A mortgage in the Philippines is a long-term housing loan secured by property, used to spread the cost of ownership across 10 to 30 years while managing risk between borrower and lender.

You can be earning well, saving consistently, and still make a bad mortgage decision. That is not a contradiction—it is the Philippine property market in practice.

In the Philippine housing loan market, mortgages confuse even financially capable buyers because approval is often mistaken for safety. A bank saying “yes” does not mean the loan fits your life, your risk tolerance, or your long-term plans. It only means you passed their minimum thresholds. Banks protect their balance sheets. You protect your future.

Here is the critical distinction most buyers miss: “bank-approved” is not the same as “financially safe.”

A loan can be approved and still quietly stretch your cash flow, limit your mobility, or trap you in a property that becomes difficult to sell or refinance later. Monthly amortization looks manageable on paper—until repricing hits, expenses pile up, or life changes.

This guide exists to close that gap.

You will not find generic explanations or sales-driven advice here. Instead, this guide will help you:

- Understand how mortgages actually work in the Philippine setting, not just in theory

- Identify whether a loan structure supports or undermines your financial stability

- Avoid common traps that first-time buyers, OFWs, and even investors repeatedly fall into

- Decide with clarity before you sign contracts that lock you in for 20 to 30 years

Think of this as a decision framework, not a sales pitch. By the end, you should be able to look at any mortgage offer and answer one question confidently: Does this loan work for me—or only for the bank?

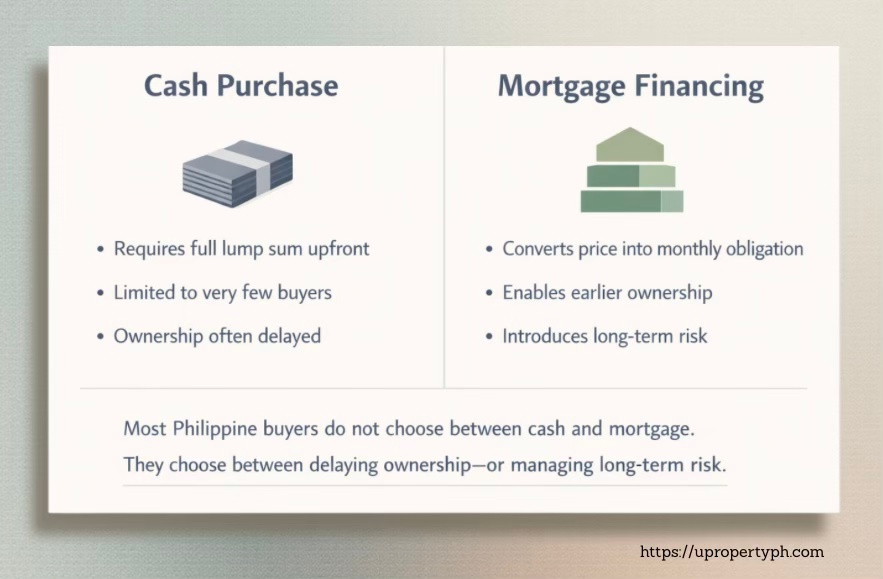

A comparison of cash purchase and mortgage financing in the Philippines, highlighting key differences in ownership timelines and risks.

Why Mortgages Matter in the Philippine Real Estate Market

In the Philippine real estate market, mortgages matter because property prices significantly exceed average household incomes, making financing the primary path to ownership.

Cash buyers get attention, but they are not the market. In the Philippines, they are the exception. Most legitimate end-users—young professionals, growing families, OFWs returning home—rely on mortgages because property prices have outpaced income growth for more than a decade. Waiting to buy in full cash is not conservative; for most households, it is simply unrealistic.

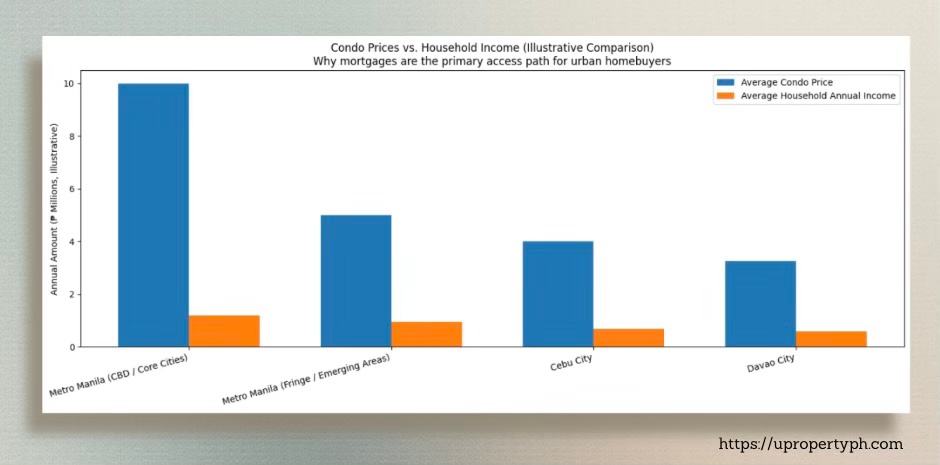

Graph comparing condo prices to household income across major Philippine cities, highlighting financial accessibility for urban homebuyers.

The gap is clearest in Metro Manila. Condo prices in core business districts such as Makati, BGC, Ortigas, and emerging Quezon City nodes are now multiple times higher than the annual income of an average Filipino household. Even dual-income families with stable careers face a simple math problem: without financing, ownership is delayed indefinitely. Mortgages bridge that gap by converting an impossible lump sum into a structured, time-bound obligation.

That does not mean mortgages are shortcuts. They are access tools—nothing more, nothing less.

Used correctly, they allow buyers to secure a home or investment earlier in life while income is still growing. Used poorly, they compress financial flexibility, magnify risk, and create long-term stress masked by “affordable” monthly payments.

This distinction matters. A mortgage should expand options, not narrow them. It should support housing stability or a clear investment thesis, not serve as permission to overbuy. In the Philippine market—where interest rates reprice, traffic reshapes livability, and resale liquidity varies sharply by location—financing decisions have consequences far beyond approval day.

Understanding why mortgages matter is not about justifying debt. It is about recognizing reality: property ownership at today’s prices is largely a financed decision. The real question is not whether to use a mortgage, but how to use one without compromising your financial future.

What a Mortgage Really Is (Philippine Context)

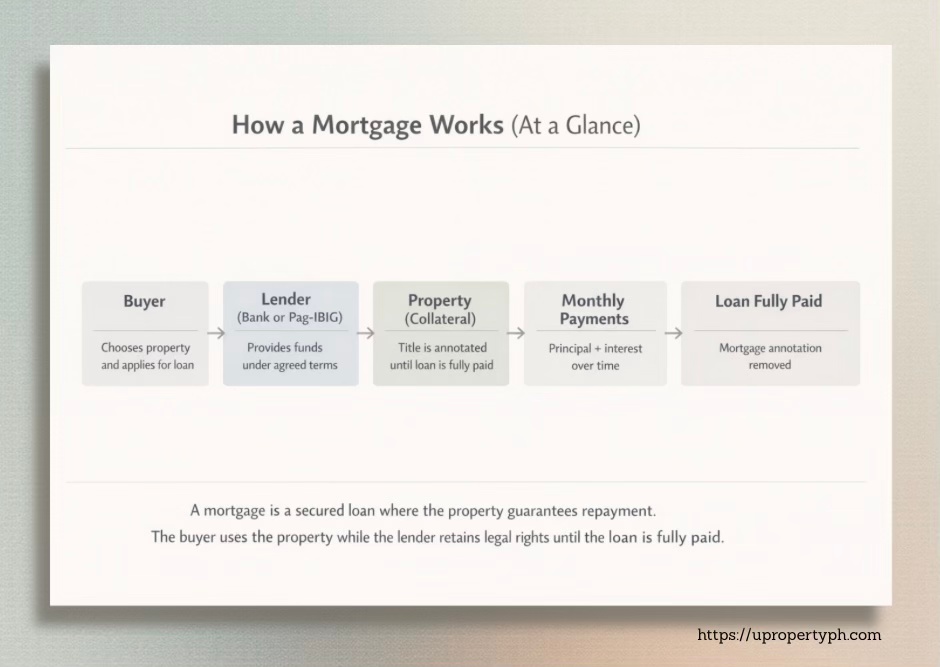

A mortgage is a secured housing loan where the property title serves as collateral until the loan is fully repaid.

