A real estate transaction can collapse on one overlooked detail—and for many Filipinos, that detail is notarization. Every year, buyers lose millions, sellers face stalled transfers, and families inherit long-standing disputes because one document wasn’t notarized properly or wasn’t notarized at all. The belief that “basta may pirma, valid na yan” has undone countless property deals across the country.

A signature alone doesn’t protect you. A notarized document does.

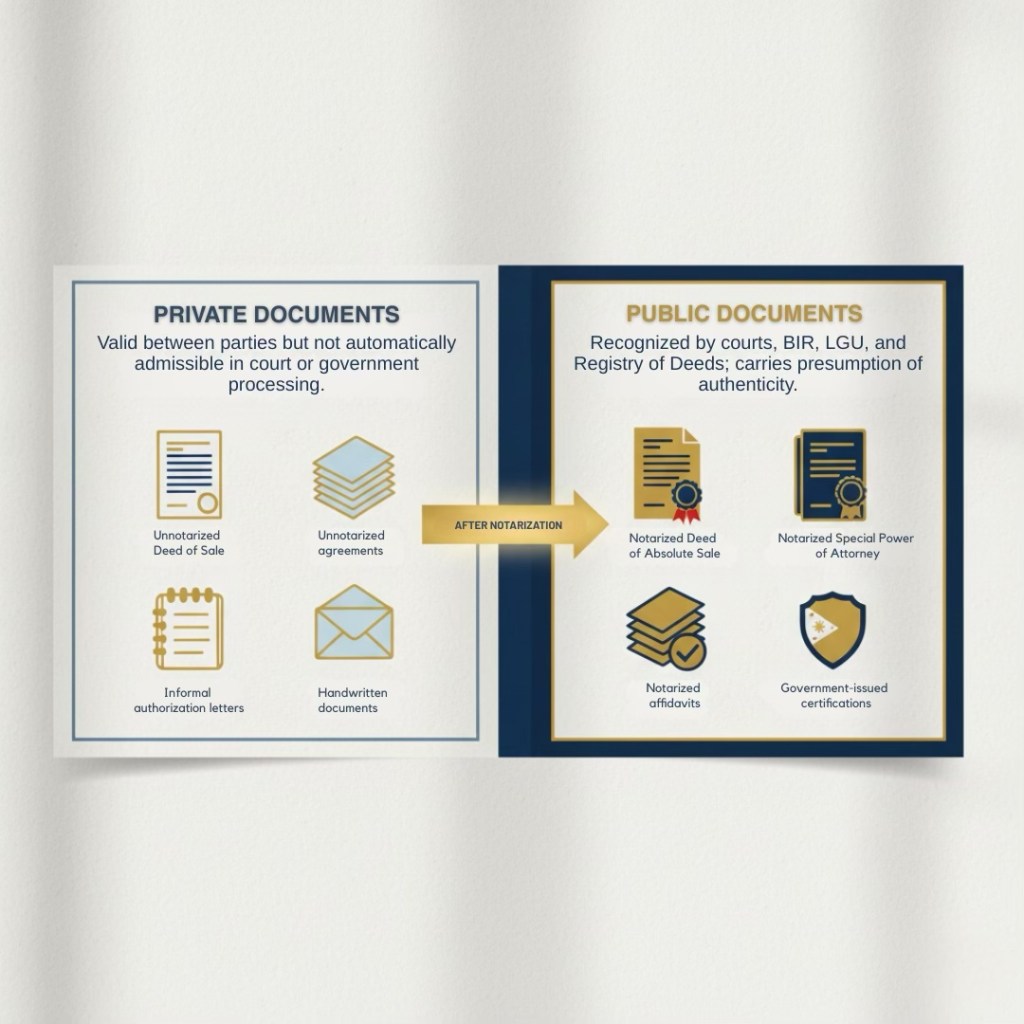

Notarization is not a decorative stamp or a routine formality. It transforms a private contract into a public document with legal weight, enforceable before government agencies, courts, and the Registry of Deeds. Without notarization, a Deed of Absolute Sale is just a private promise—powerful in intention but too weak for tax filing, loan processing, or title transfer.

This distinction is where costly misconceptions thrive. Many Filipinos still assume:

- That two signatures automatically create a binding sale

- That a relative can “sign on behalf” without a proper SPA

- That any lawyer can notarize anywhere

- That notarization only matters “later on,” once the transfer begins

Yet under Philippine law, only notarized real estate documents gain the presumption of authenticity required for ownership transfer. This is why banks, BIR, LGUs, and the Registry of Deeds refuse to process unnotarized or improperly notarized papers. And it’s why scammers exploit weak notarization—double selling, forged SPAs, impersonation, and fake sellers thrive when oversight is missing.

In a market where one mistake can delay a transaction for months—or derail it entirely—a Notary Public becomes more than a witness. They become the legal gatekeeper of the entire deal.

This guide breaks down the notary’s role, the documents that require notarization, the red flags to avoid, the risks of improper notarization, and the steps buyers, sellers, investors, and OFWs must follow to protect themselves and their property rights.

