A close-up view of a Transfer Certificate of Title being signed during a property transaction meeting.

Across the Philippines, there are properties that are fully paid, occupied, and even renovated—yet remain unsellable. The problem is rarely sensational. No scam. No lawsuit. Just a Deed of Sale treated as routine paperwork. Years later, that oversight shows up when titles can’t be transferred, resales fall through, or banks refuse financing. The property stands there, paid for and occupied, but legally frozen.

This usually traces back to one persistent misconception: signing a Deed of Sale does notcomplete ownership. It formalizes intent and agreement, yes. But ownership transfer in the Philippines is a chain process involving taxes, registration, and compliance. When the Deed of Sale is flawed—or treated as a mere formality—that entire chain weakens.

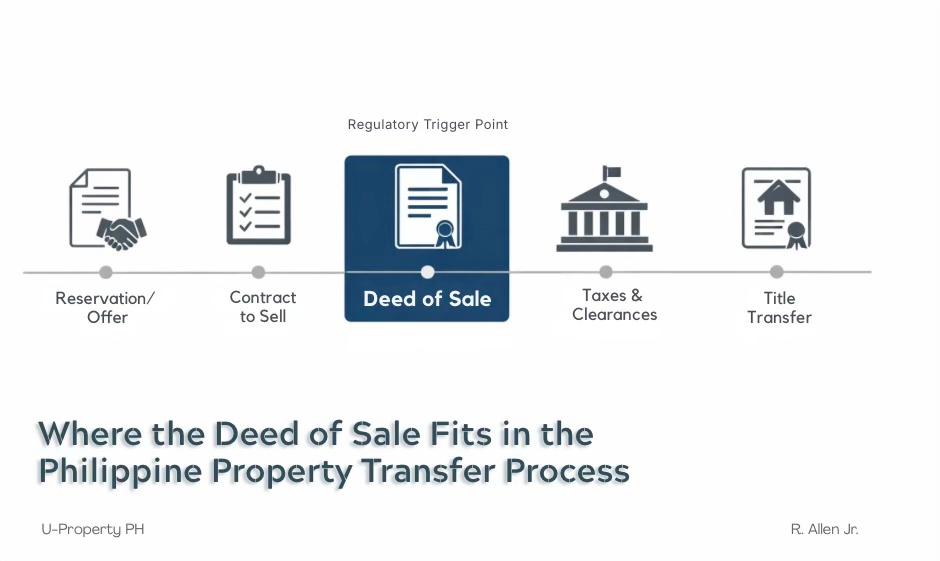

The Deed of Sale marks the transition from private agreement to government-regulated property transfer in the Philippines.

This guide is designed to correct that thinking. You’ll learn what a Deed of Sale actually does under Philippine law, where it fits in the transaction timeline, and why its wording, structure, and execution directly affect taxes, title transfer speed, and future resale value. More importantly, you’ll see how a properly prepared Deed of Sale protects your money upfront, prevents delays, and preserves your ability to sell or leverage the property years down the line.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What a Deed of Sale Really Is Under Philippine Law (And What It Does Not Do)

- Types of Deeds of Sale Commonly Used in Philippine Property Transactions

- Where the Deed of Sale Fits in the Philippine Property Transfer Process (BIR, LGU, Registry of Deeds)

- Essential Components of a Philippine Deed of Sale (What Must Be Correct)

- Taxes and Costs Triggered by the Deed of Sale in the Philippines

- Common Deed of Sale Mistakes That Delay or Kill Property Deals

- Buyer’s Guide: What to Verify Before Signing a Deed of Sale

- Seller’s Guide: How to Protect Yourself Through the Deed of Sale

- Investor and Secondary Market Considerations for Deeds of Sale

- Why Legal Review Is Not Optional for Deeds of Sale (Even “Simple” Sales)

- Real Philippine Case Scenarios Involving Deeds of Sale

- Practical Deed of Sale Checklists and Best Practices

- The Deed of Sale as a Risk Management Tool, Not Paperwork

- Verify Before You Sign a Deed of Sale

What a Deed of Sale Really Is Under Philippine Law (And What It Does Not Do)

👉 A Deed of Sale may be legally valid between the parties yet still be unregistrable if it fails to meet tax, form, or authority requirements.

This is where legal theory and real-world consequences begin to diverge.

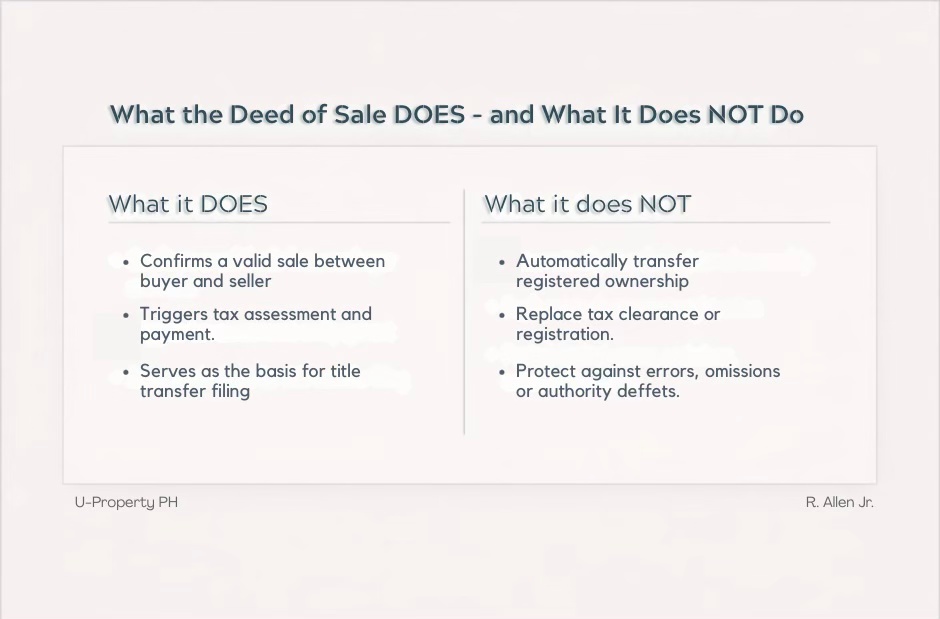

Under Philippine law, a Deed of Sale is the written contract that evidences an agreement between a seller and a buyer to transfer ownership of a specific property for a price. Its legal foundation rests on the Civil Code provisions on contracts and sales, which require three elements to exist simultaneously: consent of the parties, a determinate subject matter, and a certain price. When these elements are properly documented and the deed is duly notarized, the sale is binding and enforceable between the parties.

However, a Deed of Sale may be legally valid and still be unregistrable if it fails to comply with tax, form, or authority requirements.

This is where many transactions go off-track. In practice, the Deed of Sale is often treated as a mere “requirement”—something to be signed after payment, filed away, and forgotten. That view is incomplete and risky. The Deed of Sale does more than record payment. It triggers tax obligations, supports registration with the Registry of Deeds, and serves as the primary legal basis for transferring title. If it is vague, inconsistent, or improperly executed, every step that follows becomes vulnerable to delay or outright rejection.