At its core, a mortgage is simple: it is a long-term loan used to buy property, making it the most common form of property financing in the Philippines. You receive funds to purchase a house or condominium, and in exchange, the bank places a legal claim on that property until the loan is fully paid. Miss payments long enough, and the lender has the right to recover its money by taking and selling the property.

Flowchart illustrating the mortgage process from buyer to loan approval.

That simplicity is often lost because mortgages are frequently lumped together with other forms of borrowing. They should not be.

A mortgage is fundamentally different from a personal loan. Personal loans are unsecured, shorter-term, and carry much higher interest rates because the bank has nothing to fall back on if you default. Mortgages, by contrast, are secured by real estate, which is why they offer longer terms—often up to 20 or 30 years—and lower interest rates. The trade-off is commitment: once you sign, walking away is neither quick nor cheap.

Mortgages also differ sharply from in-house developer financing, which is common in the Philippine market. In-house financing is not a mortgage in the traditional banking sense. It is a private payment arrangement with the developer, usually offered when bank or Pag-IBIG approval is not yet possible. While it may feel more convenient upfront, it often comes with higher interest rates, shorter terms, and less flexibility. Many buyers underestimate how expensive in-house financing becomes once amortization begins.

The legal anchor of all this is collateral. In Philippine mortgages, the property is annotated as mortgaged on the title. This protects the lender, not the borrower.

The bank’s primary concern is not whether the unit fits your lifestyle or investment goals, but whether the property can be resold at a reasonable value if you default. That is why banks conduct independent appraisals and frequently value properties lower than the agreed selling price.

This leads to a critical reality: banks set conservative rules because they carry downside risk, not because they want to help you buy more.

Loan-to-value limits, age caps, income stress tests, and repricing structures are all designed to protect the lender first. Approval means you meet their minimum risk standards—not that the loan is optimal for you.

Understanding what a mortgage really is shifts your mindset. It is not a favor from a bank, nor a signal that a property is affordable. It is a risk-managed transaction where you must decide how much of that risk you are willing—and able—to carry for decades.

Common mortgage myths in the Philippines worth discarding immediately:

- “If the bank approved it, I can afford it.”

- “Lower monthly payment means safer loan.”

- “In-house financing is cheaper because it’s easier.”

- “I’ll just refinance later if rates go up.”

Each of these assumptions fails in real-world scenarios. This guide will show you why—and how to think more clearly before committing.

How Mortgages Work Step-by-Step

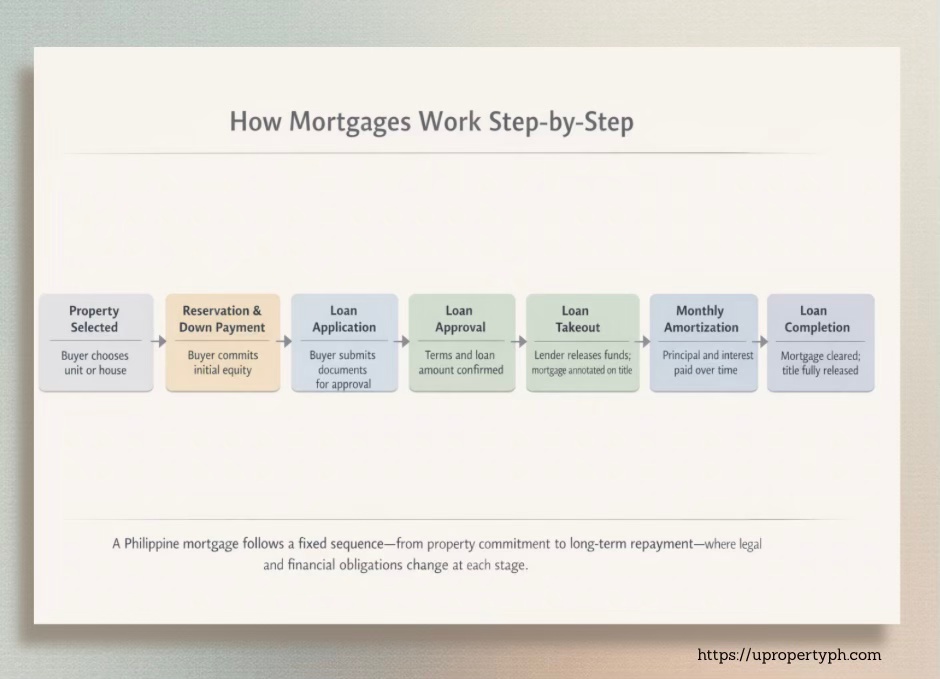

The mortgage process in the Philippines follows a standard sequence, from reservation and down payment to loan takeout and long-term amortization.

Mortgages feel complex because buyers usually encounter them mid-transaction—already committed emotionally and financially. In reality, the process follows a predictable sequence. Once you understand the mechanics, the confusion drops away.

A visual guide outlining the step-by-step process of obtaining a mortgage in the Philippines.

The journey typically starts with the reservation fee. This secures the property and temporarily removes it from the market. It is not part of the loan. Think of it as a signal of intent, not ownership.

Next comes the down payment, usually paid over several months for developer units or upfront for resale properties. This portion represents your equity. Banks will not finance 100% of the price. The larger your down payment, the lower your loan exposure—and the lower the bank’s risk.

Only after this does the loan takeout happen. This is where many buyers get surprised. The bank does not hand money to you. Instead, once your loan is approved and all conditions are met, the bank releases funds directly to the seller or developer. At that point, the mortgage is annotated on the property title, and your long-term obligation officially begins.

From there, you enter monthly amortization in the Philippines, where each payment has two components:

- Principal – the portion that reduces your actual loan balance

- Interest – the cost of borrowing the money

In the early years, a larger share of your payment goes to interest. Over time, the balance shifts, and more of your payment goes toward principal. This is normal, but many buyers do not realize how slow equity buildup can be in the first several years of a Philippine home loan.

A bar graph illustrating how mortgage payments are divided between interest and principal over a 30-year loan timeline, highlighting the dominance of interest in the early years.

What changes over time is not just the balance—it is the risk profile.

Most local mortgages use repricing periods rather than fully fixed rates. Your monthly payment can increase after the fixed period ends. Insurance costs may rise. Property taxes adjust. Life circumstances evolve. A loan that felt comfortable in year one can feel restrictive in year six if you did not plan with margin.

Understanding this timeline reframes the decision. A mortgage is not a static monthly bill. It is a long-duration financial structure with moving parts. The smarter you are at the beginning, the fewer unpleasant surprises you face later.

Types of Home Loans Available in the Philippines

Home loans in the Philippines generally fall into three categories: bank housing loans, Pag-IBIG housing loans, and in-house developer financing.