- What a Notary Public Really Does

- Why Notarization Matters in Real Estate Transactions

- Documents That Must Be Notarized (and Why)

- Legal Effects of a Notarized Document

- The Notarial Process Explained (Step-by-Step)

- Red Flags & Risks of Improper Notarization

- Best Practices for Buyers, Sellers & Real Estate Agents

- Preventing Fraud & Double Selling: The Notary’s Role

- Fees, Timelines & OFW-Specific Policies

- Case Studies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Key Takeaways

What a Notary Public Really Does

A Notary Public is often perceived as someone who simply stamps paper. In reality, they play one of the most critical roles in the entire Philippine real estate system. Every time a document is notarized, the notary is certifying that the people involved truly appeared, identified themselves correctly, and voluntarily agreed to what they signed. Their signature doesn’t just acknowledge a document—it transforms it into an instrument the law is willing to trust.

This is why a notary sits at the intersection of law, identity verification, and public protection. When the notarial process is done properly, real estate transactions become traceable, enforceable, and legally defensible. When it’s done improperly, the door opens to fraud, double selling, and years of litigation.

Legal Definition in PH

Under Philippine law, a Notary Public is a licensed lawyer commissioned by the Regional Trial Court to perform notarial acts. This authority comes from the 2004 Rules on Notarial Practice, which set strict standards for identity verification, documentation, record-keeping, and jurisdiction.

A legitimate notary must ensure:

- The signatories personally appear

- They present valid and competent IDs

- They sign the document voluntarily

- They understand the contents they are executing

- The document is complete and free of alterations

Once the notary affixes their signature and seal, the document becomes a public document, carrying strong legal credibility and presumptive authenticity.

This is why notarization is indispensable in real estate—no transaction involving property rights moves forward without it.

Authority Under the Rules on Notarial Practice

A Notary Public’s authority is both broad in responsibility and limited by law. Their legally recognized powers include:

- Acknowledgments → used for real estate documents such as DOAS, SPA, and contracts

- Jurats → used for affidavits and sworn statements

- Certifying copies of certain documents

- Performing protests and special notarial acts where allowed

However, this authority applies only within the territorial jurisdiction where the notary is commissioned. For example:

- A notary commissioned in Quezon City must notarize within QC.

- A notary commissioned in Cebu City cannot notarize in Mandaue.

Any act outside their jurisdiction can be declared void, even if the document looks perfectly notarized.

Notaries are also required to:

- Maintain a Notarial Register of every transaction

- Submit periodic reports to the court

- Follow strict documentary protocols

- Refuse notarization when irregularities arise

Their work is not administrative—it is a legal function bound by procedure, ethics, and accountability.

What Notaries Cannot Do

A notary’s authority has clear boundaries, and violating these rules can invalidate the document and expose the notary to penalties or disbarment.

A Notary Public cannot:

- Notarize without personal appearance

- Accept expired, questionable, or insufficient IDs

- Notarize outside their jurisdiction

- Notarize documents where they have a personal, financial, or professional interest

- Notarize for relatives up to the fourth civil degree

- Notarize blank, incomplete, or altered documents

- “Fix” errors, missing details, or unauthorized corrections

- Continue notarizing after their commission has expired or been revoked

If any of these conditions exist, the notarization becomes defective—no matter how official the stamp looks.

In real estate transactions, such defects cause most of the BIR and Registry of Deeds rejections buyers experience.

Common Misconceptions & Real-World Impact

Many Filipinos misunderstand what notarization actually does. These misconceptions lead to costly mistakes.

Misconception 1: “Basta may pirma, valid na yan.”

Reality: A private document has limited legal force. Without notarization, it’s often useless for enforcing rights or transferring ownership.

Misconception 2: “Pwede nang ipa-notaryo kahit wala ako.”

Reality: Personal appearance is mandatory. Violating this rule makes the document void—and the notary liable.

Misconception 3: “Any lawyer can notarize anywhere.”

Reality: A private document has limited legal force. Without notarization, it’s often useless for enforcing rights or transferring ownership.

Misconception 4: “Notarization means ownership is transferred.”

Reality: Notarization enhances validity but does not transfer ownership. Title transfer still requires taxes, CAR issuance, and ROD processing.

Real-World Consequences

When these misconceptions collide with real estate transactions, the fallout can be severe:

- BIR refusal to process taxes

- Registry of Deeds rejection

- Invalid SPAs leading to failed OFW transactions

- Double selling claims that favor the buyer with the notarized document

- Court disputes dragging on for years

Most property-related legal issues in the Philippines trace back to one culprit: improper or misunderstood notarization.

Why Notarization Matters in Real Estate Transactions

In Philippine real estate, nothing moves—not taxes, not bank loans, not title transfer—until documents pass through a Notary Public. It’s not bureaucracy for bureaucracy’s sake. It’s the legal system’s way of ensuring that every signature tied to millions of pesos is real, voluntary, and traceable. When a document is notarized properly, the entire transaction gains structure and legal certainty. When it’s not, the deal becomes vulnerable to fraud, impersonation, and government rejection.

Here’s what notarization accomplishes behind the scenes—and why skipping it is one of the costliest mistakes a buyer or seller can make.