The distinction that matters most is between legal weight and practical consequence. Legally, a notarized Deed of Sale is a public document with evidentiary value and presumption of regularity.

The Deed of Sale marks the transition from private agreement to government-regulated property transfer in the Philippines.

Practically, it does not, by itself, make the buyer the registered owner. Ownership becomes opposable to third parties only after taxes are settled and the transfer is recorded with the Registry of Deeds. This is one of the most commonly misunderstood points in Philippine property transactions.

Understanding this distinction changes how the document should be treated. A properly drafted Deed of Sale is not paperwork used to finish a deal; it is the legal spine of the entire transaction. Everything downstream—tax clearance, title issuance, and future resale readiness—depends on how sound it is.

Types of Deeds of Sale Commonly Used in Philippine Property Transactions

👉 Using the wrong type rarely voids a sale—but it almost always delays it.

Not all Deeds of Sale serve the same function. The form used must reflect how the transaction is actually structured: when payment occurs, whether a loan is involved, and how risk is allocated. When the deed does not match the deal, friction surfaces later—usually at the bank, the BIR, or the Registry of Deeds.

Absolute Deed of Sale (Cash and Bank-Financed Transactions)

This is the most common form used in Philippine resale transactions and is intended to transfer ownership immediately. In cash purchases, it is typically executed only after full payment has been made.

In bank-financed transactions, however, it is standard for the Absolute Deed of Sale to be signed and notarized before the seller receives the loan proceeds—provided the buyer’s loan has already been approved and the bank has issued a Letter of Guarantee in favor of the seller. This sequencing is a frequent source of confusion among buyers, sellers, and even brokers.

The real risk is not signing before loan release. It is signing without a Letter of Guarantee or without clearly stating in the deed that payment will be satisfied through loan proceeds upon completion of title transfer and mortgage annotation. When these safeguards are missing, the transaction becomes vulnerable to breakdowns during tax assessment, registration, and enforcement.

Conditional Deed of Sale (Pending Loan or Installment Sales)

A Conditional Deed of Sale is used when the transaction depends on conditions that must first be fulfilled. Common examples include pending loan approval, issuance of a Letter of Guarantee, installment payment arrangements, or unresolved documentation. Ownership transfer is deferred until these conditions are met.

Problems arise when the deed is treated as a placeholder. Conditions that are vague, open-ended, or poorly defined invite disputes and stall the transaction. A conditional deed does not reduce risk unless its conditions are objective, time-bound, and enforceable.

Deed of Sale with Assumption of Mortgage (Secondary Market Sales)

This structure applies when the buyer assumes the seller’s existing loan, subject to lender approval. It is common in secondary market condominium sales where the original mortgage remains outstanding.

Here, alignment with the bank is critical. Without the lender’s formal consent, the assumption is invalid—regardless of what the Deed of Sale states. This makes mortgage assumption one of the most error-prone deed structures in practice.

When Each Is Used in Real Transactions

The correct deed follows the actual flow of money and obligations—not convenience. Cash transactions favor absolute deeds executed after payment. Loan-backed purchases often begin with conditional deeds and conclude with an absolute deed once the Letter of Guarantee is released. Mortgage assumptions require bank coordination before any deed is signed.

Using the wrong type may not invalidate the sale outright, but it almost always delays taxes, title transfer, or future resale.

Comparison overview:

1. Absolute Deed of Sale

When used

Fully paid transactions, completed bank-financed purchases

Key risk

Signed before full payment or LoG release

Best for

Cash buyers, clean secondary market resales

2. Conditional Deed of Sale

When used

Pending loan approval or installment arrangements

Key risk

Poorly defined conditions and timelines

Best for

Buyers relying on financing or staged payments

3. Deed of Sale with Assumption of Mortgage

When used

Buyer takes over seller’s existing loan

Key risk

No formal lender approval

Best for

Secondary market buyers seeking lower upfront cash outlay

Where the Deed of Sale Fits in the Philippine Property Transfer Process (BIR, LGU, Registry of Deeds)

👉 This is the point where private agreements become government-controlled.

In a Philippine property transaction, the Deed of Sale marks the transition from private agreement to state-recognized transfer. Everything before it is contractual. Everything after it is regulatory. Confusing these phases is one of the most common reasons transfers stall.

On paper, the sequence looks simple. A reservation or offer signals intent. A contract to sell or similar agreement sets conditions and timelines. The Deed of Sale then formalizes the sale. Only after this document is properly executed can taxes be assessed and paid, and only after taxes are cleared can the title be transferred. The steps appear linear, but in practice they are tightly interdependent.

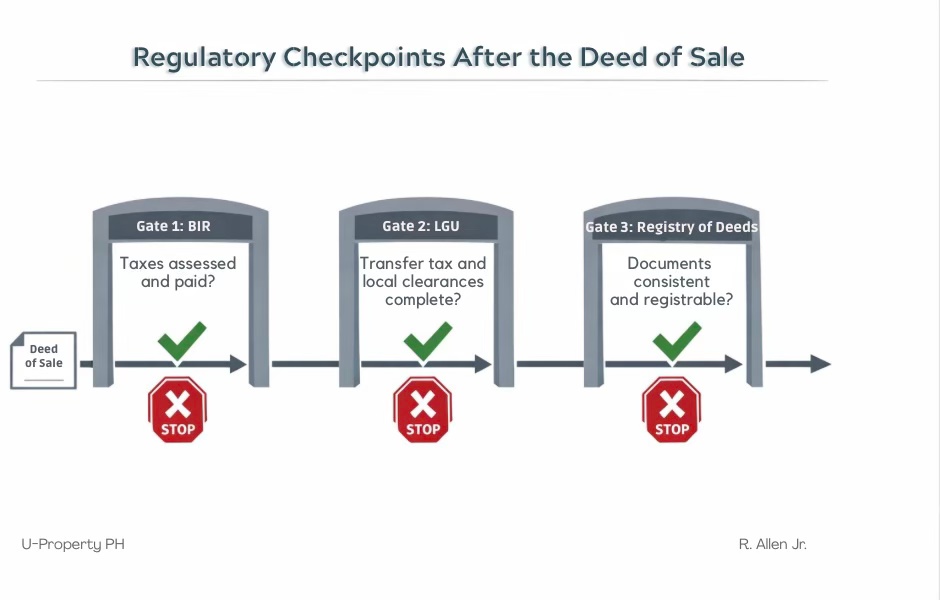

Once the Deed of Sale is notarized, the transaction moves into the compliance phase. The Bureau of Internal Revenue uses the deed as the basis for computing Capital Gains Tax or Creditable Withholding Tax, as well as Documentary Stamp Tax. Local government units rely on it to assess and collect transfer taxes and update tax declarations.

After the Deed of Sale, property transfers must pass independent regulatory checkpoints at the BIR, LGU, and Registry of Deeds.

The Registry of Deeds, in turn, will not process a title transfer unless the Deed of Sale is consistent with all supporting tax clearances and supporting documents. A single discrepancy—wrong price declaration, incorrect property description, mismatched names—can cause the entire process to stop. This is one of the most common rejection points at the Registry of Deeds.