Not all home loans behave the same way, even if the monthly payment looks similar at the start. In the Philippine market, buyers usually choose among three financing paths. Each serves a purpose. Each carries trade-offs—especially when choosing between a Pag-IBIG vs bank housing loan. The mistake is choosing based on convenience instead of structure.

Bank Housing Loans

Bank housing loans are the most common form of long-term property financing for salaried professionals, business owners with stable income, and established OFWs.

The typical structure includes a fixed-rate period—often 1, 3, or 5 years—followed by a repricing period where the interest rate resets based on prevailing market conditions. This means your loan is not truly fixed for its entire life. What you are locking in is temporary certainty, not permanent cost control.

Banks favor borrowers who present low risk. Stable employment, consistent income history, clean credit records, and reasonable debt-to-income ratios matter more than ambition. Banks also favor properties that are easy to resell: well-located condos, established subdivisions, and developments with strong track records. If either the borrower or the property introduces uncertainty, expect stricter terms or lower loanable amounts.

Bank loans work best when you value structure, longer terms, and relatively lower interest rates—and when you can absorb future repricing without stress.

Pag-IBIG Housing Loans

Pag-IBIG housing loans exist to expand access to homeownership, particularly for Filipino workers who may not meet commercial bank criteria. For many buyers, Pag-IBIG is not a second-tier option—it is the right one.

Its key strengths are longer allowable terms, generally lower interest rates, and more flexible eligibility, especially for lower to middle-income earners. Monthly amortizations are often more forgiving, making Pag-IBIG attractive for first-time buyers and households prioritizing stability over speed.

The limitations are structural. Loan processing is slower. Property and developer accreditation requirements are stricter. Loanable amounts are capped, which can restrict options in higher-priced Metro Manila markets. Pag-IBIG works best when the property price aligns with its limits and when buyers are not under time pressure.

Pag-IBIG becomes the better option when affordability and predictability matter more than speed or premium location.

In-house Developer Financing

In-house financing is frequently misunderstood. It is not a mortgage in the traditional sense. It is a private installment arrangement offered by developers, often marketed as “easier approval” or “no bank requirements.”

This option works in limited scenarios: during early pre-selling stages, for short-term bridging, or when a buyer is temporarily ineligible for bank or Pag-IBIG loans. It can also help buyers secure a unit while preparing documents for eventual bank takeout.

Where in-house financing quietly costs more is in interest rates, shorter terms, and compounding risk. Monthly payments can escalate quickly, and refinancing later is not guaranteed. Many buyers underestimate how expensive staying in-house becomes beyond the initial convenience phase.

In-house financing should be treated as a transitional tool—not a long-term solution.

Home Loan Options in the Philippines: Structural Comparison

Bank vs. Pag-IBIG vs. In-House Financing

| Factor | Bank Housing Loan | Pag-IBIG Housing Loan | In-House Financing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Interest Level | Market-based | Generally lower | Usually higher |

| Loan Term Length | Medium to long | Long | Short to medium |

| Monthly Payment Predictability | Medium | High | Low |

| Approval Strictness | High | Moderate | Low |

| Processing Speed | Medium | Slow | Fast |

| Flexibility After Approval | Medium | Slow | Very low |

| Best Fit For | Stable salaried or established borrowers | First-time and affordability-focused buyers | Short-term or bridging situations |

Each financing option solves a different problem. The safest choice is the one aligned with your income stability, time horizon, and risk tolerance—not the one that looks easiest to approve.

Choosing among these options is not about approval odds. It is about alignment. The right loan structure supports your cash flow, timeline, and risk tolerance. The wrong one does the opposite—slowly and expensively.

Interest Rates Explained — The Real Cost of Borrowing

Mortgage interest rates in the Philippines are typically structured with fixed-rate periods followed by repricing based on market conditions.

Interest rates are where most mortgage mistakes hide. Not because buyers ignore them, but because they misunderstand what they are actually agreeing to.

In the Philippines, most home loans are not fully fixed. What banks offer is a fixed-rate period, usually 1, 3, or 5 years, followed by a repricing period— commonly referred to as mortgage interest repricing in the Philiipines—where the interest rate resets based on market conditions. During the fixed period, your monthly payment feels predictable. After that, it becomes conditional. The longer your loan term, the more repricing cycles you will face.

This is why a “low monthly amortization” can be misleading.

It often reflects a long loan term, a short fixed period, or both. On paper, the payment looks comfortable. In practice, it leaves little room for rate increases, income disruption, or life changes. Many borrowers only realize this when their loan resets and the amortization jumps—sometimes sharply.

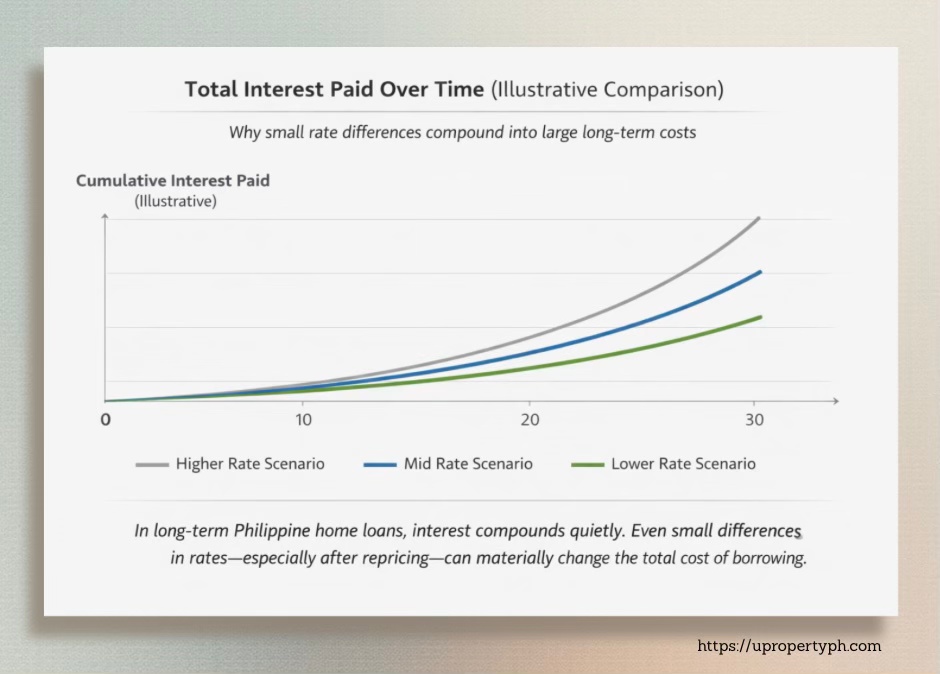

Small rate differences matter more than most people expect. A one-percent increase on a 20- or 30-year loan does not sound dramatic, but over time it compounds into a substantial cost.

In long-term Philippine home loans, interest compounds quietly. Even small differences in rates—especially after repricing—can materially change the total cost of borrowing

You are not just paying more per month; you are paying interest on interest across decades. This is why two buyers with similar properties can end up with vastly different total loan costs.

Understanding this shifts the decision from “Can I afford the payment today?” to “Can I afford this loan across multiple economic cycles?” That is the correct question.

See how loan structure and interest rates affect long-term cost—not just monthly payments.

Refinancing can make sense, but it is not a guaranteed escape hatch. It works best when interest rates drop materially, when your property has appreciated enough to improve loan-to-value ratios, or when your income profile has strengthened. Refinancing also comes with fees, reappraisal, and approval risk. It is a strategic move, not a fallback plan.

Treat interest rates as a long-term risk factor, not a promotional headline. The real cost of borrowing is revealed over time, not at approval.

