Property tax rarely causes problems at the beginning of a real estate journey. It waits quietly in the background—until the exact moment you try to sell, transfer, inherit, or finance a property. That is when unpaid or misunderstood real property tax (RPT) stops being a routine obligation and becomes a deal-breaker.

In the Philippines, property tax issues are one of the most common reasons transactions stall at the last mile. A buyer is ready, financing is approved, contracts are signed—then the process halts because several years of real property tax remain unpaid, receipts are missing, or the tax declaration no longer matches the title. Because of this, the title transfers cannot proceed. Banks will then refuse to release loan proceeds that can cause estate settlements to drag on for years. What should have been a straightforward transaction turns into a costly delay.

This guide is written for:

- Homeowners who want certainty and clean ownership records

- Buyers who want to avoid inheriting someone else’s tax problem

- Investors and landlords who need predictable operating costs and protected ROI

- Property sellers and heirs who want transactions to move without last-minute surprises

By the end of this guide, you will gain three things that matter in real estate:

- Predictability — you will understand how property tax is assessed, computed, and scheduled

- Control — you will know how to prevent penalties, delays, and compliance gaps

- Lower transaction risk — you will spot issues early, before they block a sale, transfer, or loan

Paying property tax regularly removes friction from ownership and protects the liquidity of your asset. Owners who understand this can transact faster while those who ignore it pay later—often at the worst possible time.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Is Real Property Tax (RPT) in the Philippines?

- What Properties Are Subject to Property Tax

- How Property Value Is Determined (And Why Owners Get Confused)

- How Property Tax Is Computed: Step-by-Step

- When and How to Pay Property Tax

- Penalties, Interest, and Consequences of Non-Payment

- Appealing an Assessment or Correcting Errors

- Property Tax in Buying, Selling, and Title Transfers

- Property Tax from an Investor and Landlord Perspective

- Common Myths and Costly Property Tax Mistakes

- Practical Tools and Checklists

- Why Property Tax Compliance Protects Property Value

- Conclusion

What Is Real Property Tax (RPT) in the Philippines?

Real Property Tax (RPT) is an annual tax imposed on the ownership of real property in the Philippines. It applies whether the property is used, rented out, vacant, or generating income. The obligation exists simply because you own the asset.

At its core, RPT is an ownership tax. You do not wait for a sale, a transfer, or a profit before it applies. The moment a property is registered under your name and declared for taxation, RPT accrues every year.

Legal Basis: Why RPT Exists

The authority to assess and collect real property tax comes from the Local Government Code of 1991 (Republic Act No. 7160). This law decentralizes taxation powers and allows local government units (LGUs)—cities, municipalities, and provinces—to fund local services through property taxes.

This is why:

- RPT rates vary by location

- Assessment values differ between cities

- Payment rules and discounts are LGU-specific

Property tax is designed to fund local infrastructure and services such as roads, public schools, health facilities, disaster response, and community development. In practical terms, RPT is the price of maintaining the locality where your property sits.

Why RPT Is Paid to LGUs, Not the BIR

A common mistake—especially among first-time buyers—is assuming that all property-related taxes are handled by the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR).

- RPT is paid to the city or municipal treasurer, not the BIR

- The City or Municipal Assessor determines the taxable value

- The Treasurer’s Office collects the tax

The BIR only becomes involved when a transaction occurs (sale, donation, inheritance). RPT exists independently of those events and continues year after year.

RPT vs Other Property-Related Taxes (Know the Difference)

Understanding how RPT differs from other taxes prevents costly assumptions and missed payments.

Real Property Tax (RPT)

- Paid annually

- Triggered by ownership

- Collected by the LGU

- Required even if the property earns nothing

Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

- Paid only when selling a property

- Triggered by a transfer for value

- Collected by the BIR

- Commonly misunderstood as an “income tax”

Documentary Stamp Tax (DST)

- Paid when documents are executed

- Applies to deeds, mortgages, and contracts

- Collected by the BIR

- One-time, transaction-based

Estate Tax

- Paid when property is transferred due to death

- Required before title can be transferred to heirs

- Collected by the BIR

- Does not replace unpaid RPT

Property-Related Taxes in the Philippines: What’s the Difference?

| Tax Type | When It Is Paid | Paid To | Common Misconception |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real Property Tax (RPT) | Paid annually as long as you own the property | City or Municipal Treasurer (LGU) | “I only pay this when I sell or earn income” |

| Capital Gains Tax (CGT) | Paid when selling real property | Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) | “This is a tax on profit or rental income” |

| Documentary Stamp Tax (DST) | Paid when signing deeds or contracts | Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) | “This replaces property tax” |

| Estate Tax | Paid when transferring property due to death | Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) | “Once estate tax is paid, all property taxes are settled” |

The critical takeaway is: RPT does not go away just because another tax was paid. A property can be fully compliant with BIR taxes and still be blocked by unpaid local property taxes.

What Properties Are Subject to Property Tax

If you answered “yes” to most of these questions, your property is almost certainly subject to real property tax.

Legal exemptions are narrow and strictly applied. Assumptions—especially around vacancy, inheritance, or lack of income—are the most common reason property tax problems surface late.

One of the most persistent sources of confusion in Philippine real estate is whether a specific property is actually subject to real property tax. The default rule is: if you own real property, it is taxable—unless a clear legal exemption applies.

Taxable Properties

The following property types are automatically subject to Real Property Tax (RPT) once declared and assessed by the local government unit:

Residential houses and land

This includes single-family homes, townhouses, duplexes, and residential lots—whether owner-occupied, rented out, or vacant. Use does not remove tax liability.

Condominium units

Condo owners pay RPT on their individual units. This is separate from association dues. A frequent mistake is assuming that monthly condo dues already cover property tax—they do not.

Commercial and industrial properties

Office buildings, retail spaces, warehouses, factories, and mixed commercial structures are taxed at higher assessment levels due to income-generating potential.

Agricultural land

Agricultural properties are taxable, although they generally enjoy lower assessment levels. However, misclassification or conversion can significantly change tax exposure.

Special Cases That Still Trigger Property Tax

Certain situations give owners a false sense of exemption. In practice, these properties are still taxable:

Vacant land

A property does not need a structure to be taxed. Vacant land remains subject to RPT and may even be classified as idle land, which can attract higher rates depending on the LGU.

Mixed-use properties

Properties with both residential and commercial use are assessed portion by portion. For example, a ground-floor commercial space with residential units above it will be taxed at different assessment levels.