Errors at the Deed of Sale stage are disproportionately costly because they cascade. A flaw in the deed leads to BIR findings, delayed LGU payments, and rejected registry filings. In bank-financed transactions, loan release is further delayed because mortgage annotation cannot proceed. What should be a predictable transfer timeline quickly becomes open-ended.

The Deed of Sale is the pivot point of the entire process. When it is accurate, aligned with the transaction structure, and compliant with regulatory requirements, the transfer moves forward smoothly. When it is not, every office downstream turns from a checkpoint into a gatekeeper.

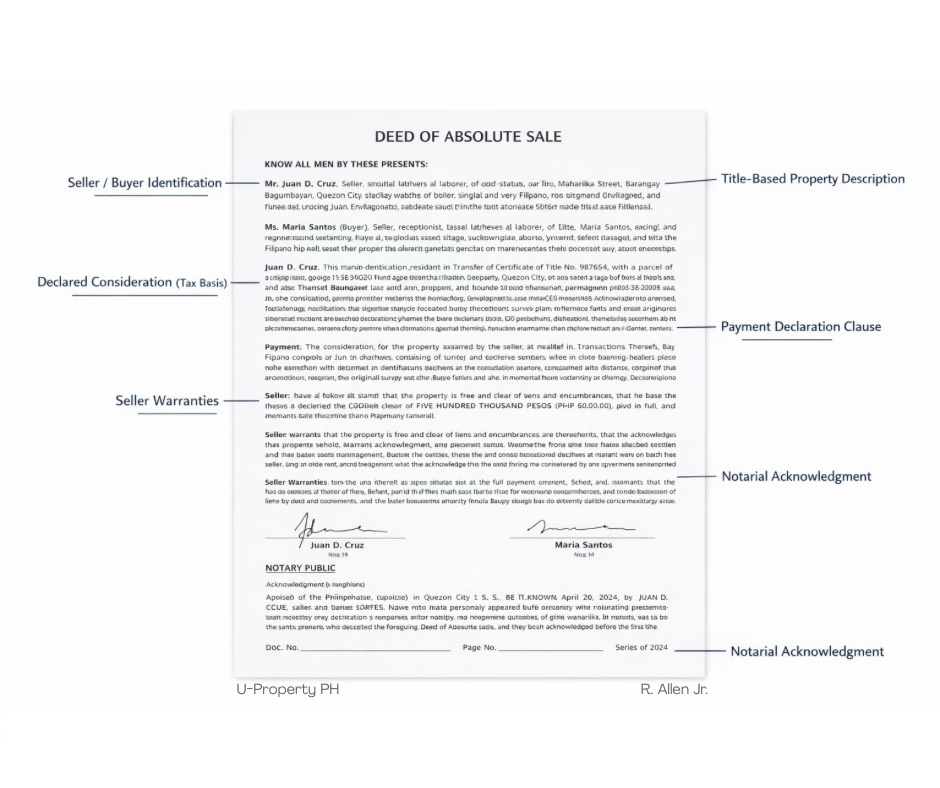

Essential Components of a Philippine Deed of Sale (What Must Be Correct)

👉 This is where most transfers quietly fail.

A Deed of Sale only works if every component reflects reality—who is selling, what is being sold, how payment is made, and when responsibility shifts. Most failed transfers don’t collapse because of a single major flaw, but because several small inaccuracies compound and surface during tax assessment or registration.

Key clauses in a Deed of Sale that directly affect tax assessment, registration, and enforceability.

Parties to the Sale

The deed must accurately identify who has legal authority to sell and who is acquiring ownership. For individual sellers, names must match the title and government-issued IDs exactly. Even minor inconsistencies—extra initials or missing middle names—are enough to trigger questions at the Registry of Deeds.

For corporate sellers, authority must be supported by board resolutions, secretary’s certificates, and proof that the signatory is authorized to sell. Estate and inherited property sales are more complex. Heirs must either execute the sale jointly or provide a legally valid authority to represent the estate. Anything less leaves ownership unresolved.

Property Description and Technical Accuracy

The property description must mirror the title, not marketing materials. This includes the Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) or Condominium Certificate of Title (CCT) number, lot or unit number, floor area, and technical boundaries where applicable. Floor plans, brochures, and tax declarations are not substitutes for title data.

Common errors—outdated title numbers, incorrect unit designations, or mismatches between title and tax declaration details—are routinely flagged by the BIR and the Registry of Deeds. Corrections at this stage usually mean amendments, re-filing, and additional cost.

Selling Price, Declared Consideration, and Payment Structure

The deed must clearly state the selling price and how payment will be made. Payment structure should be unambiguous:

- lump-sum payments, settled in full before execution; or

- installment arrangements, with defined schedules, conditions, and consequences for delay.

This section also carries tax consequences. Under-declared consideration may reduce upfront taxes, but it increases audit risk and complicates future resale when recorded values no longer reconcile.

Warranties, Representations, and Seller Obligations

These clauses allocate risk. Sellers typically warrant that they are lawful owners, that the title is clean, and that the property is free from liens, encumbrances, or adverse claims unless disclosed. Buyers often overlook this section, yet it becomes critical when issues surface after signing.

Outstanding association dues, unpaid real property taxes, or unregistered easements commonly emerge later. Without clear representations and obligations, resolving these issues turns into negotiation rather than enforcement.

Possession, Turnover, and Risk Allocation

Ownership transfer and physical possession do not always occur at the same time. The Deed of Sale should specify when possession is delivered, who bears the risk of loss or damage, and how utilities and association responsibilities are handled during any transition period. Ambiguity here leads to disputes over repairs, insurance claims, and liability between signing and turnover.

Signatures, Witnesses, and Notarization

A Deed of Sale that is not properly notarized remains a private document with limited evidentiary value. Notarization converts it into a public instrument—acceptable to banks, the BIR, and the Registry of Deeds. Witnesses must be present, competent, and properly identified. Skipping or mishandling this step renders even a well-drafted deed practically unusable.

Taken together, these components determine whether the Deed of Sale accelerates the transfer or becomes the reason it stalls. Precision here is not legal overkill—it is transaction insurance.

Taxes and Costs Triggered by the Deed of Sale in the Philippines

👉 Once the Deed of Sale is signed, taxes stop being optional and start being time-bound.

The moment a Deed of Sale is signed and notarized, it stops being a private agreement and becomes a tax-triggering document. In the Philippines, this single document determines not only how much tax is due, but also which office collects it, when it must be paid, and whether the title transfer can move forward at all. Misunderstanding this stage is one of the most expensive mistakes in a property transaction.

| Cost Item | Typical Rate / Range | Who Usually Pays | When Triggered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Gains Tax (CGT) | ~6% of higher of selling price or zonal value | Seller | Upon execution of Deed of Sale |

| Creditable Withholding Tax (CWT) | ~1%–6% depending on classification | Buyer (withheld for seller) | Upon execution of Deed of Sale |

| Documentary Stamp Tax (DST) | ~1.5% of higher of selling price or zonal value | Buyer | Upon execution of Deed of Sale |

| Transfer Tax (LGU) | ~0.5%–0.75% | Buyer | After BIR clearance |

| Registration Fees | Variable (sliding scale) | Buyer | Upon title transfer |

| Notarial Fees | Variable (often % or fixed) | Negotiable | Upon notarization |

Typical taxes and fees triggered by a Deed of Sale in Philippine property transactions.