Making Documents Legally Binding & Enforceable

A notarized document becomes a public document, which carries a powerful legal presumption: the signatures and the contents are authentic unless proven otherwise. That single shift—from private to public—changes everything.

With notarization:

- The document becomes self-authenticating.

- Courts treat it as prima facie evidence of a valid agreement.

- Government agencies accept it without further authentication.

- Parties gain legal enforceability in case of breach or dispute.

Without notarization, a Deed of Absolute Sale remains a private agreement—valid between the parties but practically useless for title transfer or tax filing. Banks, BIR, and the Registry of Deeds simply will not honor it.

This is why real estate contracts must be notarized before they can trigger ownership, authority, or possessory rights.

Authenticating Identity of Parties

Identity verification is the notary’s first line of duty—and one of the most important protections in real estate.

Before notarizing, the notary must:

- Examine government-issued IDs

- Ensure the signer personally appears

- Confirm voluntariness and full understanding

- Verify signatures and compare them to IDs

- Ask clarifying questions when necessary

This process eliminates common threats:

- People impersonating the owner

- Relatives selling property without authority

- Brokers posing as representatives

- Buyers claiming later they “never signed anything”

Notarization forces identity accountability. It validates who signed and when, creating a legal timestamp that becomes crucial when disputes arise.

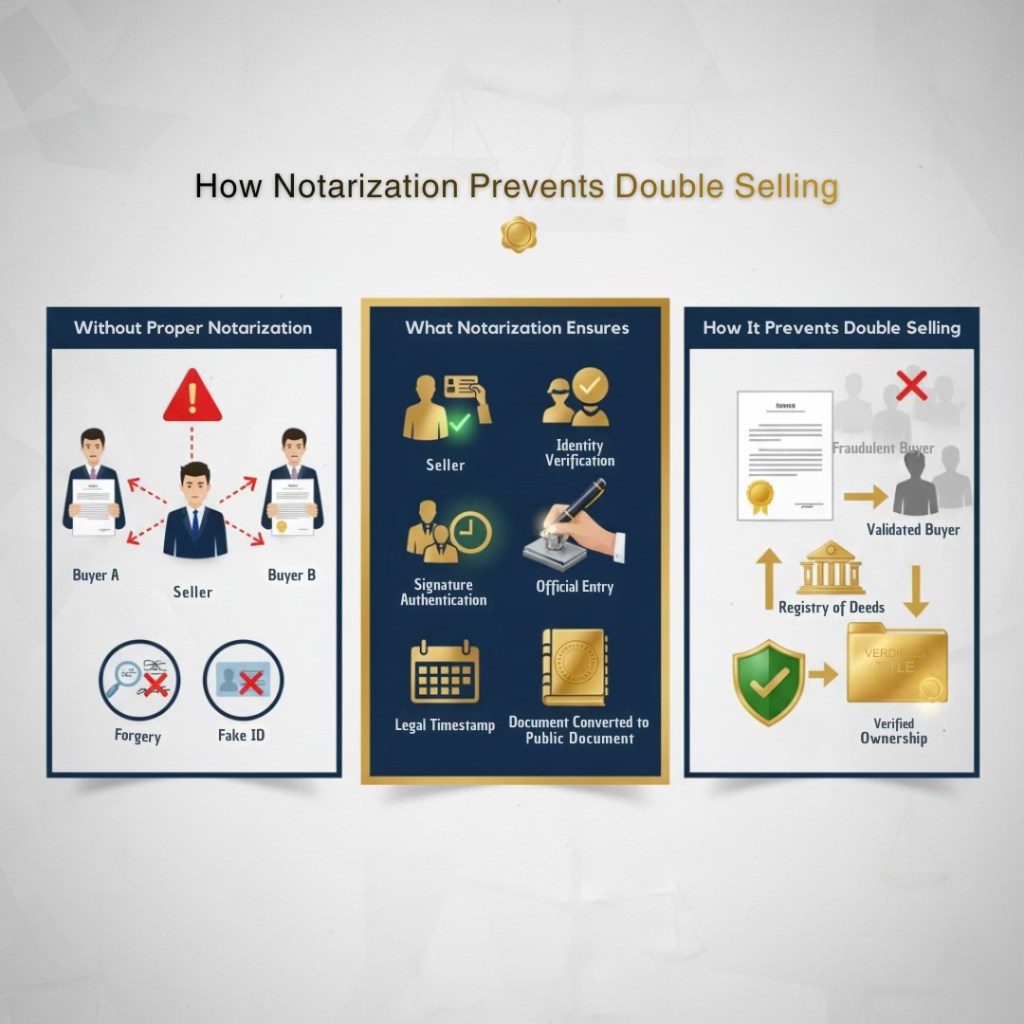

Preventing Fraud, Impersonation, and Double Selling

Real estate fraud thrives in the shadows—informal signings, rushed documents, or “paki-notaryo na lang” shortcuts. A proper notarization removes those shadows completely.