Properties under usufruct or long-term lease

Even if another party enjoys the right to use the property, the registered owner remains responsible for the tax unless specific contractual arrangements shift the burden (which does not remove LGU collection rights).

Exemptions and Partial Exemptions (Strictly Construed)

Tax exemptions are narrowly interpreted and often misunderstood.

Government-owned properties

Properties owned by the national or local government are generally exempt. However, once leased to private entities for commercial use, tax exposure may arise.

Religious, charitable, and educational institutions

These properties are exempt only if used exclusively for religious, charitable, or educational purposes. Partial commercial use—such as rentals, bookstores, or paid parking—can void the exemption for the affected portion.

The Practical Rule Owners Should Follow

If a property:

- Has a title or tax declaration under your name

- Exists physically or as land

- Is located within an LGU

Assume it is taxable until the assessor confirms otherwise. Relying on assumptions is how back taxes quietly accumulate.

How Property Value Is Determined (And Why Owners Get Confused)

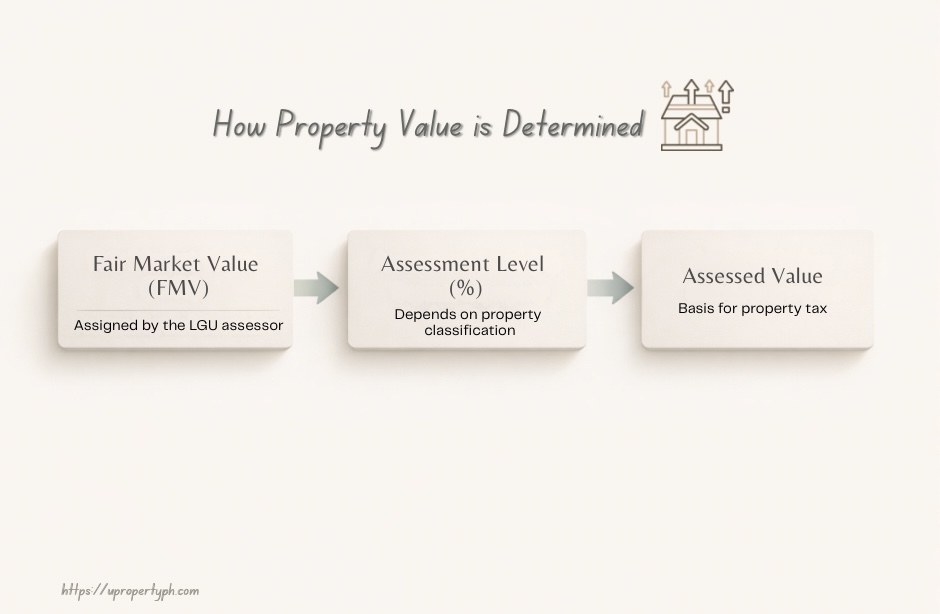

This is why a ₱10M property is never taxed at ₱10M.

Real property tax is not based on market value. It is based on an assessed value derived through a structured process handled by the local government.

The Role of the City or Municipal Assessor

The City or Municipal Assessor’s Office is responsible for determining how much your property is worth for tax purposes. This office:

- Establishes property values based on schedules approved by the LGU

- Classifies properties by use (residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural)

- Applies legally prescribed assessment levels

- Updates values during periodic reassessments

The assessor does not look at your asking price, your purchase price, or online listings. Their valuation follows an LGU-approved framework—not the open market.

Three Terms You Must Understand

Certain situations give owners a false sense of exemption. In practice, these properties are still taxable:

Fair Market Value (FMV)

This is the value assigned to your property by the assessor based on location, land classification, size, improvements, and comparable properties within the LGU’s valuation schedule. FMV is an administrative value—not a selling price.

Assessment Level

This is a percentage applied to the FMV depending on how the property is used. Residential properties are assessed at lower percentages; commercial and industrial properties are assessed higher.

Assessed Value

This is the taxable base. It is calculated as:

Fair Market Value × Assessment Level = Assessed Value

Real property tax is computed from this number—not from FMV and definitely not from market price.

Assessment Levels by Property Classification

Assessment levels vary by LGU but generally follow this structure:

Residential

Lower assessment level (often 10%–20%)

Agricultural

Among the lowest levels

Commercial

Significantly higher

Industrial

Highest assessment levels

| Property Classification | Typical Assessment Level | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Residential | 10% – 20% | Lower rates reflect basic housing use rather than income generation |

| Agricultural | 10% or lower | Encourages land productivity and food security |

| Commercial | 30% – 50% | Higher rates due to income-generating potential |

| Industrial | 50% or higher | Highest assessment due to scale and economic use |

| Special / Mixed-Use | Varies by portion | Each portion is assessed based on actual use |

Assessment levels vary by local government unit and are subject to periodic revision. Always verify current levels with the City or Municipal Assessor.

This system exists to balance tax burden according to income-generating potential.

Why Assessed Value Is Lower Than Market Value

A property selling for ₱10 million in the open market may have:

- An FMV far below ₱10 million based on LGU schedules

- An assessment level that further reduces the taxable base

As a result, the assessed value—and the tax due—are only a fraction of the market price. This is why two similar-looking properties can have very different tax bills depending on classification and location.

General Revision of Assessments: Why Taxes Suddenly Increase

LGUs periodically conduct a general revision of property assessments. When this happens:

- FMVs are updated

- Classifications may change

- Assessed values increase even if the property itself did not change

Many owners mistake this for a new tax or an error. In reality, it reflects an overdue adjustment to align older valuations with current conditions. This is why property taxes can jump after years of stability—without any renovation or sale taking place.

Understanding this process prevents panic and helps owners plan ahead instead of reacting late.

How Property Tax Is Computed: Step-by-Step

Once you understand assessed value, property tax computation becomes mechanical. There are no hidden formulas—only steps that are often never explained clearly. This section removes guesswork and makes your annual real property tax (RPT) predictable.

Sample Property Tax Computation (Illustrative)

| Step | Description | Example Amount (₱) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Fair Market Value (FMV) | Value set by the local assessor | 3,000,000 |

| 2. Assessment Level | Percentage based on property classification | 20% |

| 3. Assessed Value | FMV × Assessment Level | 600,000 |

| 4. Basic RPT | Assessed Value × RPT rate | 12,000 |

| 5. Special Education Fund (SEF) | Additional levy (typically 1%) | 6,000 |

| 6. Total Annual Property Tax | Basic RPT + SEF | 18,000 |

Actual rates and assessment levels vary by local government unit. This example illustrates the computation flow, not a fixed tax amount. This entire computation is based on assessed value—not market price.