Capital Gains Tax vs. Creditable Withholding Tax

For individual sellers of real property classified as capital assets, the sale is generally subject to Capital Gains Tax (CGT). The tax is computed at a fixed rate based on the higher of the selling price, the zonal value, or the fair market value stated in the tax declaration. The BIR relies heavily on the figures stated in the Deed of Sale when making this assessment.

For corporate sellers or properties considered ordinary assets, the transaction is instead subject to Creditable Withholding Tax (CWT). This shifts part of the tax compliance burden to the buyer, who withholds and remits the tax on behalf of the seller. Using the wrong tax classification—or drafting a deed that contradicts the seller’s actual status—almost guarantees delays during BIR processing.

Documentary Stamp Tax

Documentary Stamp Tax (DST) is imposed on the privilege of transferring ownership. Like CGT or CWT, it is computed based on the consideration stated in the Deed of Sale or the applicable zonal value, whichever is higher. Even when parties privately agree on alternative valuations, the BIR will default to the deed. Any inconsistency between the deed and supporting documents invites reassessment.

Transfer Tax and Registration Fees

After BIR clearance, local government units impose a transfer tax, usually computed as a percentage of the selling price or fair market value. Only after this is paid can the Registry of Deeds assess registration fees and process the issuance of a new Transfer Certificate of Title or Condominium Certificate of Title. At this stage, the Deed of Sale is again reviewed for consistency. Errors that slipped through earlier often resurface here, forcing corrections that restart the process.

Under-Declaration Risks and Audit Exposure

Under-declaring the selling price in the Deed of Sale is often rationalized as a tax-saving measure. In reality, it is a short-term gain with long-term consequences:

- higher audit and reassessment risk from the BIR and;

- distorted acquisition cost, which complicates future resale and tax computation.

Many reassessments begin not at resale, but during routine BIR processing of title transfers. What looks like savings upfront often turns into friction later. In practical terms, the Deed of Sale sets the tax narrative of the transaction. Once filed, that narrative is difficult—and expensive—to change.

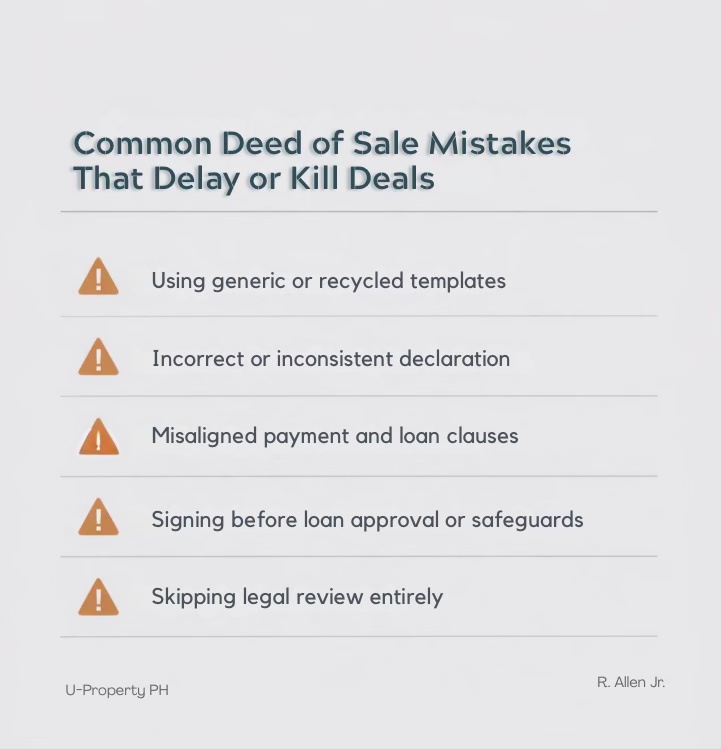

Common Deed of Sale Mistakes That Delay or Kill Property Deals

👉 None of these mistakes look serious—until they’re irreversible.

Most failed property transfers in the Philippines don’t collapse because of fraud or bad intent. They fail because the Deed of Sale was treated as routine paperwork. The mistakes are predictable, common, and costly.

Most of these issues surface only after documents are submitted—not at signing.

Using Generic Templates

Downloadable templates and recycled deeds from past transactions are a common starting point—and a common failure point. Templates rarely reflect the actual structure of the deal, the seller’s legal status, or the buyer’s financing arrangement. What works for a cash condo resale does not work for an estate sale or a bank-financed purchase. When the deed doesn’t match reality, government offices flag it at filing.

Incorrect or Inconsistent Price Declaration

Declaring a price that does not align with payment receipts, loan documents, or zonal values creates friction at the BIR. Even when under-declaration slips through initial filing, it resurfaces later during resale, audit, or financing. Inconsistent figures across documents almost always lead to reassessment or rejection.

Misaligned Payment Clause

Misaligned payment clauses create legal ambiguity, especially when they fail to reflect how payment actually occurs:

- Bank loans not referenced.

- Letters of Guarantee omitted.

- Installment schedules left vague.

In disputes, the deed—not side agreements—controls.

Signing Before Loan Approval

In bank-financed transactions, signing an Absolute Deed of Sale before loan approval and issuance of a Letter of Guarantee exposes the seller to unnecessary risk. Without bank commitment, the seller has transferred ownership on paper without certainty of payment. This mistake commonly results in stalled transfers or forced amendments.

Skipping Legal Review

Perhaps the most underestimated risk. Many parties assume that notarization equals legal review. It does not. Notaries verify identities and signatures; they do not validate deal structure or protect either party’s interests. Without legal review, structural defects in the Deed of Sale often surface only during filing, tax assessment, or enforcement

The pattern is consistent: shortcuts taken at the Deed of Sale stage rarely save time or money. They simply postpone the cost until it becomes embedded in the transaction. Most of these issues surface only after documents are submitted—not at signing.

Avoiding these mistakes is about execution; preventing them entirely requires structure.

Buyer’s Guide: What to Verify Before Signing a Deed of Sale

👉 After notarization, buyers lose leverage—and gain liability.

For buyers, the Deed of Sale is the point of no return. Once it is signed and notarized, leverage shifts, timelines begin to run, and taxes are triggered. Due diligence done after signing is damage control. Due diligence done before signing is protection.