Collateral, Risk, and Foreclosure (What Buyers Rarely Ask About)

In Philippine mortgage contracts, the property serves as collateral, giving lenders the legal right to recover losses through foreclosure if the borrower defaults.

Most buyers focus on approval, interest rates, and monthly payments. Very few stop to ask the uncomfortable but necessary question: what happens if things go wrong? That silence is costly.

In legal terms, collateral means the property is pledged to the lender as security for the loan. In the Philippines, once a mortgage is executed, the title is annotated to reflect the bank’s claim. You retain possession and use of the property, but ownership is no longer absolute until the loan is fully paid. The bank’s rights are embedded in the title itself.

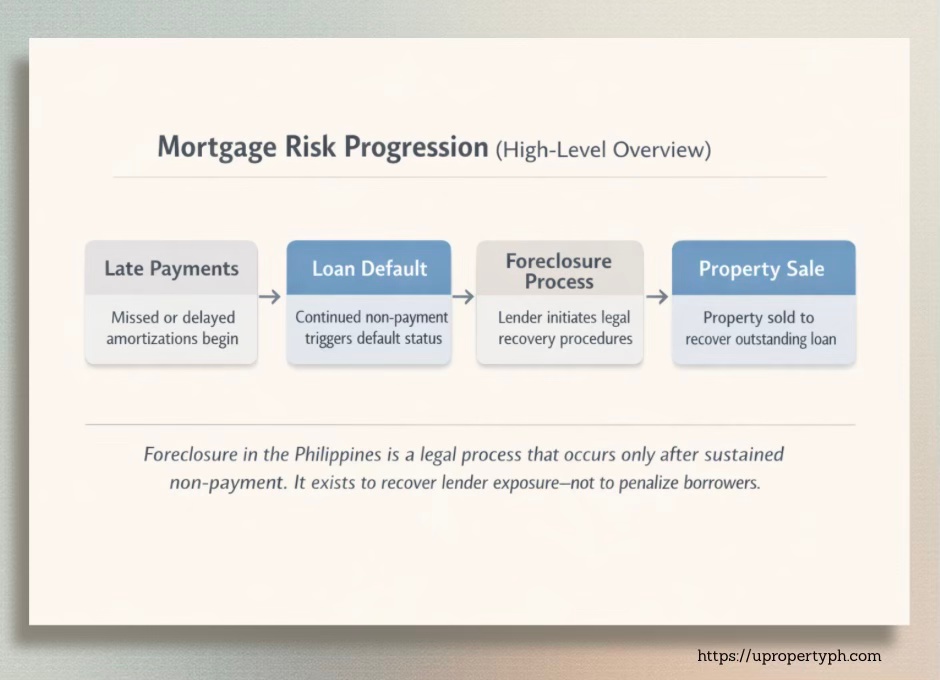

If payments are delayed consistently, the process escalates. Missed amortizations trigger penalties. Continued non-payment can lead to default, and default gives the lender the right to initiate foreclosure.

Most mortgage issues are resolved before reaching foreclosure through restructuring, settlement, or sale.

In Philippine practice, foreclosure is typically judicial or extrajudicial, depending on the mortgage terms. Either path allows the lender to recover its exposure by selling the property, often at a value that prioritizes speed over price.

This is where expectations often clash with reality. Foreclosure is not designed to protect equity or maximize your resale value. It exists to limit the bank’s losses. Any surplus after settling the loan and costs may be returned to the borrower, but counting on that is risky. In distressed sales, prices are usually conservative.

Understanding this explains why banks behave the way they do. Banks care far more about downside risk than upside potential. They do not underwrite based on your optimism, future promotions, or projected rental income. They assess whether the property can be sold quickly and cleanly if you default. That is why appraised values are conservative, loan-to-value ratios are capped, and certain locations or property types receive stricter treatment.

This is not hostility. It is risk management.

For buyers, the takeaway is not fear—it is clarity. A mortgage is a long-term bet on stability: income continuity, health, and market conditions. Respecting the role of collateral forces you to size your loan conservatively and leave margin for uncertainty. That margin is what keeps a temporary setback from becoming a permanent financial problem.

Mortgage Eligibility and Approval Factors

Mortgage eligibility in the Philippines is determined by income stability, debt ratios, borrower profile, age, and credit history.

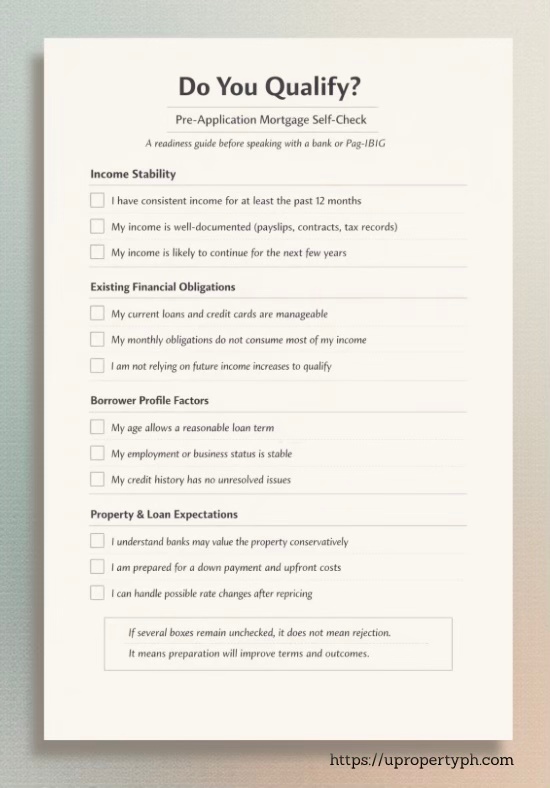

Mortgage approval in the Philippines is not a single decision—it is part of the broader home loan approval process in the Philippines. It is a composite risk assessment. Banks do not ask, “Can this person pay today?” They ask, “Can this person keep paying across decades, under less-than-ideal conditions?” Understanding how that judgment is formed puts you back in control of the process.

If you want help interpreting your readiness, a short financing assessment can clarify your next step.

Income computation and debt ratios come first.

Banks look at gross income, then subtract existing obligations—car loans, credit cards, personal loans, even other mortgages. What remains must comfortably cover the proposed amortization. This is why two buyers earning the same amount can receive very different loan offers. The limiting factor is not income alone; it is available income after debts. A loan that consumes too much of your monthly cash flow signals fragility, not strength.

Your employment profile heavily influences how that income is treated.

- Locally employed borrowers benefit from predictability. Regular payroll, tenure, and employer reputation simplify approval.

- Self-employed borrowers face higher scrutiny. Banks look for consistency through audited financial statements, business permits, and tax filings. Strong income helps, but documentation quality matters just as much.

- OFW borrowers sit in a separate category. Income is often higher, but continuity risk is perceived as greater. Contracts, remittance history, and employer credibility become critical, and some banks apply more conservative terms.

Age limits introduce another trade-off most buyers overlook. Banks cap the borrower’s age at loan maturity, often around 65 to 70. Starting later means shorter allowable terms, which increases monthly payments. Longer terms lower amortization but extend exposure to repricing risk. Neither option is universally better; the right choice depends on where you are in your career and how stable your income trajectory is.

Then there is credit history, which in the Philippines is improving but still uneven. Formal credit records exist, but many borrowers underestimate how small defaults—missed card payments, unpaid utilities, informal obligations—can influence bank perception. Approval is not binary. A weaker credit profile does not always mean rejection, but it often results in lower loanable amounts, shorter fixed periods, or higher rates.

What ties all of this together is pattern recognition. Banks are not judging intent; they are measuring resilience. Preparing before you apply—cleaning up obligations, strengthening documentation, and choosing realistic loan sizes—often matters more than negotiating rates later.