Every property tax bill follows this same sequence. Only the numbers change.

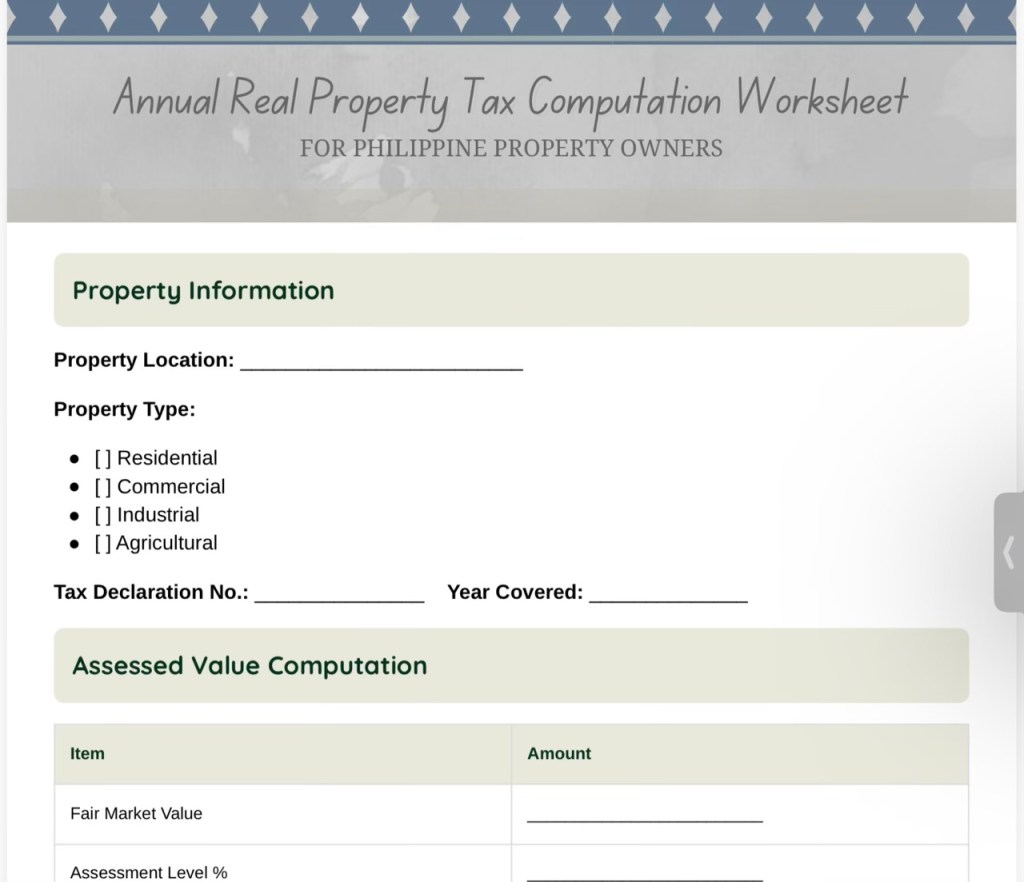

Download: Annual RPT Computation Worksheet

A one-page worksheet you can reuse every year to estimate property tax, track payments, and stay compliant.

Use this worksheet once a year or before buying, selling, or inheriting property to spot tax issues early.

Enter your name and email to download free.

The Basic Property Tax Formula

At its simplest, RPT computation follows this sequence:

Add any applicable levies, and you arrive at your total annual property tax.

This structure applies nationwide. What changes are the rates and add-ons, depending on location and property type.

RPT Rates by LGU Type

The Local Government Code sets maximum rates. LGUs may impose lower rates, but they cannot exceed these caps.

Provinces

up to 1% of assessed value

Cities

up to 2% of assessed value

Metro Manila

up to 2% of assessed value

This is why two identical properties can have different tax bills simply because one is in a city and the other in a province.

Additional Levies You Must Account For

Property tax rarely stops at the basic RPT.

Special Education Fund (SEF)

Most LGUs impose an additional 1% of assessed value earmarked for public education. SEF is mandatory and collected alongside basic RPT.

Idle Land Tax (where applicable)

Vacant or underutilized land may be subject to an idle land tax, depending on LGU ordinances and land classification. This is designed to discourage land banking in urban areas.

Failing to account for these add-ons is how owners underestimate their true annual tax cost.

Sample Computations (Realistic Scenarios)

Example 1: Metro Manila Condominium

- Fair Market Value: ₱3,000,000

- Assessment Level (Residential): 20%

- Assessed Value: ₱600,000

Taxes:

- Basic RPT (2%): ₱12,000

- SEF (1%): ₱6,000

Total Annual RPT: ₱18,000

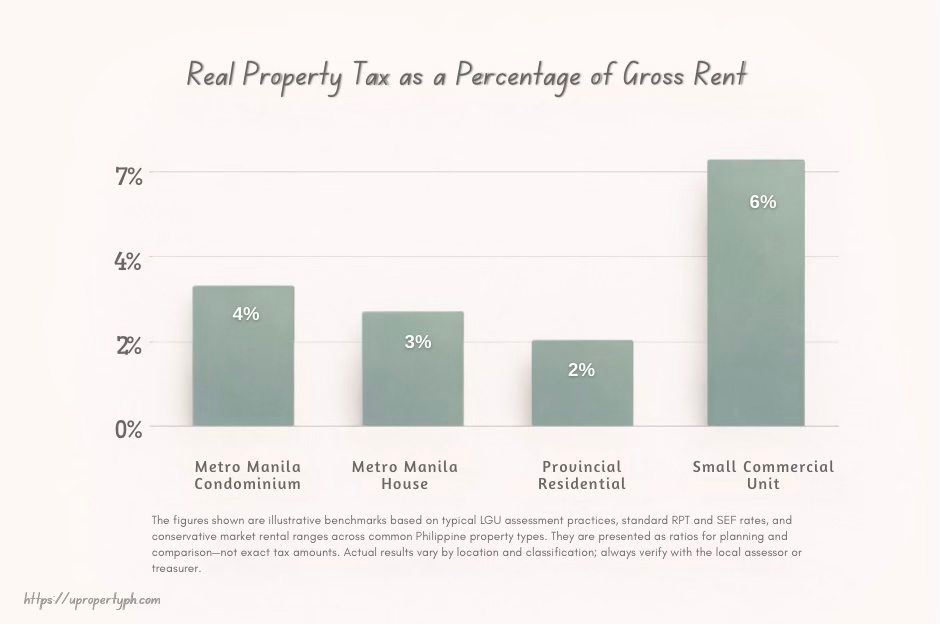

For an investor earning ₱300,000 gross rent annually, this single line item already consumes 6% of gross income—before association dues, maintenance, or vacancies.