A legitimate notary helps prevent:

- Double selling by creating a documented timeline

- Impersonation through strict ID and appearance rules

- Signature forgery by requiring verification

- Authority abuse (fake SPAs, unauthorized relatives signing)

- Document tampering, since notarized pages are sealed and logged

In many high-profile Philippine property disputes, courts found one common denominator: the fraudulent party relied on improperly notarized—or entirely unnotarized—documents.

Fraud collapses quickly when forced into the light of a proper notarial process.

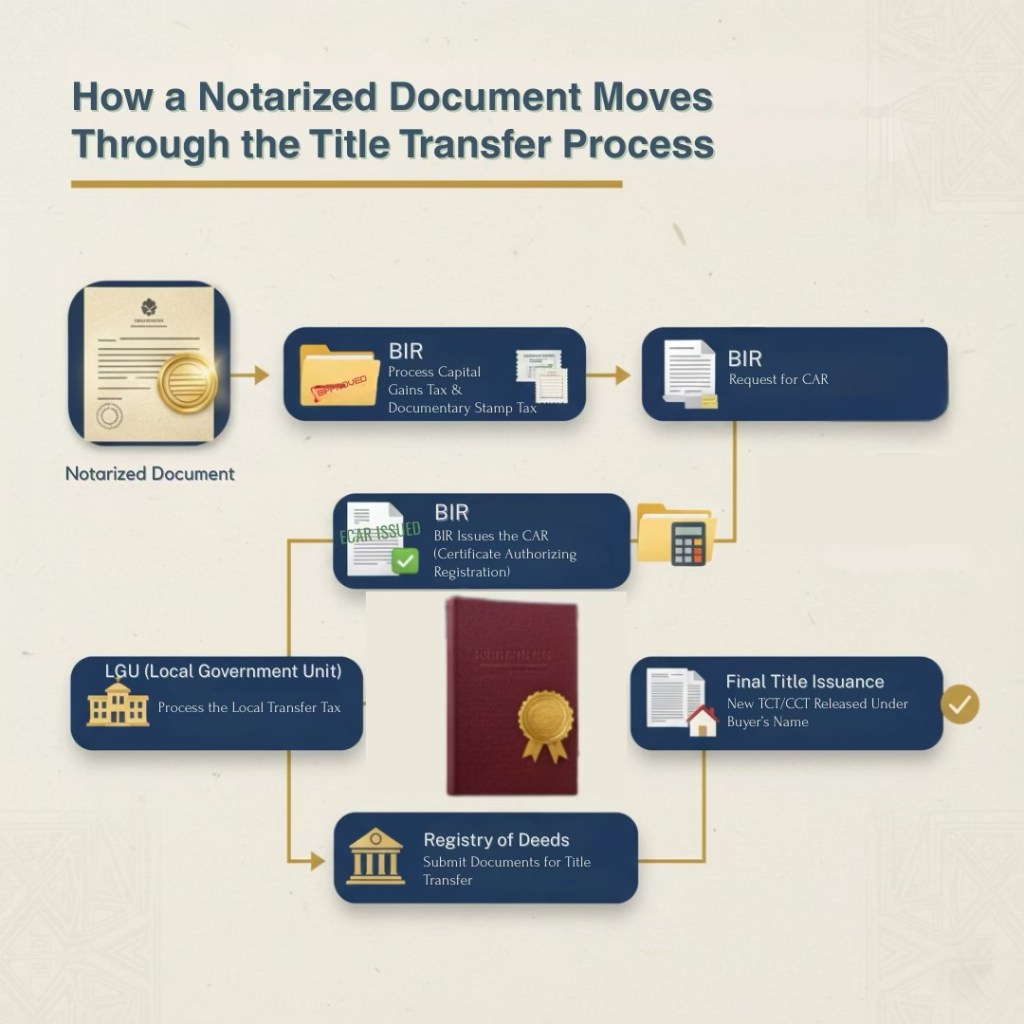

Required for Government Processing (BIR, ROD, LGU)

Notarization is not optional for real estate transactions—it’s a legal and administrative gateway. Government agencies rely on notarized documents because they carry the presumption of authenticity.

Here’s what notarization unlocks:

BIR (Bureau of Internal Revenue):

Before computing Capital Gains Tax (CGT) or Documentary Stamp Tax (DST), BIR requires a notarized DOAS. No notarization, no CAR.

Registry of Deeds:

They will not transfer the title unless the DOAS and supporting affidavits are notarized correctly and verified in the notarial registry.

LGU Requirements:

Cities and municipalities often require notarized certifications for tax clearance, zoning, and RPT updates.

Banks and Lenders:

Loan takeout, CTS validation, and SPA acceptance all hinge on notarization.

Put simply:

You cannot move past Step 1 of title transfer without notarized documents

Why Courts Give More Weight to Notarized Documents

When a property dispute reaches court—a forged signature, an impersonated seller, a contested waiver—the court turns to one crucial question:

Which document carries the presumption of regularity?

A legitimate notary helps prevent:

- Double selling by creating a documented timeline

- Impersonation through strict ID and appearance rules

- Signature forgery by requiring verification

- Authority abuse (fake SPAs, unauthorized relatives signing)

- Document tampering, since notarized pages are sealed and logged

In many high-profile Philippine property disputes, courts found one common denominator: the fraudulent party relied on improperly notarized—or entirely unnotarized—documents.