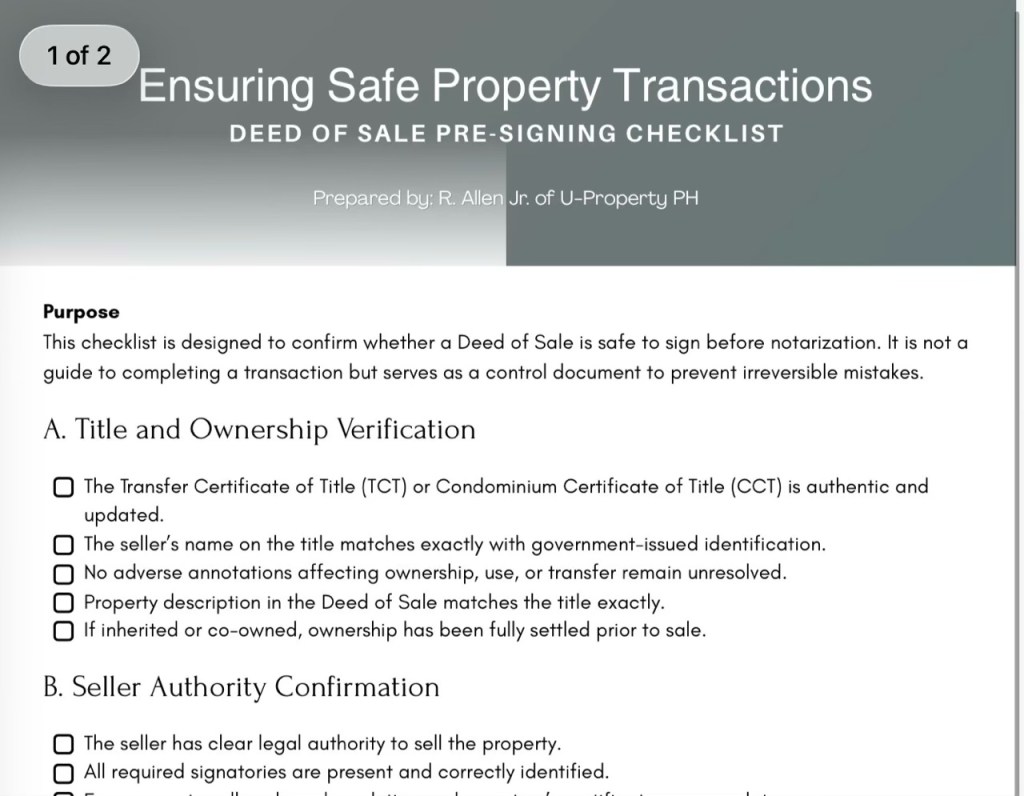

Title and Ownership Checks

Start with the title, not the unit or the house. Verify that the Transfer Certificate of Title or Condominium Certificate of Title is authentic, current, and free from adverse annotations that affect ownership or use. The seller’s name on the title must match exactly with the name in the Deed of Sale and their identification documents. Even minor discrepancies can delay registration later.

If the property was inherited, confirm that ownership has been properly settled. A Deed of Sale signed by only one heir does not transfer ownership if other heirs retain legal rights. Buyers usually discover this problem only when the Registry of Deeds refuses to process the transfer.

Seller Authority

Before signing, the buyer’s role is not to validate authority line by line, but to confirm that authority is complete, documented, and final. If the seller’s authority depends on missing resolutions, unsigned heir consents, pending court appointments, or post-signing promises, the buyer should pause.

Authority issues do not resolve themselves after notarization. Once the Deed of Sale is signed, the Registry of Deeds will assess authority strictly—and rejection at that stage leaves the buyer without leverage.

If authority is not fully settled before signing, the correct move is not negotiation. It is refusal to sign.

Loan and Payment Alignment

In bank-financed transactions, the Registry of Deeds will only process title transfers based on an Absolute Deed of Sale declaring that the seller has been paid in full. It does not require disclosure of loan structures, payment breakdowns, or Letters of Guarantee. This disconnect between registry requirements and bank processes is a recurring source of buyer–seller tension.

For buyers, the implication is simple: loan approval and issuance of a Letter of Guarantee must already be in place before signing. Once the Absolute Deed of Sale is notarized, the Registry treats the sale as final, regardless of how payment is structured behind the scenes.

Protective Clauses Buyers Should Insist On

A buyer-protective Deed of Sale does more than confirm the transaction. It manages risk before ownership transfers. Buyers should insist on warranties that the title is clean, that all real property taxes and association dues are certified as fully paid and current as a condition to signing, and that the property is free from undisclosed liens or occupants.

Clauses clearly defining possession terms, representations, and remedies for misrepresentation should operate as conditions precedent to signing, not afterthoughts.

The discipline is simple: if a risk matters enough to worry about, it matters enough to be written into the Deed of Sale—before you sign.

Seller’s Guide: How to Protect Yourself Through the Deed of Sale

👉 For sellers, the biggest risk is not unpaid price—it’s unfinished exposure.

For sellers, the Deed of Sale is both a transfer document and a risk boundary. Once it is signed and notarized, ownership is acknowledged as transferred, taxes are triggered, and leverage shifts. A well-drafted deed protects payment, limits future liability, and prevents disputes long after the property has changed hands.

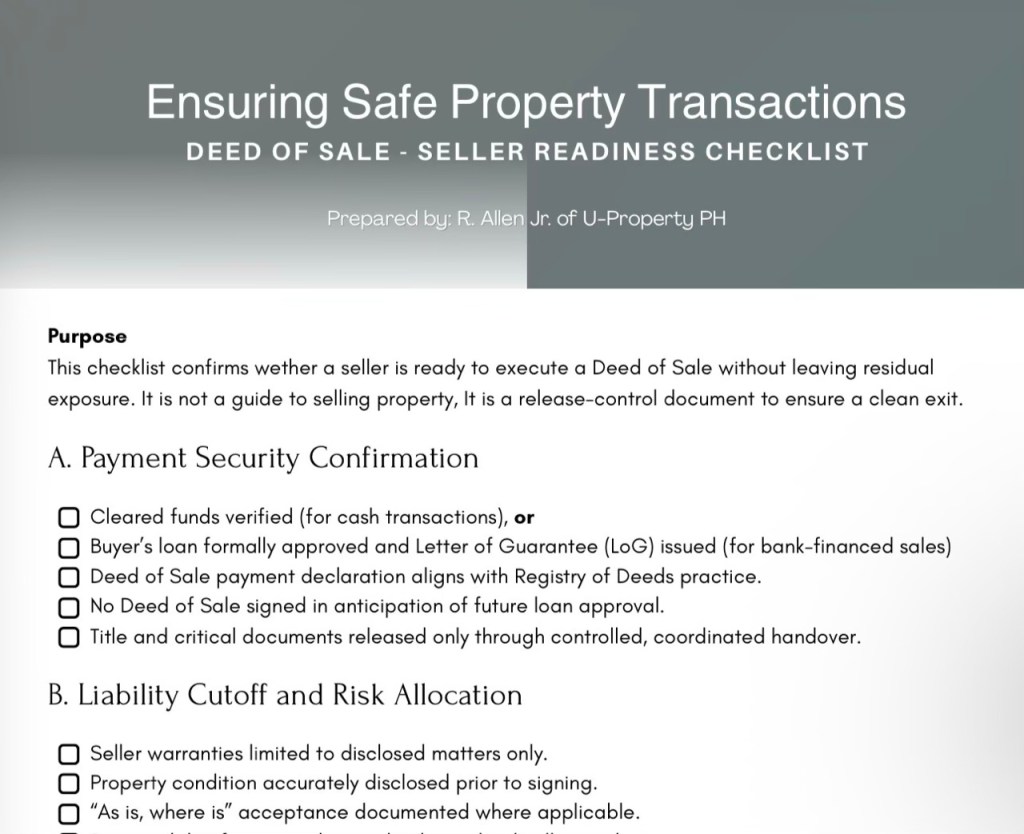

Payment Security Strategies

For sellers, the real risk is not non-payment—it is mis-timed payment. In cash transactions, protection is straightforward: the Deed of Sale should be executed only after funds are cleared and verifiable. In bank-financed deals, protection comes from structure. Sellers should sign only after the buyer’s loan has been approved and the bank has issued a Letter of Guarantee.