Example 2: Provincial House and Lot

- Fair Market Value: ₱2,500,000

- Assessment Level (Residential): 15%

- Assessed Value: ₱375,000

Taxes:

- Basic RPT (1%): ₱3,750

- SEF (1%): ₱3,750

Total Annual RPT: ₱7,500

Lower LGU rates and assessment levels explain why provincial ownership often carries lighter tax burdens.

Example 3: Small Commercial Property

- Fair Market Value: ₱8,000,000

- Assessment Level (Commercial): 50%

- Assessed Value: ₱4,000,000

Taxes:

- Basic RPT (2%): ₱80,000

- SEF (1%): ₱40,000

Total Annual RPT: ₱120,000

This is why property classification matters as much as location. A change from residential to commercial use can dramatically alter tax exposure.

When and How to Pay Property Tax

Most property tax penalties in the Philippines are not caused by inability to pay. They are caused by missed deadlines, forgotten receipts, or unclear payment options. The system is predictable—once you understand the schedule and process.

Choosing a payment method early makes property tax predictable—and avoids penalties altogether.

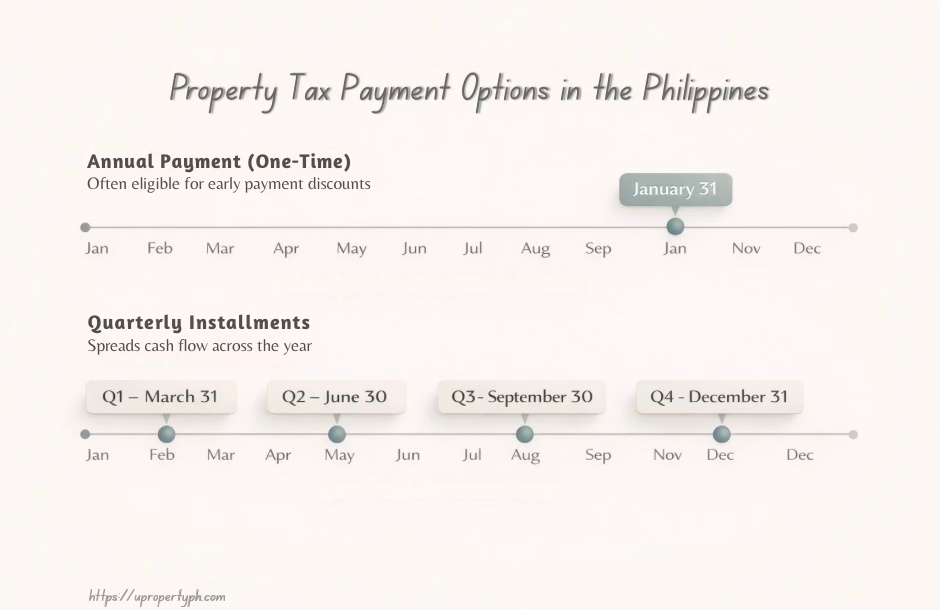

The Annual Property Tax Deadline

The standard deadline for paying real property tax is January 31 of each year. This applies nationwide unless your local government unit (LGU) officially announces a variation.

Paying on or before this date keeps your property in good standing and preserves eligibility for early payment discounts. Missing it immediately exposes you to interest and penalties.

Quarterly Payment Options

Many LGUs allow property owners to pay RPT in four quarterly installments:

- 1st Quarter: on or before March 31

- 2nd Quarter: on or before June 30

- 3rd Quarter: on or before September 30

- 4th Quarter: on or before December 31

Quarterly payments ease cash flow but often forfeit early payment discounts. Owners who can pay annually usually come out ahead.

Early Payment Discounts

To encourage prompt compliance, LGUs typically offer early payment discounts, commonly ranging from 10% to 20% of the basic RPT.

These discounts usually apply only to full annual payments made early in the year. Once the discount window closes, the full tax amount applies—even if you still pay before the deadline.

For multi-property owners, this discount alone can justify early settlement.

Having these ready turns property tax payment into a single, predictable step—not a recurring problem.

Where and How to Pay Property Tax

Property tax payments are handled at the local level, not through the BIR.

City or Municipal Treasurer’s Office

This is the default payment point. Payments can usually be made in person, and official receipts are issued immediately.

Authorized Banks

Some LGUs partner with local or government banks to accept RPT payments. Availability varies by city or municipality.

Online Payment Portals (Select LGUs Only)

A growing number of LGUs offer online payment systems. Coverage is still limited, and systems vary in reliability. Always confirm that digital receipts are recognized by the treasurer’s office.

Regardless of channel, keep all official receipts. Missing receipts are one of the most common causes of transaction delays years later.

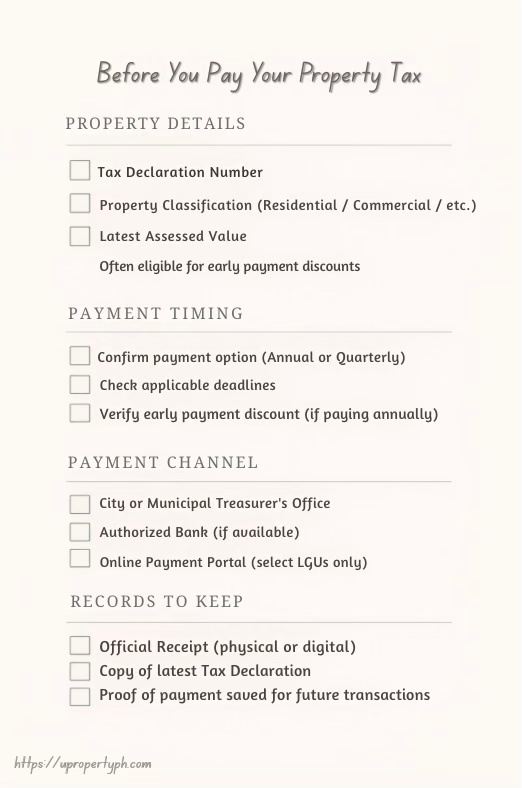

Common Documentary Requirements

Before paying, prepare the following:

- Latest tax declaration number

- Previous RPT official receipts (if available)

- Valid identification (for walk-in payments)

- Authorization letter (if paying on behalf of the owner)

Discrepancies between tax declarations and titles should be corrected early—never at closing.