Expert Lens: How I Evaluate Mortgage Risk in the Philippines

When I review a mortgage structure—whether for a first-time buyer or an investor—I focus on four factors, in this order:

- Cash flow resilience: The loan must remain affordable even after interest rate repricing, not just at today’s rate.

- Margin for life changes: I assume income disruptions, not continuous growth. A safe loan leaves room for uncertainty.

- Property exit liquidity: I assess how easily the property can be sold or refinanced while the mortgage is active.

- Worst-case outcome: I ask one blunt question: If things go wrong, is this inconvenience—or financial damage

A mortgage that only works under ideal conditions is not a strategy. It is a gamble disguised as approval.

The Mortgage Application Process (End-to-End)

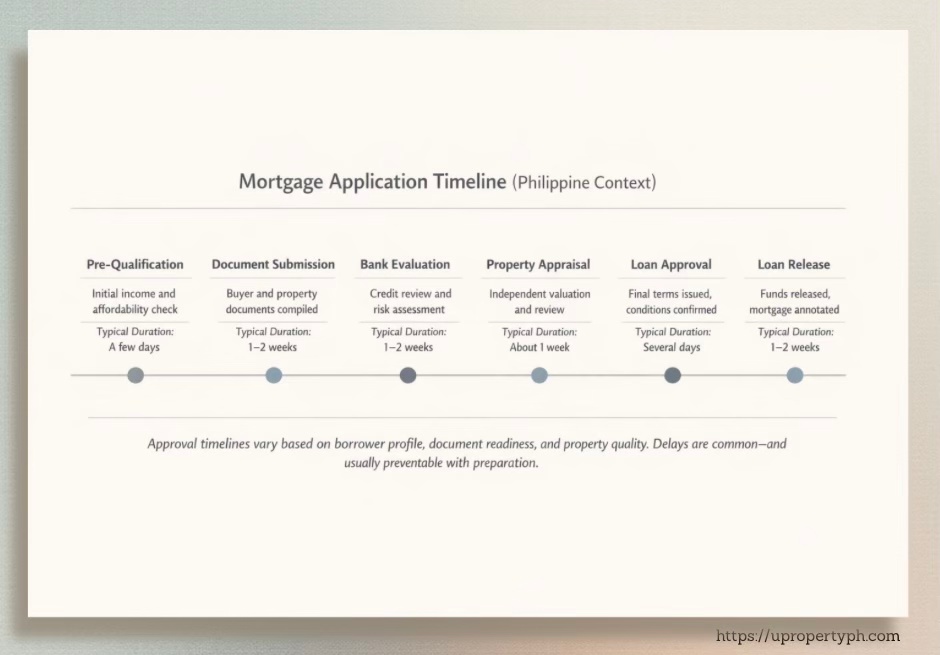

The mortgage application process in the Philippines typically includes pre-qualification, pre-approval, property appraisal, and final loan release.

The housing loan application process in the Philippines feels intimidating because buyers often enter it unprepared and mid-transaction. In practice, it follows a clear sequence. Understanding each stage prevents delays, avoids surprises, and reduces the risk of losing a property you have already committed to.

Applications move fastest when borrower and property documents are complete before submission.

Pre-qualification comes first. This is an informal assessment based on declared income, estimated obligations, and target property price. It answers one question only: Are you in the right range? Pre-qualification is fast, but it is not binding. Treat it as a directional check, not permission to proceed.

Pre-approval is different. This involves document submission and initial credit evaluation. The bank assesses income stability, debt ratios, and borrower profile, then issues a conditional approval. While still subject to property review, pre-approval carries real weight. It strengthens your position with sellers and developers and reduces the risk of last-minute rejection.

Once borrower approval is in place, attention shifts to documentation. On the buyer side, this typically includes proof of income, identification, employment or business records, and credit disclosures. On the property side, banks require clean titles, tax declarations, updated real property tax receipts, and sale documents. Missing or inconsistent paperwork is the most common cause of delays.

The next critical step is property appraisal and bank valuation. Banks do not rely on selling price alone. Independent appraisers assess marketability, condition, location, and resale potential. It is common for bank valuation to come in lower than the agreed price. This is not a mistake; it is risk control. Any gap between selling price and appraised value must be covered by the buyer in cash.

Only after appraisal clearance does the loan move to final approval and release. From application to fund release, realistic timelines range from several weeks to a few months, depending on borrower profile, property type, and document readiness. Rushed applications rarely move faster; organized ones do.

The takeaway is simple: mortgage approval is a process, not a single decision. Buyers who understand the flow—and prepare accordingly—retain leverage and avoid unnecessary stress.

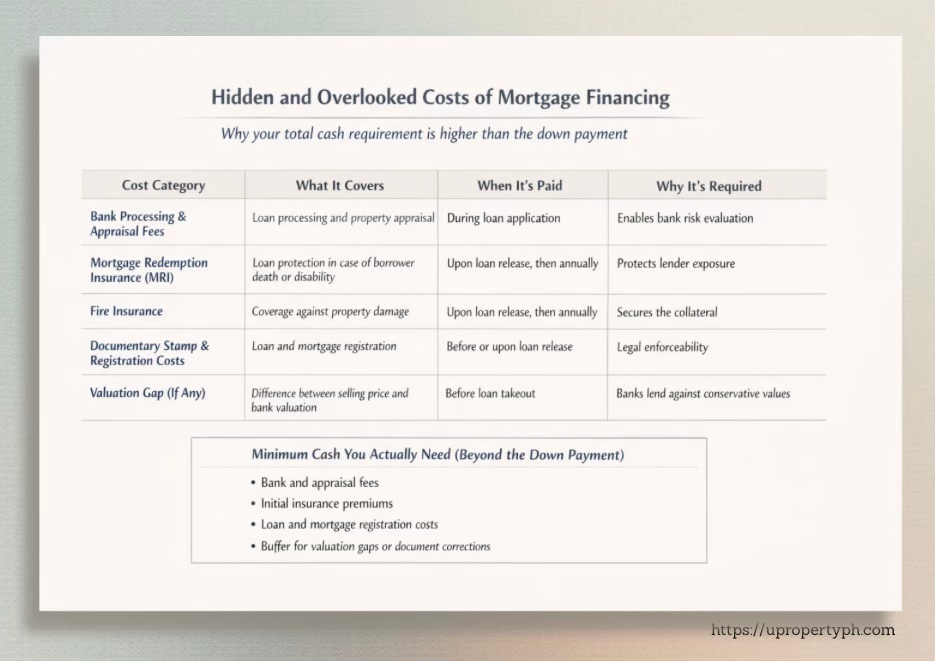

Hidden and Overlooked Costs of Mortgage Financing

Beyond the down payment, mortgage financing in the Philippines includes bank fees, insurance, and registration costs that increase total cash requirements.

Most buyers budget for the down payment and the monthly amortization—and then get blindsided. Mortgage financing in the Philippines carries a layer of ancillary costs that define the true cost of a home loan in the Philippines, which are easy to overlook because they are fragmented, paid at different stages, and rarely emphasized upfront. Ignoring them leads to last-minute cash strain or delayed loan releases.

Planning for these costs early reduces approval delays and stress.

Start with bank fees. These typically include processing fees, appraisal fees, and documentation charges. Individually, they may not look alarming. Combined, they add up. Appraisal alone is non-negotiable, and its cost varies by property type and location. These are paid whether or not the loan pushes through.

Next are insurance requirements, which are mandatory for bank loans.

- Mortgage Redemption Insurance (MRI) protects the lender if the borrower dies or becomes permanently disabled.

- Fire insurance covers the property itself.