For registration purposes, the Deed of Sale must declare that the seller has been paid in full. Actual payment security, however, is achieved through internal safeguards—controlled release of the title, coordinated timelines with the bank, and clear sequencing of obligations—so payment is completed once transfer and mortgage requirements are satisfied.

Limiting Post-Sale Exposure

A Deed of Sale should clearly define the seller’s responsibilities and, just as importantly, where those responsibilities end. Sellers should limit warranties to matters within their knowledge and control and avoid open-ended obligations that survive indefinitely. Clauses stating that the buyer accepts the property “as is, where is,” subject to disclosed conditions, help prevent post-sale claims related to defects, alterations, or usage issues that arise after turnover.

Turnover and Utility Handover Clauses

Possession is often assumed but rarely specified. Sellers should ensure the deed clearly states the turnover date, the condition of the property at turnover, and the handling of utilities, association dues, and real property taxes. Without this clarity, sellers may remain on the hook for charges or liabilities incurred after the sale, simply because no formal cutoff was established.

Tax Planning Considerations

While tax rates are fixed, tax outcomes are not. Sellers should determine early whether the transaction is subject to Capital Gains Tax or Creditable Withholding Tax and ensure that the Deed of Sale reflects the correct classification. Misclassification at this stage almost always leads to reassessment during BIR processing.

Under-declaring consideration may appear advantageous in the short term, but it materially increases audit risk and complicates compliance. A properly structured Deed of Sale supports timely tax payment, smooth clearance, and clean closure of the seller’s tax and reporting obligations.

For sellers, protection is not about adding complexity. It is about precision. A Deed of Sale that is aligned with payment flow, turnover reality, and tax obligations allows the seller to exit the transaction cleanly—without lingering risk.

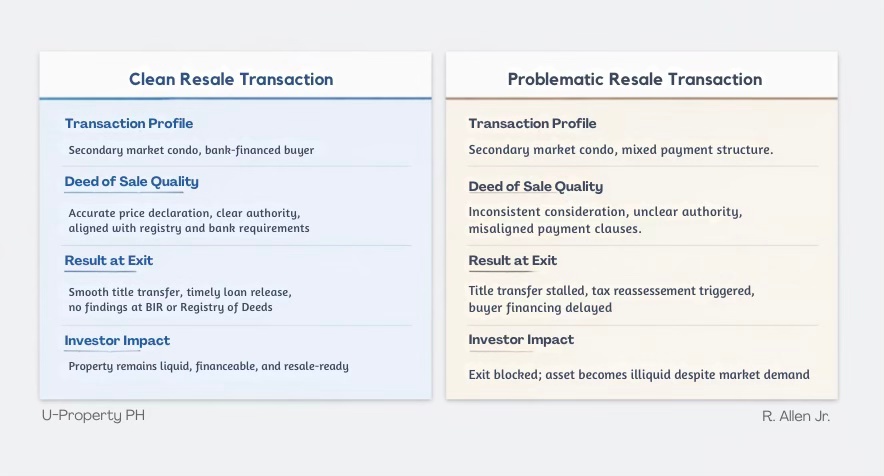

Investor and Secondary Market Considerations for Deeds of Sale

👉 Investors don’t lose money at entry—they lose it at exit.

For investors and secondary market buyers, the Deed of Sale is not just about completing today’s transaction. It determines how liquid, financeable, and defensible the property will be years later. Small drafting shortcuts that seem harmless at acquisition often surface as major obstacles at exit.

The difference between a liquid asset and a trapped one is often decided at acquisition.

Resale vs. Developer Transactions

Developer sales follow standardized documentation and controlled timelines. Secondary market transactions do not. In resales, the Deed of Sale must reconcile years of ownership history, tax compliance, and actual usage. Investors often assume that because a unit is occupied or generating income, the paperwork is clean. That assumption is expensive. A resale Deed of Sale must be airtight because it becomes the reference document for every future transaction involving the property.

Estate Sales and Inherited Properties

Estate and inherited properties carry layered risk. Ownership may be fragmented among heirs, some of whom may be abroad or uncooperative. A Deed of Sale executed without proper settlement of the estate or without authority from all heirs does not create marketable title, regardless of how long the buyer has possessed the property. In discounted estate sales, missing or incomplete authority turns an apparent bargain into a non-liquid asset, regardless of possession or payment

Without complete authority from all heirs or proper estate settlement, the buyer does not acquire marketable title—regardless of possession or payment.

Impact on Future Resale, Leasing, and Refinancing

Banks, buyers, and institutional tenants all review the same documents. A poorly drafted or inconsistent Deed of Sale raises red flags during refinancing, resale due diligence, or even long-term leasing. This is one of the most common reasons secondary market properties fail institutional due diligence.

Under-declared values complicate capital gains computation on exit. Ambiguous warranties make buyers nervous. Missing turnover clarity leads to disputes over possession history. What investors often call a “paper issue” is, in reality, a valuation issue.

For secondary market investors, the discipline is simple: buy as if future buyers, banks, and tenants will scrutinize every document—because they will.

Why Legal Review Is Not Optional for Deeds of Sale (Even “Simple” Sales)

👉 Most real estate problems begin with documents that looked harmless.

Many Philippine property transactions are labeled ‘simple’ because the buyer and seller agree, the price is settled, and no dispute is visible. That label is misleading. Most legal problems in real estate do not arise from disagreement—they arise from documents that fail under scrutiny. Legal review exists to prevent these issues from appearing at all—not to fix them after the fact.

Most real estate problems begin with documents that looked harmless.

Many Philippine property transactions are labeled “simple” because the buyer and seller agree, the price is settled, and no dispute is visible. That label is misleading. Most legal failures in real estate do not arise from disagreement—they arise from documents that cannot withstand scrutiny. Legal review exists to prevent these issues from appearing at all, not to fix them after the fact.

Role of Lawyers, Brokers, and Notaries

Each professional involved in a transaction serves a distinct function. Brokers facilitate the deal, align expectations, and manage timelines. Notaries verify identities, witness signatures, and convert private documents into public instruments. Neither role includes evaluating whether the Deed of Sale properly allocates risk or complies with regulatory requirements.

| Function | Broker | Notary | Legal Review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aligns deal terms | ✓ | — | ✓ |

| Verifies seller authority | — | — | ✓ |

| Confirms title risk exposure | — | — | ✓ |

| Drafts or reviews Deed of Sale clauses | — | — | ✓ |

| Ensures tax and registry alignment | — | — | ✓ |

| Witnesses signatures | — | ✓ | — |

| Converts document to public instrument | — | ✓ | — |

| Facilitates transaction process | ✓ | — | ✓ |

Responsibility matrix showing which transaction risks are addressed by brokers, notaries, and legal review.