Penalties, Interest, and Consequences of Non-Payment

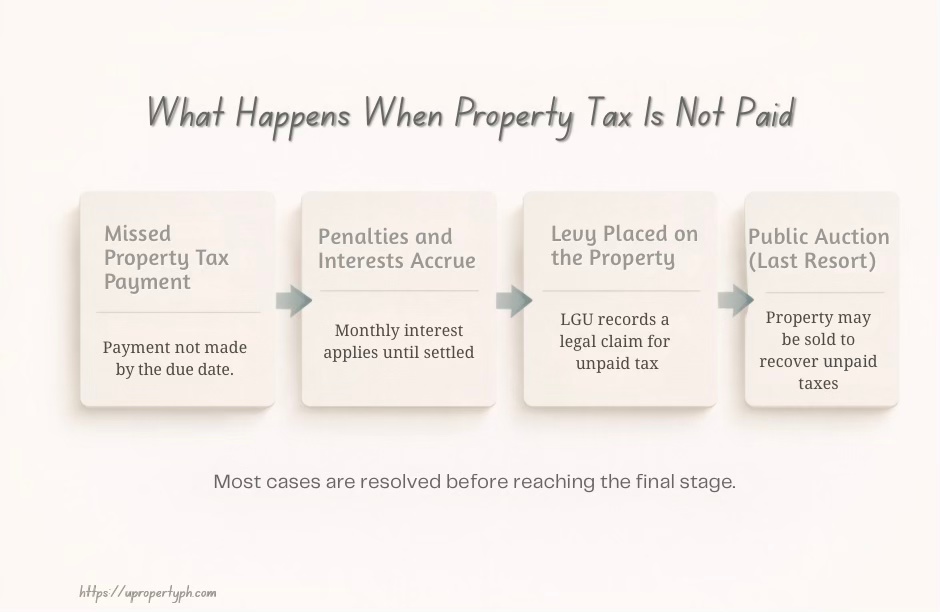

Unpaid real property tax (RPT) does not trigger immediate drama. There are no demand letters on day one, no court summons the next week. That quiet period is exactly why many owners underestimate the risk. By the time consequences surface, they appear all at once—usually when a transaction is already underway.

The goal here is not alarm, but clarity. Once you understand how penalties work and where the process leads, non-payment stops being a gamble.

Interest Rates and Penalty Caps

When RPT is not paid on time, interest accrues monthly. Under the Local Government Code, interest is capped at a maximum annual rate, but the accumulation is still meaningful—especially over multiple years.

Key points owners often miss:

- Interest begins immediately after the due date

- Penalties apply per year of delinquency

- Long-term non-payment can stack years of interest

A single missed year may feel manageable. Five to ten years of delinquency rarely are.

How Penalties Compound Over Time

Property tax penalties compound not because rates are extreme, but because non-payment tends to be ignored. By the time action is taken, the tax obligation has quietly multiplied.

What starts as a modest annual amount often turns into a lump sum that must be paid in fullbefore any transaction can proceed. There is no installment plan when a buyer is already waiting.

From Delinquency to Levy to Auction

The enforcement process follows a defined path:

- Delinquency: The property becomes tax-delinquent after non-payment.

- Levy: The LGU places a legal claim on the property to secure the unpaid tax.

- Public Auction: If delinquency continues, the property may be offered at public auction to recover the taxes due.

This process takes time, which is why many owners feel safe delaying payment. But once initiated, reversing it becomes expensive and procedurally complex.

Most properties are not lost at auction—but many deals collapse long before that stage.

This escalation takes time—but once it starts, it must be resolved before any sale, transfer, or loan can proceed.

Why Unpaid RPT Blocks Real Estate Transactions

This is where non-payment causes the most damage.

Property sales

Buyers, brokers, and lawyers require updated RPT receipts. No receipts, no closing.

Title transfers

Register of Deeds will not process transfers without tax clearance.

Estate settlement

Heirs cannot transfer ownership if years of RPT remain unpaid. This is a common reason inherited properties remain frozen for decades.

Bank financing

Banks will not release loan proceeds on properties with tax delinquencies. Even minor gaps can delay approval.

This is why experienced professionals say: property tax does not punish ownership—it punishes movement. The moment you try to act, unpaid RPT becomes visible.