In real estate disputes involving double selling, forged SPAs, or questioned waivers, the notarized document almost always becomes the decisive factor. It is considered reliable unless proven otherwise, and proving otherwise is extremely difficult.

This is why notarization is not just a procedural step—it’s a strategic legal safeguard.

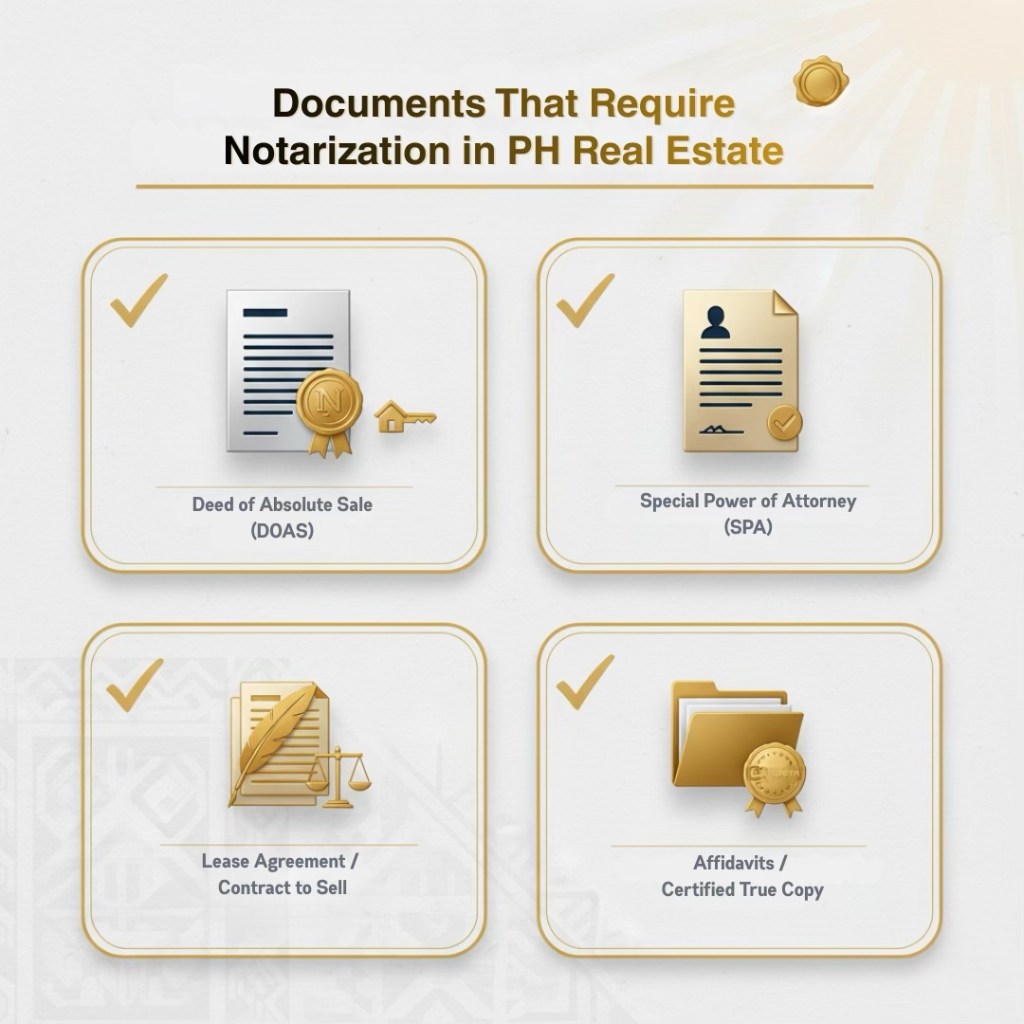

Documents That Must Be Notarized (and Why)

Real estate transactions run on documents—proof of ownership, proof of authority, proof of payment, proof of intent. But these documents only carry legal weight once notarized. Notarization is what elevates a piece of paper into a public instrument that government agencies, banks, and courts can act on. Without this transformation, even a perfectly written contract will stall your transaction.

Below are the core Philippine real estate documents that must be notarized, why each matters, and how notarization protects the parties from fraud, rejection, and costly delays.

Deed of Absolute Sale (DOAS)

The DOAS is the heart of every property sale—the document that formally transfers ownership from seller to buyer. But it only gains legal force once notarized.

Why notarization is essential:

- It converts the DOAS into a public document, making it valid for BIR, LGU, and Registry of Deeds processing.

- It establishes a verifiable legal timestamp, crucial in double-selling cases.

- It confirms that both parties actually appeared, agreed voluntarily, and proved their identities.

- It ensures government agencies can rely on the document without additional authentication.

Without notarization, the DOAS is just a private agreement, powerless to initiate title transfer. The buyer’s payment—even if fully settled—does not legally shift ownership. The property remains under the seller’s name until the notarized DOAS reaches BIR and ROD.

No notarization, no transfer. It’s that simple.