These are not optional add-ons. Premiums are often paid annually and increase with loan size. Many buyers only discover this after approval, when the bank presents the final conditions for release.

Then come registration and legal costs. Mortgage registration fees, documentary stamp taxes on the loan, and notarial expenses are required to legally bind the transaction and annotate the mortgage on the title. These are technical necessities, but they are real cash outflows—usually due before funds are released.

Put together, these costs explain a recurring frustration: “I already paid the down payment—why is the bank still asking for cash?”

The answer is that mortgage financing is front-loaded with expenses that sit outside the property price itself.

This is why the total cash needed is almost always higher than expected. Buyers who plan only for the advertised down payment often scramble. Buyers who plan holistically close smoothly.

Minimum Cash You Actually Need (Beyond the Down Payment):

- Bank processing and appraisal fees

- Initial insurance premiums (MRI and fire)

- Loan and mortgage registration costs

- Buffer for valuation gaps or document corrections

Treat this buffer as non-negotiable. It is not padding—it is the cost of making a financed purchase function without friction.

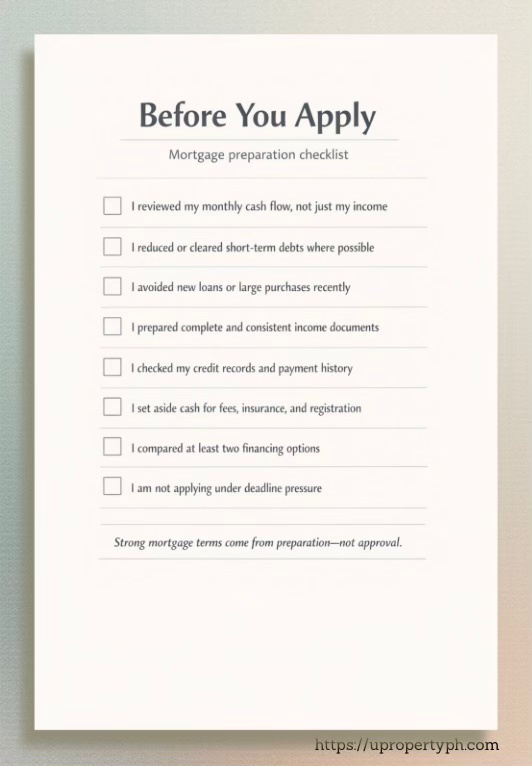

Mortgages for First-Time Homebuyers

For first-time homebuyers in the Philippines, mortgages are often the largest financial commitment they will make, making structure and affordability critical.

First-time buyers rarely fail because they lack discipline. They fail because they underestimate how emotional the first purchase becomes. The excitement of ownership, fear of missing out, and pressure from family or agents can quietly override sound financial judgment.

One common mistake is buying at the edge of approval. Many first-time buyers treat bank approval as a green light to stretch.

The logic is understandable: if the bank says yes, it must be safe. In reality, this leaves no margin for rate repricing, job changes, or unexpected expenses. Another frequent error is focusing entirely on the unit and ignoring the long-term cash flow implications of the loan attached to it.

This leads directly to the second trap: confusing monthly affordability with lifestyle sustainability. A mortgage payment may fit your salary today, but that does not mean it fits your life. Transportation costs, utilities, association dues, insurance, taxes, and basic living expenses all compete for the same income. When the mortgage dominates, lifestyle trade-offs follow—often sooner than expected.

Choosing loan terms responsibly is where first-time buyers regain control. Longer terms lower monthly payments but increase total interest and exposure to repricing risk. Shorter terms build equity faster but demand stronger cash flow discipline. There is no universally correct answer. The right term is the one that leaves breathing room after the mortgage is paid—not the one that maximizes buying power.

A first home should stabilize your life, not constrain it. The goal is not to own as soon as possible at any cost. The goal is to own sustainably.

For first-time buyers, discipline beats ambition. Leave margin. Assume rates will rise. Plan for change. Those who do rarely regret their first purchase.

Download the First-Time Homebuyer Mortgage Readiness Checklist

A practical self-check before committing to a 20–30 year loan

Buying your first home is exciting.

Taking on a mortgage is a long-term financial decision. Taking on a mortgage is a long-term financial decision.

This checklist helps you pause, assess, and decide clearly—before you sign anything.

Inside the checklist, you’ll review:

- Financial readiness beyond the down payment

- Income stability and risk exposure

- Loan structure and repricing awareness

- Lifestyle fit and long-term sustainability

- Decision discipline most first-time buyers skip

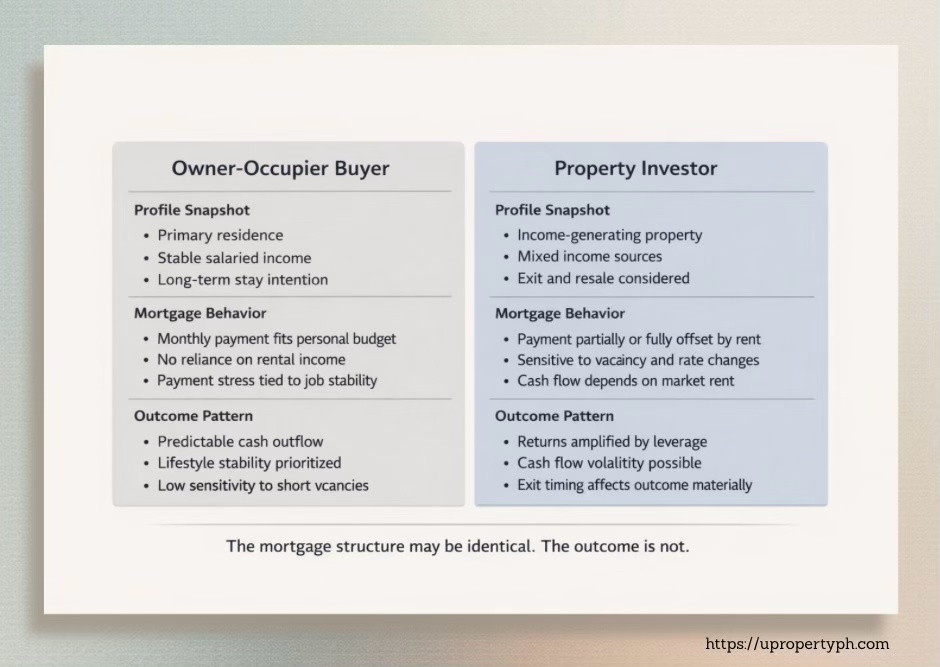

Mortgages for Property Investors

Property investors in the Philippines use mortgages primarily as leverage, balancing loan costs against rental income and long-term value.

For investors, a mortgage is not a path to ownership—it is a leverage tool. Used well, it accelerates portfolio growth. Used carelessly, it destroys cash flow while giving the illusion of progress.

A mortgage that feels safe for an owner-occupier can be fragile for an investor—and vice versa.

The first discipline is using leverage without killing cash flow. A financed investment must survive on its own economics. If the rent cannot materially offset the monthly amortization, the property becomes a liability funded by your salary, not an asset supported by the market. Many first-time investors accept negative cash flow assuming appreciation will rescue the math. That assumption deserves scrutiny.

This brings us to the rent versus amortization mismatch, a common feature of the Philippine condo market. Rental rates are capped by tenant affordability and local supply, while amortization is dictated by interest rates and loan terms. When the gap between rent and amortization is wide, holding costs accumulate quietly. Even modest vacancies amplify the damage.

Investors often justify this gap with appreciation assumptions. Appreciation happens, but it is uneven, cyclical, and location-specific. It is not guaranteed on your timeline. Counting on future price increases to offset weak cash flow turns leverage into speculation. Prudent investors treat appreciation as upside, not the business plan.