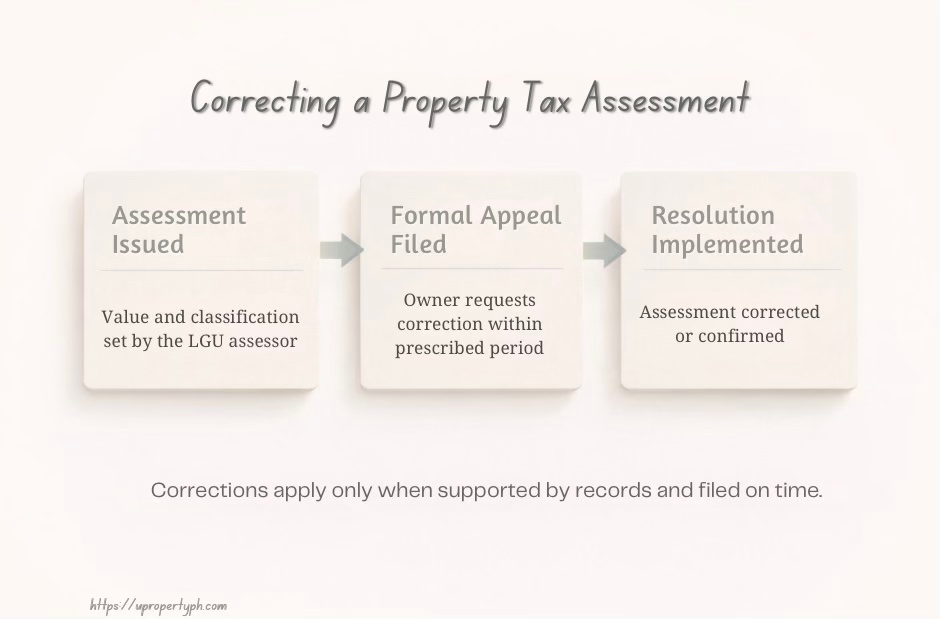

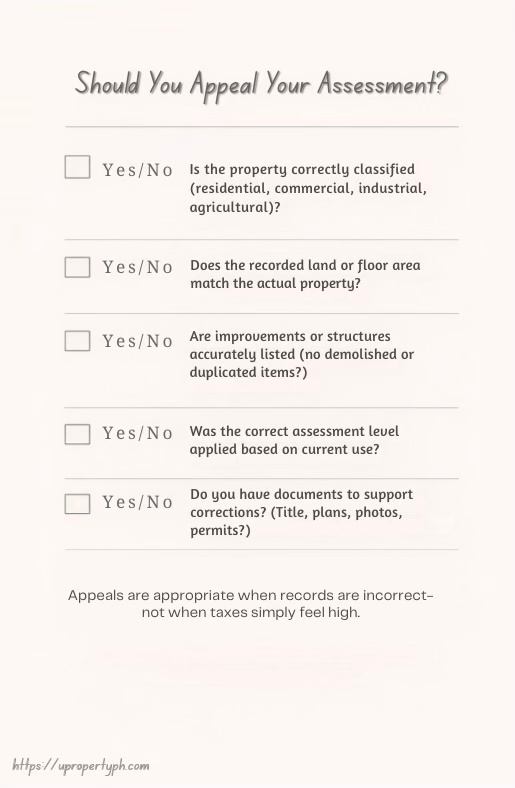

Appealing an Assessment or Correcting Errors

Appealing a property tax assessment is not a loophole for lowering taxes on demand. It is a corrective mechanism designed to fix clear errors. It protects owners from overassessment when used properly. It wastes time and creates false expectations when used casually. This section sets realistic boundaries—so you know when an appeal makes sense and when it does not.

Valid Grounds for Appeal

An appeal is appropriate when there is a verifiable error, not simply because the tax feels high. Common valid grounds include:

- Incorrect property classification (e.g., commercial instead of residential)

- Erroneous land area or floor area

- Overstated or duplicated improvements

- Application of the wrong assessment level

- Clear mismatch between the property and the LGU’s valuation schedule

Market conditions alone—such as a slow market or a low selling price—are not valid grounds.

Appeals are about correcting records—not negotiating tax bills.

Common Errors That Justify Review

Most successful corrections stem from documentation issues rather than valuation disputes.

Misclassification

A residential property incorrectly tagged as commercial can double or triple tax exposure overnight.

Incorrect area measurements

Old tax declarations often carry outdated lot sizes or floor areas, especially after subdivisions or partial transfers.

Improvement discrepancies

Demolished structures still appearing on records, or renovations recorded inaccurately, can inflate assessed value.

These errors persist because tax records are rarely updated unless the owner initiates the correction.

If most answers are “Yes,” an appeal may be worth pursuing. If not, correcting expectations is usually the better move.

The Appeal Process and Timelines

The process generally follows this path:

- Review the assessment with the City or Municipal Assessor’s Office

- File a formal appeal within the prescribed period

- Elevate to the Local Board of Assessment Appeals (LBAA) if unresolved

- Await decision and implementation of any approved correction

Timing matters. Appeals must be filed within specific windows after assessment notices or revisions. Miss the deadline, and the assessment stands for that cycle.

Offices Involved

- City or Municipal Assessor – initial review and correction requests

- Local Board of Assessment Appeals – formal adjudication

- Treasurer’s Office – implements revised tax billing once approved

Coordination between offices takes time. Expect procedural steps, not instant outcomes.

Realistic Expectations on Cost and Duration

This is where non-payment causes the most damage.

Appeals are not free of friction. Expect:

- Several weeks to months for resolution

- Possible professional fees if consultants or lawyers are involved

- Corrections to apply prospectively, not retroactively in many cases

The objective is accuracy, not negotiation. Successful appeals fix errors; they do not guarantee lower taxes if records are already correct.

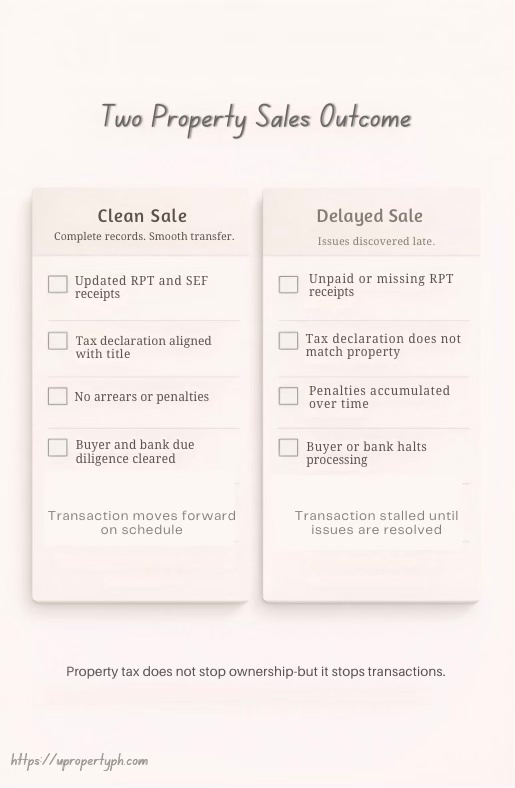

Property Tax in Buying, Selling, and Title Transfers

Real property tax becomes most visible when a property moves. Transactions expose what routine ownership can hide. This is why RPT is a transaction risk variable.

Why Updated RPT Receipts Are Non-Negotiable

Every legitimate transfer in the Philippines requires proof that real property tax is fully paid and current. Updated RPT receipts are demanded by:

- Buyers and their counsel

- Banks and appraisers

- The Register of Deeds

- Estate settlement courts and notaries

No receipts, no progress. Even a single missing year can stop a transfer cold.

Common Deal Delays Caused by Unpaid Taxes

These delays recur across markets and price points:

- Years of unpaid RPT discovered during due diligence

- Missing official receipts that require reissuance

- Tax declarations that do not match the title or actual improvements

- Idle land classifications triggering unexpected assessments

- Heirs discovering delinquency only after a buyer is secured

The cost is not only penalties. Deals fall apart when timelines slip, loan approvals expire, or buyers walk.