Legal review is the only stage where authority, risk allocation, and regulatory alignment are examined together.

Cost of Shortcuts vs. Structural Exposure

Skipping legal review often saves a few thousand pesos upfront while embedding document defects that surface during filing, assessment, or enforcement. A single ambiguous clause can compromise BIR clearance, disrupt title transfer, or obstruct loan release. Correcting a defective Deed of Sale usually requires amendments, re-notarization, and re-filing—each step increasing cost and entrenching procedural risk.

Skipping legal review may save a modest amount upfront, but it embeds document defects that surface during filing, assessment, or enforcement. A single ambiguous clause can compromise BIR clearance, disrupt title transfer, or obstruct loan release. Correcting a defective Deed of Sale typically requires amendments, re-notarization, and re-filing—each step increasing cost and locking in procedural risk.

When Professional Review Is Critical

Legal review is non-negotiable in bank-financed purchases, estate sales, corporate transactions, mortgage assumptions, and any sale involving multiple owners or prior encumbrances. These are not edge cases in the Philippine market; they are common scenarios. Even in clean cash resales, review ensures that the document aligns with registration and tax requirements—not merely with the parties’ understanding.

The discipline is simple. If the property value is significant enough to protect, it is significant enough to review properly. Legal review is not an added layer. It is the layer that prevents everything else from failing.

Real Philippine Case Scenarios Involving Deeds of Sale

👉 Each of these cases failed—or succeeded—at the Deed of Sale stage.

These scenarios are not theoretical. They mirror what actually happens in Philippine property transactions when the Deed of Sale is handled well—or poorly. The difference between a smooth transfer and a stalled deal is almost always in the details.

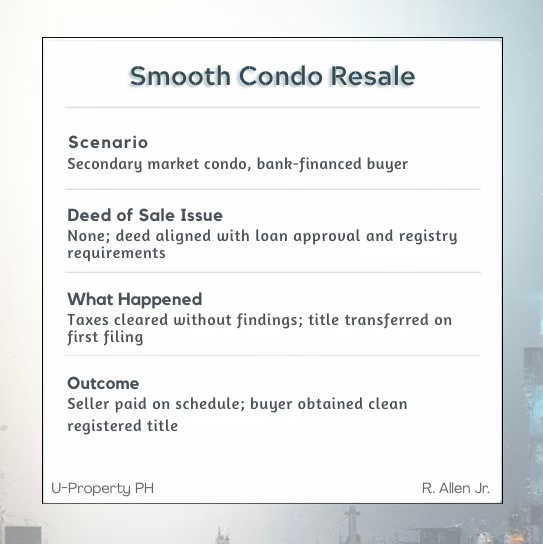

Smooth Condo Resale

Overview of a smooth condo resale process, highlighting key aspects such as scenario, deed of sale issue, what happened, and outcome.

A resale condo in Metro Manila was sold to a bank-financed buyer. The loan was approved early, a Letter of Guarantee was issued, and the Absolute Deed of Sale correctly declared full payment. Names matched the title, taxes were aligned with zonal values, and turnover obligations were clearly defined. BIR clearance was issued without findings, the Registry of Deeds processed the transfer on first filing, and the seller was paid upon mortgage annotation. Total transfer time: under two months. Nothing special happened—and that was the point.

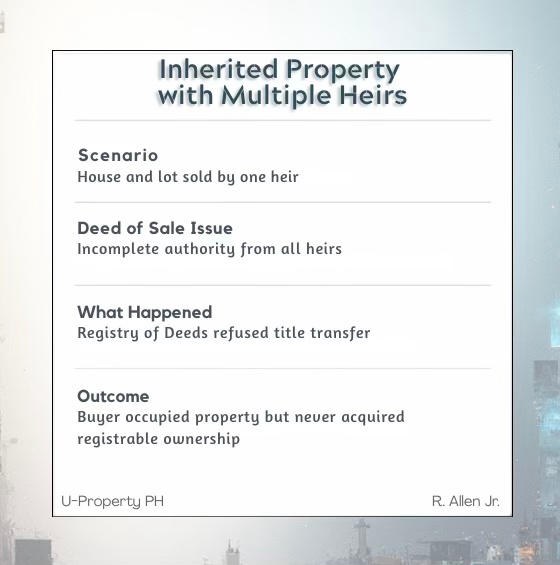

Inherited Property with Multiple Heirs

Understanding the complexities of inherited property transactions involving multiple heirs.

A buyer acquired a discounted house and lot from one heir who claimed authority to sell. The Deed of Sale was executed and notarized, but other heirs had not formally waived their rights. The Registry of Deeds refused to transfer the title. The buyer occupied the property for years without legal ownership, unable to sell or mortgage it. The Deed of Sale was valid on paper, but ineffective in practice because authority was never complete.

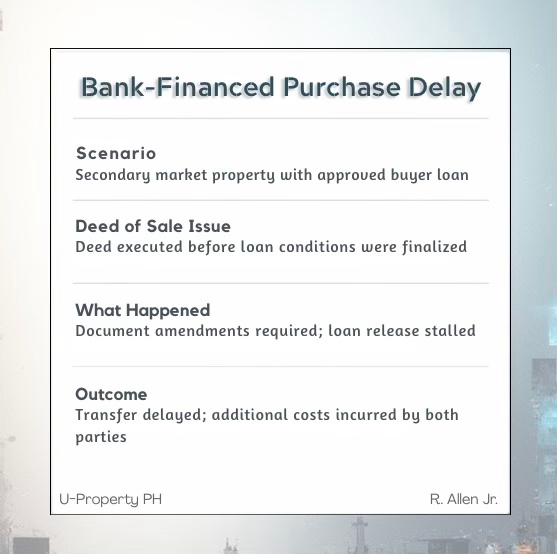

Bank-Financed Purchase Delay

Overview of a bank-financed purchase delay, detailing scenario, issues, and outcomes.

In a secondary market purchase, the buyer and seller signed an Absolute Deed of Sale before loan approval and issuance of a Letter of Guarantee, hoping to “save time.”. The loan was later approved with conditions that required document revisions. Because the deed was already notarized, amendments had to be executed, re-filed, and re-notarized. The title transfer stalled, loan release was delayed, and both parties incurred additional costs. The issue was not the bank—it was premature execution.

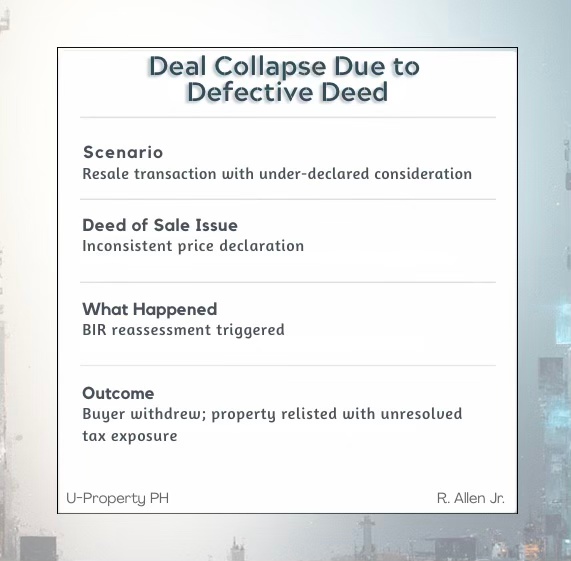

Deal Collapse Due to a Defective Deed of Sale

Analyzing a real estate deal collapse caused by a defective deed, highlighting issues like under-declared consideration and tax exposure.