Special Power of Attorney (SPA) — especially for OFWs

The SPA gives someone legal authority to sign and transact on your behalf—critical for OFWs and buyers or sellers who cannot appear in person.

Notarization is mandatory because:

- Agencies will reject any SPA that is not notarized, consularized, or apostilled.

- A representative cannot sign the DOAS, bank documents, or tax forms without a valid, notarized SPA.

- An improperly notarized or unauthenticated SPA can invalidate the entire sale.

For OFWs:

- The SPA must be consularized at a Philippine Embassy/Consulate or

- Apostilled if executed in a Hague Convention country.

A handwritten authorization, scanned signature, or “paki-represent na lang” instruction has zero legal value—and is often the root of failed transfers and scams.

Contract to Sell / Reservation Agreements

These early-stage documents are common in preselling projects, but they gain real power once notarized.

A notarized CTS or reservation agreement:

- Strengthens the buyer’s financial and legal protection

- Helps secure bank financing

- Establishes clearer obligations and deadlines

- Proves payment commitments and project deliverables

- Provides enforceability if disputes arise over turnover or unit specs

Developers often require notarized updates as payments progress. Skipping notarization weakens the buyer’s leverage when major issues occur.

Lease Agreements

A lease contract can be valid even without notarization—but notarizing it dramatically increases its enforceability and operational usefulness.

A notarized lease allows:

- Faster resolution of tenant disputes

- Stronger backing for eviction or collection cases

- Use in barangay or police complaints

- Proof of income for banks or government documentation

- Clear evidence of agreed rent, terms, and conditions

For landlords building passive income portfolios, notarization is a low-cost safeguard that prevents major headaches later.

Affidavits: Loss, Undertaking, Waiver, Non-tenancy

Affidavits play supporting roles in nearly every property transaction. They clarify intent, certify conditions, or fill in procedural gaps—but they only carry weight when notarized.

Common affidavits include:

- Affidavit of Loss – required when original documents are missing (TCT/CCT, receipts, tax declarations).

- Affidavit of Undertaking – binds the party to fulfill pending requirements or submit missing documents.

- Affidavit of Waiver – relinquishes rights, often used in inheritance cases or right-of-redemption scenarios.

- Affidavit of Non-Tenancy – certifies the property is vacant and free from illegal occupants.

Government agencies do not accept unnotarized affidavits.

Courts assign them little to no evidentiary weight.

In some disputes, the notarized affidavit becomes the deciding factor.

