with discipline. Treat the title as the asset—because legally, it is.

Protect Your Investment Before You Sign Anything

Before you sign a contract.

Before you send a reservation fee.

Before you wire funds you worked years to earn—verify the title.

Most real estate losses in the Philippines are not caused by bad intentions. They are caused by insufficient due diligence. This is where disciplined buyers separate themselves from unlucky ones.

If you want:

- A professional review of property titles and ownership documents

- Guided due diligence before committing to a purchase

- Access to verified property listings screened for title and ownership risks

Get expert support before the deal moves forward.

At UPropertyPH, we help buyers, investors, and OFWs evaluate properties with clarity—not assumptions.

“Our review process mirrors the same due diligence standards used in bank-financed and legally vetted transactions.”

Titles are checked. Risks are flagged. Decisions are made with full visibility.

Do not buy on trust. Buy on records.

Protect your capital. Protect your future.

Verify Before You Buy — Get Expert Property Due Diligence

Real estate losses don’t happen because buyers are careless.

They happen because verification is skipped or delayed.

Get professional support before you sign, pay, or commit—so decisions are made on records, not assumptions.

Leave a reply to 23 Must-Know Real Estate Terminologies in the Philippines for Effective Property Buying – U-Property PH Cancel reply