The final consideration is exit liquidity while the mortgage is active. A mortgaged property is not as liquid as a fully paid one. Selling requires bank coordination, buyer patience, and pricing discipline. In soft markets, mortgage balances can limit flexibility, forcing sellers to choose between holding longer or accepting discounts.

Successful investors approach mortgages with restraint. They size loans conservatively, stress-test rent assumptions, and plan exits before they buy. The goal is not maximum leverage—it is survivable leverage.

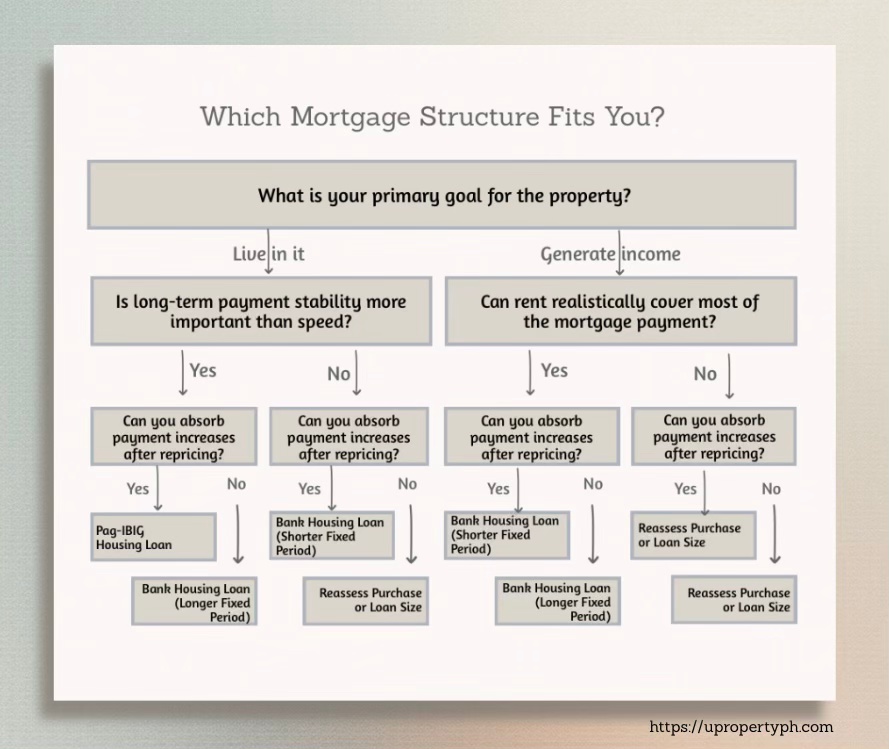

Choosing the Right Financing Strategy

Choosing the right mortgage strategy in the Philippines depends on income profile, risk tolerance, life stage, and long-term plans.

Choosing a mortgage is not about finding the “best” loan or the so-called best mortgage option in the Philippines. It is about choosing the loan that fits your constraints, timeline, and risk tolerance. Most mistakes happen when buyers copy what others did without understanding why it worked—or failed—for them.

If your path leads to “Reassess,” that is a strategic pause—not a failure.

A practical starting point is the bank versus Pag-IBIG decision framework. Bank loans favor borrowers with stable, documented income who want faster processing, higher loan ceilings, and broader property choices. Pag-IBIG favors affordability and longer-term stability, particularly for first-time buyers and households that value predictability over speed. Neither is superior by default. The right choice depends on income profile, property price, and patience for process.

Next is the trade-off between short-term certainty and long-term flexibility. Longer fixed-rate periods offer peace of mind today but often come at a premium. Shorter fixed periods reduce initial cost but increase exposure to repricing sooner. Flexibility also means exit options—prepayment terms, refinancing potential, and the ability to sell without friction. A loan that feels comfortable now but rigid later is rarely a good strategy.

The final and most overlooked element is life stage alignment. Early-career buyers may benefit from conservative loan sizing and longer terms that leave room for mobility. Growing families often prioritize payment stability and location over leverage. Investors require structures that survive vacancies and market shifts. The same loan can be appropriate at one stage of life and reckless at another.

A sound financing strategy accepts that circumstances change. It leaves margin, anticipates repricing, and preserves options. The goal is not to stretch into ownership, but to enter it with resilience.

Realistic Buyer Scenarios (Philippine Setting)

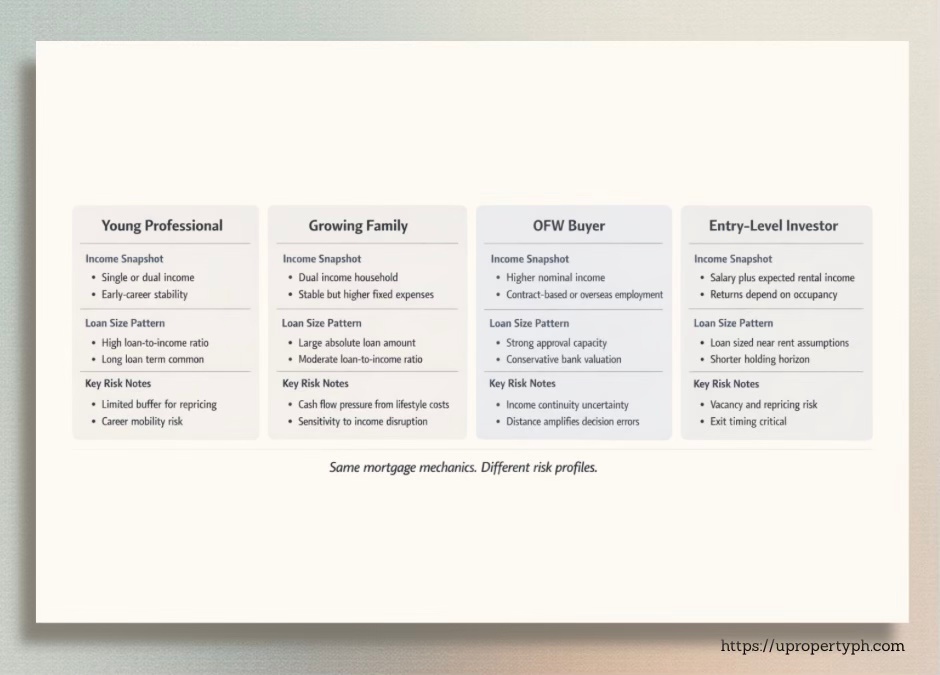

Different borrower profiles in the Philippines experience mortgages differently based on income stability, location, and purpose of purchase.

Abstract advice only goes so far. Mortgage decisions become clearer when viewed through real, familiar situations. The following scenarios reflect patterns that repeatedly appear in Philippine transactions—not outliers, but everyday cases.

A loan that works for one profile may quietly fail for another—even at the same price point.

Young professional buying a first condo

Typically single or newly married, earning steadily but early in their career. The temptation is to maximize buying power and secure a unit in a prime location. The risk lies in locking into a long-term loan with minimal buffer while income is still evolving. The smarter move is often a smaller loan, longer term, and conservative fixed period—prioritizing flexibility over prestige.

Family upgrading to a house and lot

This buyer values space, schools, and stability. Income is usually dual-sourced, but expenses are higher and less flexible. Mortgage success here depends on predictability. Overleveraging to “upgrade” lifestyle can crowd out savings and emergency buffers. Stability beats size. A manageable payment that survives tuition fees and rising household costs is the win.