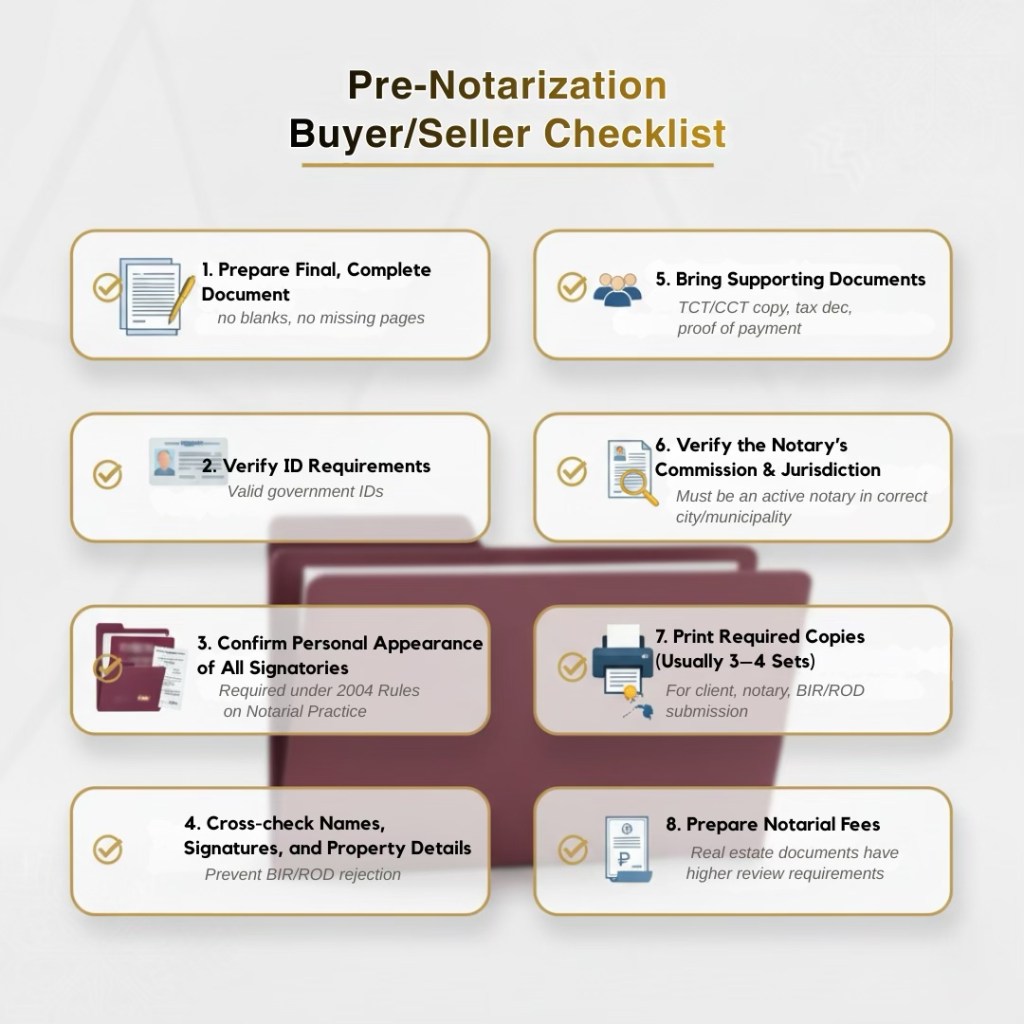

Notarization Requirements Checklist

A successful notarization relies on complete preparation. Missing documents or inaccurate details can delay the sale or, worse, invalidate the signing.

Here’s a refined, more buyer-friendly checklist:

✔ Mandatory Personal Appearance of All Signatories

No appearance = invalid notarization.

No exceptions—not even for relatives, brokers, or “trusted representatives.”

✔ Bring Valid Government-Issued IDs (Preferably Two)

IDs must be original, unexpired, and contain your photo and signature.

Common acceptable IDs:

- National ID (PhilSys)

- Passport

- Driver’s License

- UMID

- PRC ID

✔ Ensure Documents Are Final and Error-Free

Check for:

- No blank spaces

- No missing pages

- No erasures unless countersigned

- Correct spelling of names

- Accurate property details

- Proper pagination

✔ Prepare Supporting Documents (If Required)

These help the notary validate the transaction:

- Certified True Copy of Title

- Tax Declaration

- Proof of payment

- Developer-issued forms

- SPA or Board Resolution (if signing for a company or another person)

✔ Prepare Multiple Copies

Most notaries require at least three copies:

- One for the notary’s register

- One for the party

- One for BIR/ROD processing

✔ Payment of Notarial Fees

Fees vary by city, complexity, and law office reputation.

Expect higher rates for multi-page or high-value property documents.

Being thorough at this stage prevents costly BIR rejections and Registry of Deeds delays later.

Legal Effects of a Notarized Document

A notary’s seal does more than decorate a page—it activates a document’s legal power. Once notarized, a real estate contract becomes far more difficult to dispute, easier to enforce, and fully acceptable to government agencies. Failing to notarize—or notarizing incorrectly—can immobilize a transaction instantly. Understanding the legal transformation that notarization triggers is essential for buyers, sellers, investors, and OFWs.

Conversion of Private Doc → Public Doc

Before notarization, even the most carefully written Deed of Sale is just a private document—binding between the parties but weak in legal and administrative power.

After notarization, it becomes a public document, which means:

- Courts assume it is authentic and executed voluntarily

- Government agencies accept it without requiring additional proof

- Banks treat it as a valid contractual instrument

- It becomes legally enforceable and admissible as evidence

This transformation is what enables:

- BIR to compute taxes

- LGUs to issue clearances

- Registry of Deeds to approve a title transfer

No notarization = no transition from private agreement to real ownership.

Presumption of Regularity in Court

The Philippine justice system grants notarized documents a powerful legal advantage: the presumption of regularity.

Courts automatically assume:

- The identities of signatories were properly verified

- The signatures are genuine

- The parties understood and freely agreed to the contract

- The notary complied with the Rules on Notarial Practice

This presumption shifts the burden of proof.

The challenger—not the party presenting the notarized document—must prove fraud or irregularity. And that is an extremely high bar.

When property disputes arise, the notarized document becomes the anchor that stabilizes the case. Unnotarized documents rarely survive courtroom scrutiny.

Required for Tax Filing and Title Transfer

Real estate transfers cannot progress without notarized documents. Government offices rely on notarization to establish authenticity and to ensure no fraud is taking place.

BIR Requirements:

A notarized DOAS is required before BIR can:

- Compute Capital Gains Tax (CGT)

- Compute Documentary Stamp Tax (DST)

- Issue the Certificate Authorizing Registration (CAR)

Supporting documents like SPAs and affidavits must also be notarized.

Registry of Deeds Requirements:

The ROD will not transfer a title unless:

- The DOAS is properly notarized

- Notarial details match the notary’s commission

- The notarial register entry is verifiable

Any defect—even a mismatched seal—halts the transfer immediately.

LGU Requirements:

LGUs and city assessors often require notarized documents for:

- Real Property Tax (RPT) updates

- Zoning certifications

- Business permit applications (for rental properties)

In real estate, notarization isn’t a formality—it’s a checkpoint that unlocks every succeeding step.

What Happens if a Document Is Not Notarized

Skipping notarization creates a legal dead-end. Even if both parties agree fully and payment has been completed, the transaction cannot move forward.

Consequences include:

- Title cannot transfer at the Registry of Deeds

- BIR will not compute taxes or issue CAR

- Banks reject the document for loan takeout or collateral

- Courts treat the document as weak evidence

- Property remains under the seller’s name, regardless of payment

- Increased vulnerability to fraud, especially double selling

In other words:

An unnotarized sale is not a completed sale. It’s an unfinished promise.