The difference is rarely the property. It’s the paperwork.

Buyer Due Diligence Responsibilities

Buyers inherit problems they fail to detect. Due diligence must include:

- Verification of latest RPT receipts (not just “recent”)

- Confirmation of no delinquency or arrears

- Cross-checking tax declaration vs title (area, classification, improvements)

- Ensuring taxes are paid up to the current quarter or year

Treat RPT the same way you treat the title: verify, document, confirm.

Seller Pre-Sale Compliance Checklist

Sellers who prepare early close faster. Before listing:

- Settle all unpaid RPT and SEF

- Secure certified true copies of recent receipts

- Align tax declaration with actual property condition

- Resolve classification issues (residential vs commercial)

- Confirm no idle land exposure

Pre-sale compliance turns RPT from a last-minute obstacle into a non-issue.

Broker Best Practices

Professional brokers do not wait for due diligence to surface tax issues. Best practice includes:

- Requesting RPT documents at listing intake

- Flagging discrepancies before marketing

- Coordinating early with assessors or treasurers

- Educating clients on timing and payment strategy

Brokers who manage RPT proactively protect timelines, credibility, and commissions.

Property Tax from an Investor and Landlord Perspective

For investors and landlords, real property tax (RPT) should never be treated as a surprise expense. It is a recurring, forecastable operating cost—and when managed deliberately, it becomes a line item you control rather than one that erodes returns quietly.

Impact of Property Tax on Rental ROI (Illustrative)

| Metric | RPT Ignored | RPT Accounted For |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly Rent | ₱30,000 | ₱30,000 |

| Annual Gross Rent | ₱360,000 | ₱360,000 |

| Annual RPT + SEF | ₱0 | ₱18,000 |

| Net Income Before Other Costs | ₱360,000 | ₱342,000 |

| Effective Annual Yield | Overstated | Realistic |

This example isolates property tax only. HOA dues, maintenance, vacancies, and income tax will further affect net yield.

Across property types, RPT is rarely the biggest cost—but it is one of the most predictable.

RPT as Part of Annual Operating Expenses

RPT sits alongside association dues, maintenance, insurance, and management fees. Unlike repairs or vacancies, RPT is predictable. It accrues every year regardless of occupancy. Treating it as optional or “to be settled later” distorts cash-flow analysis and creates artificial returns on paper.

Disciplined investors budget RPT annually, settle early to capture discounts, and keep records clean to preserve liquidity.

Impact on Rental Yield and ROI

RPT directly reduces net yield. In urban markets—particularly Metro Manila—the combined basic RPT and Special Education Fund (SEF) often consume 3% to 8% of gross annual rent, depending on assessed value and classification.

Example perspective:

- Gross annual rent: ₱360,000

- Total annual RPT + SEF: ₱18,000

- Immediate reduction: 5% of gross income

That reduction compounds once HOA dues, maintenance, vacancy allowance, and income tax are added. Investors who ignore RPT tend to overstate ROI and misprice rentals.

Forecasting RPT Increases

RPT does not increase randomly. The most common triggers are:

- General revision of assessments by the LGU

- Change in property classification (residential to commercial)

- Recorded improvements or renovations

- Area-wide valuation updates due to infrastructure growth

Long-term investors should assume periodic upward adjustments and stress-test cash flow accordingly. Conservative underwriting survives reassessment cycles; aggressive assumptions do not.

Managing Multiple Properties

For portfolio owners, RPT management becomes an operational discipline:

- Track RPT per property annually

- Centralize receipts and tax declarations

- Calendar deadlines to avoid penalties

- Standardize early payment to capture discounts

Small inefficiencies multiplied across several properties turn into material losses over time.

Long-Term Hold vs Flip Considerations

Long-term holds

RPT becomes a steady carrying cost. The objective is predictability, compliance, and minimal friction during eventual exit.

Flips and short-term holds

RPT still matters. Delinquency—even for a short period—can delay resale and eat into margins. Buyers will not absorb your unpaid taxes.

In both strategies, RPT is not negotiable. It is part of the cost of doing business in real estate.

Common Myths and Costly Property Tax Mistakes

Property tax problems in the Philippines are rarely caused by complexity. They are caused by beliefs that feel reasonable but are legally wrong. These myths persist because consequences show up late—often at the worst possible time. Below are the most common (and expensive) misconceptions.

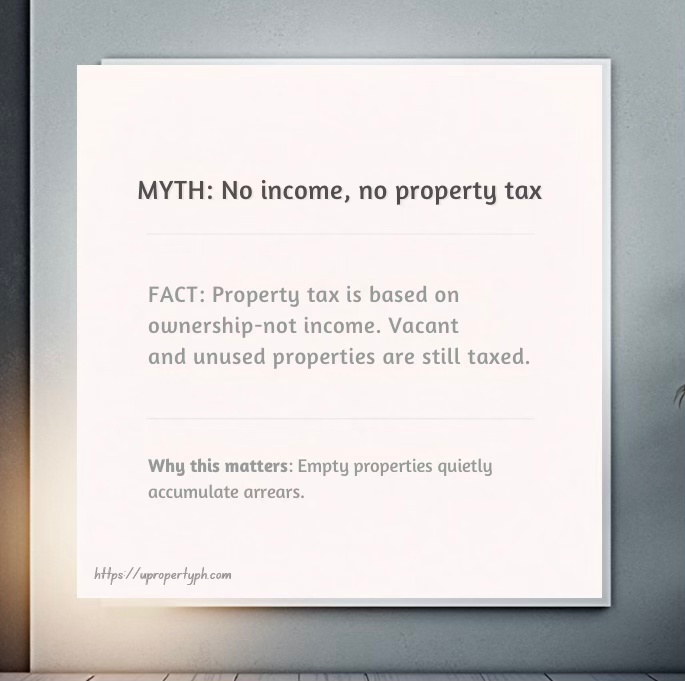

Myth 1: “No income, no tax.”

Fact: Real Property Tax is triggered by ownership, not income.

A vacant lot, an unused condo, or a house sitting empty for years still accrues RPT annually. Many owners discover five to ten years of arrears only when they attempt to sell or transfer the property.

Why it’s costly: Back taxes must be settled in full before any transaction can proceed. There is no “income exemption.”

Myth 2: “Condo dues already cover property tax.”

Fact: Condominium association dues and RPT are entirely separate.