OFW purchasing remotely

Income may be strong, but continuity risk is real. Contracts end. Markets shift. Banks factor this in, often with stricter terms. The key mistake OFWs make is assuming remittance strength guarantees safety. A conservative loan size, strong documentation, and clear exit plan matter more than maximizing approval. Distance amplifies mistakes.

Entry-level investor using leverage

This buyer is motivated by growth. The risk is optimism. Rental income projections are often generous, vacancies underestimated, and holding costs ignored. A financed investment must survive realistic rent, not best-case scenarios. Leverage should enhance returns, not force dependence on salary support.

These scenarios share one lesson: mortgages amplify both good and bad decisions. Matching loan structure to real-world conditions—not aspirations—determines whether financing becomes a foundation or a constraint.

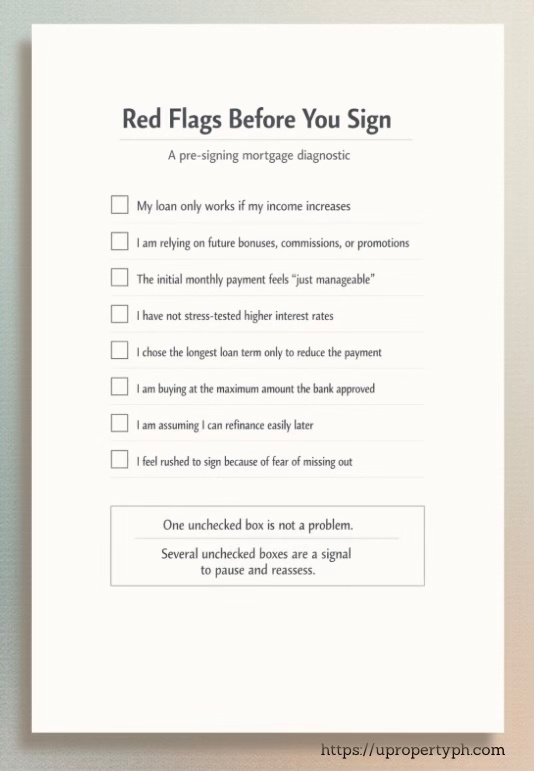

Red Flags That Signal a Bad Mortgage Decision

Certain warning signs indicate when a mortgage decision may be financially risky or unsustainable.

Walking away from a bad structure is often the smartest mortgage decision you can make.

Bad mortgage decisions rarely announce themselves. They are usually framed as optimism, confidence, or “making it work.” Recognizing the warning signs before you sign is what separates durable ownership from long-term regret.

Mortgage Red Flags

- Overreliance on Future Income: Promotions, business growth, or overseas contracts are treated as certainties when they are not. Mortgages are underwritten on what you earn today because tomorrow is unpredictable. If the loan only works assuming income increases, the structure is fragile from day one.

- Ignoring Repricing Exposure: Many buyers fixate on the initial rate and fail to stress-test what happens when the loan resets. If a moderate rate increase breaks your budget, the loan is too large. Repricing is not a remote possibility—it is a built-in feature of Philippine mortgages.

- Stretching Loan Terms Excessively: Lower monthly payments feel safer, but longer terms increase total interest and extend vulnerability to market shifts. Long tenures should create breathing room, not enable overbuying. When a long term is the only way a property becomes “affordable,” that is a warning.

- Buying at the Edge of Approval: Using the maximum loan the bank will offer leaves no margin for error. Approval thresholds are not comfort thresholds. A mortgage should fit comfortably below the limit, not cling to it.

These red flags do not mean “do not buy.” They mean pause, recalibrate, and reassess. A good mortgage decision is quiet. It holds up even when conditions change.

Practical Tips to Secure Better Mortgage Terms

Borrowers can improve mortgage terms in the Philippines through preparation, timing, and informed negotiation.

Borrowers who prepare early negotiate from clarity—not desperation.L

Better mortgage terms are rarely the result of luck. They are the result of preparation, timing, and disciplined negotiation. Borrowers who approach financing strategically are consistently offered more favorable structures than those who apply reactively.

Preparing before you apply is the highest-impact move. Clean up outstanding obligations, even small ones. Reduce credit card balances. Avoid taking new loans in the months leading up to application. For self-employed borrowers, ensure tax filings and financial statements are consistent and defensible. Banks reward clarity and stability. The cleaner your profile, the more leverage you have in structuring terms.

Timing also matters more than most buyers realize. Interest rate environments shift, but so do bank appetites. Some periods favor aggressive lending, others caution. Applying when you are not rushed—before reservation deadlines or construction turnovers—gives you negotiating room. Urgency weakens your position. Preparedness strengthens it.

When discussing offers, focus on negotiating fixed periods, not just headline rates. A slightly higher rate with a longer fixed period can be safer than a cheaper short-term teaser that reprices quickly. Ask how repricing is calculated, what caps exist, and how past resets have behaved. These details matter more than decimals on a quote sheet.

Finally, use professionals strategically. Mortgage brokers, experienced real estate practitioners, and bank relationship managers understand internal policies and timing windows that are invisible to first-time applicants. Their value is not speed—it is alignment. They help match borrower profiles to the right lenders and structures, reducing friction and improving outcomes.

Strong mortgage terms are not given; they are engineered. The more intentional you are before you apply, the fewer compromises you accept after approval.

Key Takeaways and Smart Next Steps

Making a sound mortgage decision in the Philippines requires strategic thinking, not emotional commitment.

A mortgage is not a milestone. It is a long-term strategy expressed in monthly payments. Treated emotionally, it enables overbuying, overconfidence, and long-term stress. Treated strategically, it becomes a disciplined tool that supports housing stability, lifestyle goals, or investment plans without eroding financial freedom.

The most reliable decisions are made when financing is aligned with long-term plans, not short-term excitement. That means sizing loans conservatively, planning for repricing, and accepting that flexibility has value—even if it limits what you can buy today. The best mortgage is the one that still works when conditions change.

There are moments when the smartest move is not to proceed.

If approval pushes you to the edge of affordability, if the structure depends on income growth you do not control, or if the property only works under ideal assumptions, pause and reassess. Walking away early is far cheaper than correcting a bad decision later.

When uncertainty remains, seek advice—not validation. A neutral financing review, second opinion, or structured assessment often surfaces risks you cannot see when you are emotionally invested. Clarity compounds. So do mistakes.

FAQ:

Mortgages in the Philippines

Neither is universally better. Pag-IBIG housing loans prioritize affordability, longer terms, and accessibility, making them suitable for many first-time buyers. Bank housing loans offer higher loan limits, faster processing, and broader property options but apply stricter approval standards. The better choice depends on income profile, property price, and tolerance for repricing risk.

Yes. Refinancing is possible when interest rates improve, your income profile strengthens, or your property value increases. However, refinancing involves appraisal fees, registration costs, and approval risk. It should be treated as a strategic decision, not a guaranteed fallback.

There is no fixed income threshold. Banks and Pag-IBIG assess income relative to existing debts, loan size, borrower age, and loan term. What matters is not gross income alone, but whether the proposed monthly amortization fits comfortably within your cash flow.

Long-term mortgages reduce monthly payments but increase total interest paid and exposure to interest rate repricing. They are not inherently risky if sized conservatively and aligned with stable income, but they become risky when used to stretch affordability.

Late payments incur penalties. Prolonged non-payment can lead to default and eventual foreclosure, depending on loan terms. Early communication with the lender matters. Most serious problems arise when borrowers delay action, not from a single missed payment.

Next steps you can take now:

- Request a financing assessment to stress-test a specific property or loan offer

- Review your mortgage structure before signing any binding documents

Leave a reply to 23 Must-Know Real Estate Terminologies in the Philippines for Effective Property Buying – U-Property PH Cancel reply