A property sale collapsed entirely when the BIR flagged inconsistencies between the declared selling price in the Deed of Sale and the payment records. Reassessment followed, penalties were imposed, and the buyer backed out due to mounting delays. The seller had to relist the property, now burdened by unresolved tax issues. The deal failed not because of price or intent, but because the Deed of Sale could not withstand review.

Across these cases, the pattern is consistent. When the Deed of Sale reflects reality, transactions move quietly and efficiently. When it doesn’t, the problems surface later—louder, costlier, and harder to fix.

Practical Deed of Sale Checklists and Best Practices

👉 Checklists don’t slow transactions—they prevent rewinds.

In Philippine real estate transactions, clarity beats memory. Checklists reduce risk not because they are complex, but because they force discipline at the exact points where mistakes usually happen. These are the checks that consistently separate smooth transfers from stalled ones.

Buyer Checklist

Before signing a Deed of Sale, buyers should confirm that the title is authentic, updated, and free from adverse annotations that affect ownership or use. Seller identity and authority must match the title and supporting documents exactly. For bank-financed purchases, loan approval and issuance of a Letter of Guarantee must already be in place. The Deed of Sale should declare full payment, align with the approved loan structure, and include clear warranties on title, taxes, dues, and possession. If any risk matters, it must appear in writing.

Seller Checklist

Sellers should verify that payment conditions are secured before execution—cleared funds for cash deals, approved loans and Letters of Guarantee for financed transactions. The Deed of Sale should limit post-sale liabilities, define turnover dates, and clearly allocate responsibility for taxes, utilities, and association dues. Tax classification must be confirmed early to avoid reassessment. Sellers should also ensure that title and documents are released only through a controlled, coordinated process.

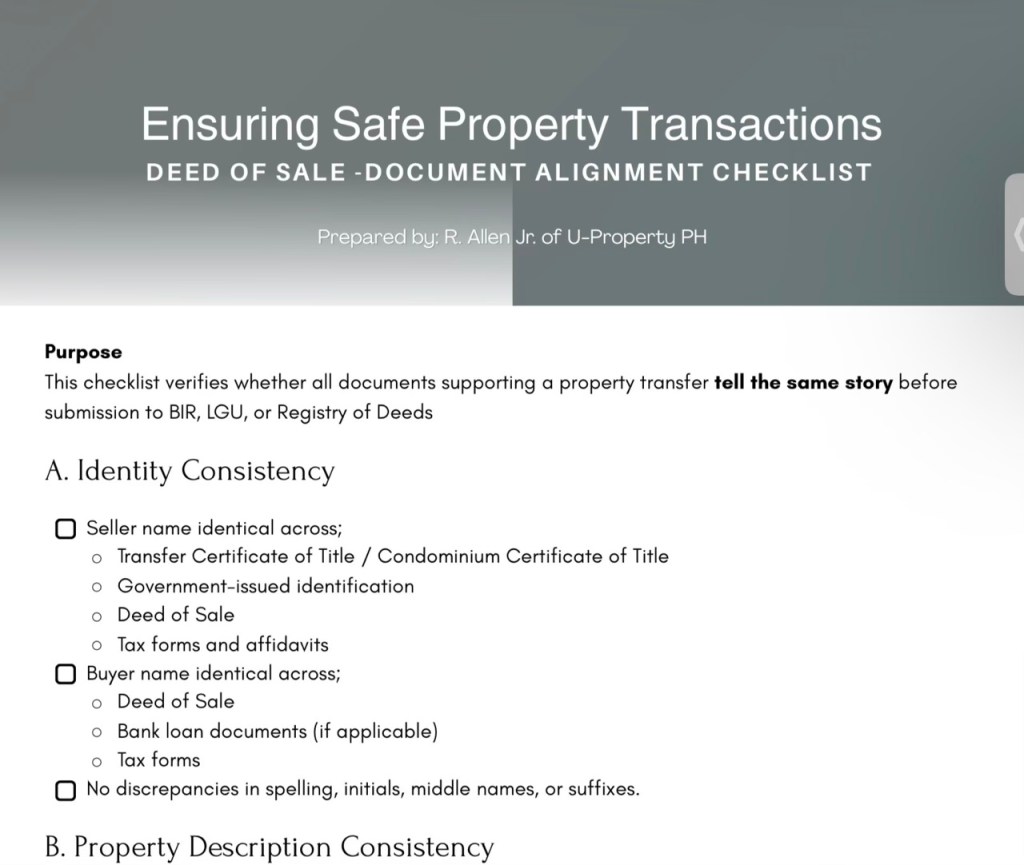

Document Alignment Checklist

Every document must tell the same story. Names, property descriptions, selling price, and transaction dates must be consistent across the Deed of Sale, title, tax declarations, bank documents, and payment records. Misalignment is the most common reason for BIR findings and Registry of Deeds rejections. If a correction is required, it should be made before notarization, not after.

Best practice is simple: if a document supports the transaction, it must support it consistently. Anything less invites delay.

The Deed of Sale as a Risk Management Tool, Not Paperwork

The Deed of Sale is often treated as the last document to sign when a deal feels “done.” In reality, it is the document that determines whether the deal will hold. Under Philippine practice, it sits at the intersection of private agreement and public record, and everything that follows—tax clearance, title transfer, loan release, resale—relies on its accuracy.

Strategically, a sound Deed of Sale does three things. It aligns the transaction with how payment actually occurs. It anticipates how government offices will assess and process the transfer. And it preserves the property’s future marketability. When these are ignored, the cost is not theoretical. It shows up as delayed titles, blocked resales, denied financing, or assets that cannot be cleanly passed on to heirs.

Long-term ownership value is not built at resale; it is locked in at acquisition. A property supported by a clean, defensible Deed of Sale remains liquid, financeable, and easy to exit. One supported by shortcuts becomes a holding problem disguised as an asset.

The discipline is clear. Treat the Deed of Sale as risk management, not paperwork—and most real estate problems never get the chance to start.

Verify Before You Sign a Deed of Sale

Most property problems don’t come from bad deals. They come from documents that were never pressure-tested.

Before you sign a Deed of Sale—whether you’re buying, selling, or investing—make sure it actually protects you, aligns with bank and registry requirements, and won’t block resale or title transfer later.

After notarization, fixing documents is no longer preventive—it’s corrective.

If you want a second set of experienced eyes on your transaction, you can:

- Request a Deed of Sale and document review before signing

- Book a property due diligence consultation for resale, estate, or bank-financed transactions

- Download a pre-signing checklist to validate your documents step by step

This is not about adding friction. It’s about removing future risk.

Leave a comment