Dues pay for building operations—security, maintenance, amenities—not government taxes.

Why it’s costly: Condo owners often skip RPT payments for years, assuming dues cover everything. The mistake surfaces only during resale, loan application, or title verification.

Myth 3: Ignoring tax declaration updates after renovations

Fact: Significant renovations and improvements affect assessed value and must be reflected in tax declarations.

Failing to update records creates mismatches between the physical property and LGU records.

Why it’s costly:

- Understated improvements can trigger penalties once discovered

- Overstated or outdated improvements inflate taxes unnecessarily

- Mismatches delay title transfers and bank approvals

Accuracy protects both cash flow and transaction timelines.

Myth 4: “Inheritance pauses property tax obligations.”

Fact: Property tax does not stop when the owner dies.

RPT continues to accrue during estate settlement—even if the property is under dispute or unused.

Why it’s costly: Many inherited properties accumulate years of unpaid RPT while heirs delay action. When settlement finally begins, the tax bill becomes a major obstacle, compounding legal and emotional stress.

Myth 5: Overlooking idle land tax exposure

Fact: Vacant or underutilized land may be classified as idle, subjecting it to additional taxation depending on LGU ordinances.

Why it’s costly: Owners who hold land long-term without development often underestimate carrying costs. Idle land tax can materially change the economics of land banking strategies.

Practical Tools and Checklists

Understanding property tax is useful. Operationalizing it is where value is created. This section turns knowledge into action—reducing risk, saving time, and preventing last-minute surprises. These tools are designed to be practical, repeatable, and transaction-ready, which is why they consistently convert readers into qualified inquiries.

Annual RPT Compliance Checklist (For Owners & Landlords)

Use this once a year—preferably in January—to keep records clean and predictable.

- Confirm current tax declaration number and property classification

- Verify assessed value against the latest assessment notice

- Check eligibility for early payment discounts

- Settle basic RPT and SEF in full or schedule quarterly payments

- Secure and archive official receipts (digital + physical copies)

- Calendar the next payment cycle

Outcome: No penalties. No scrambling. No transaction delays.

Buyer RPT Due Diligence Checklist

Buyers should treat RPT verification with the same rigor as title review.

- Request certified copies of recent RPT receipts

- Confirm no delinquency or arrears with the treasurer’s office

- Match tax declaration details (area, improvements) with the title

- Check for idle land classification (if applicable)

- Require settlement of any gaps before closing

Outcome: You avoid inheriting someone else’s tax problem.

Seller Pre-Transfer Checklist (Before Listing)

This checklist shortens selling timelines and strengthens buyer confidence.

- Settle all outstanding RPT and SEF

- Reconcile tax declaration vs actual condition (renovations, additions)

- Resolve classification issues (residential vs commercial)

- Secure certified true copies of receipts

- Coordinate early with the assessor if corrections are needed

Outcome: Faster closing, fewer renegotiations, smoother title transfer.

Questions to Ask the Assessor or Treasurer

Bring clarity to LGU conversations by asking the right questions.

- Is the property classification correct based on current use?

- When was the last general revision of assessments?

- Are there pending adjustments or notices on record?

- Is the property flagged as idle land?

- What payment options and discounts apply this year?

Outcome: Fewer assumptions. Better decisions.

Get the Right Property Tax Checklist—In One Place

Practical, transaction-ready checklists for Philippine property owners, buyers, and sellers. Choose what you need and download instantly.

Why Property Tax Compliance Protects Property Value

Property tax compliance is rarely framed as a value driver—but it should be. In practice, clean and current real property tax (RPT) records function as asset insurance. They protect not just against penalties, but against friction, delay, and lost opportunities.

Compliance as Asset Protection

A property with complete, verifiable RPT records is a defensible asset. There are no hidden liabilities waiting to surface, no back taxes that must be negotiated at the last minute, and no procedural gaps that invite delay.

Non-compliance does the opposite. It introduces uncertainty. And in real estate, uncertainty always reduces value—even if the structure itself is sound.

Liquidity and Resale Readiness

Liquidity is the ability to convert an asset into cash without delay or discount. In the Philippine market, RPT compliance is a prerequisite for liquidity.

Properties that are:

- Fully paid up on RPT and SEF

- Backed by clean, organized receipts

- Aligned between title and tax declaration

Move faster. Buyers proceed with confidence. Banks release funds on schedule. Title transfers clear without friction.

Properties with tax gaps often sell at a discount—or not at all.

Why Disciplined Owners Transact Faster

Experienced buyers, brokers, and lenders can spot tax issues early. When they see incomplete RPT records, they assume delays and risk. When they see clean compliance, they assume professionalism and preparedness.

Disciplined owners benefit in three ways:

- Shorter transaction timelines

- Fewer renegotiations

- Stronger buyer trust

In competitive markets, that difference matters.

LGU Funding and Long-Term Property Value

Property tax does not disappear into abstraction. It funds local infrastructure, schools, public services, and disaster preparedness—all of which directly influence neighborhood desirability and property values.

Well-funded LGUs tend to deliver:

- Better roads and access

- More reliable utilities

- Stronger public services

Over time, these translate into higher demand and more resilient property values. Compliance, at scale, improves the very environment that sustains real estate appreciation.

Conclusion

Property tax in the Philippines is not unpredictable. It only feels that way when it is ignored.

Once you understand how real property tax is assessed, computed, paid, and enforced, it becomes one of the most manageable aspects of property ownership. The system follows clear rules. The deadlines are known. The consequences are consistent. What turns RPT into a problem is not the amount—it is neglect.

Most stalled sales, delayed title transfers, and frozen inheritances are not caused by excessive tax. They are caused by years of inaction that surface at the exact moment movement is required. That is a preventable failure.

The path forward is straightforward:

- For property owners: treat RPT as annual asset maintenance, not a future problem

- For buyers: verify RPT with the same rigor as the title

- For investors and landlords: price RPT into returns and plan for reassessments early

Control beats compliance. Preparedness beats urgency.

Take the Next Step (Before You Need To)

If you are planning to buy, sell, inherit, or invest in property, act while you still have leverage and time.

- Request a property due diligence review to identify tax, title, and compliance issues early

- Download a pre-sale compliance checklist to shorten timelines and avoid last-minute surprises

- Speak with a broker before buying or selling to ensure the property is transaction-ready

Property tax does not reward attention. It punishes neglect. Handle it early, and the rest of the transaction moves with speed and confidence.

Leave a comment