Buyers often discover this too late—sometimes months into the transfer process.

Cases of Title Denial due to Unnotarized DOAS

Many title transfer failures stem from mistakes in notarization—not from problems with the parties themselves. These scenarios occur regularly across BIR offices and Registries of Deeds nationwide:

BIR Rejection Scenarios

- DOAS not notarized at all

- Notary’s commission expired during notarization

- Incorrect notarization format

- Notarial seal missing or mismatched

- SPA used without proper notarization, apostille, or consular authentication

BIR examiners will not process CGT or DST if any notarial detail is questionable.

Registry of Deeds Refusal

- Notarization done outside the notary’s jurisdiction

- Notarial entries inconsistent with the notarial register

- Signatory did not appear personally (ROD may require verification)

- Witnesses or annexes missing

Any inconsistency prompts immediate denial.

Disputes Triggered by Unnotarized or Defective DOAS

- Competing buyers in double-selling cases—courts favor the notarized version

- Inheritance disputes where heirs present conflicting documents

- OFW transactions invalidated because foreign SPAs lacked apostille or consular seals

Real estate is unforgiving. One technical error can take months—sometimes years—to repair.

Notarized vs. Unnotarized Deed of Sale

| Category | Notarized Deed of Absolute Sale | Unnotarized Deed of Absolute Sale |

|---|---|---|

| Legality | Considered a public document under the Civil Code and the 2004 Rules on Notarial Practice; carries presumption of authenticity; legally enforceable against third parties. | Treated only as a private document; valid between the parties but has weak evidentiary value and no presumption of authenticity. Cannot be used to effect transfer of ownership. |

| Court Treatment | Courts recognize it as prima facie evidence of a valid sale. Signatures, consent, and identity are presumed genuine unless proven otherwise (Rule 132, Sec. 30–31). | Court requires additional proof of execution and authenticity. Easily challenged; may be inadmissible as evidence without proper authentication. |

| BIR Acceptance | Required for computation of Capital Gains Tax (CGT) and Documentary Stamp Tax (DST). BIR will not issue a CAR without a notarized DOAS (per BIR Revenue Regulations 13-99, 18-2003). | Automatically rejected. CGT and DST cannot be assessed; CAR cannot be issued. Tax clearance processing cannot begin without notarization. |

| Registry of Deeds Acceptance | Fully acceptable for title transfer under the Property Registration Decree (PD 1529) because it is a public instrument. Must include notary details consistent with the notarial register. | Rejected by ROD. Title transfer cannot proceed. ROD requires notarized DOAS as a public instrument before changing ownership in the TCT/CCT. |

| Overall Impact | Enables full legal transfer of ownership. Protects both buyer and seller. Provides clear timeline of execution and protects against fraud and double selling. | Prevents title transfer, delays or voids the sale, and increases fraud risk. Buyer has no enforceable claim to the property despite payment. Transaction remains incomplete and vulnerable. |

The Notarial Process Explained (Step-by-Step)

Most Filipinos imagine notarization as a quick pit stop: sign the paper, get a stamp, go home. But in real estate, notarization is a legal procedure with strict standards, designed to prevent fraud, validate identity, and protect millions of pesos in property value. Understanding the process helps buyers, sellers, and OFWs avoid delays—and ensures documents won’t be rejected by BIR, banks, or the Registry of Deeds.

Below is a refined, real-world breakdown of how notarization actually works in the Philippines.

Preparing the Document

A notary cannot—and legally must not—notarize a document that is incomplete, incorrectly formatted, or unclear. The document must reach the notary in final form, error-free and ready for signing.

A document is NOT ready for notarization if it has:

- Blank fields

- Missing attachments or missing pages

- Inconsistent names or mismatched ID details

- Erasures or handwritten corrections not properly countersigned

- Inaccurate property descriptions (TCT number, lot area, address)

Proper preparation includes:

- Verifying all names against valid IDs

- Matching property details with the title and tax declaration

- Ensuring amounts, payment terms, and dates are accurate

- Printing multiple clean copies for stamping and filing

In real estate, even a single misplaced middle initial can derail a BIR filing. Document preparation is not paperwork—it’s risk prevention.

Personal Appearance Requirements

Personal appearance is the cornerstone of lawful notarization.

It is not a suggestion. It is a strict legal requirement.

Every signatory must appear before the notary to:

- Declare that they voluntarily executed the document

- Confirm that the signature is theirs

- Present valid government-issued identification

- Answer verification questions to establish understanding and consent

Personal appearance is mandatory because it prevents:

- Impersonation

- Coercion

- Signature forgery

- Unauthorized representatives signing on behalf of owners

For OFWs, personal appearance must take place before a Philippine Consulate or through apostille authentication—signing at a foreign notary alone is not enough.

If the signer does not appear, the notarization is legally defective and can be rendered void.

ID & Signature Verification Steps

A notary’s job is not to “stamp and go.” Their real duty is to verify identity and protect both parties from fraudulent transactions.

It is not a suggestion. It is a strict legal requirement.

Notaries must check:

- Original, unexpired government IDs

- Photo likeness

- Matching signatures

- Consistency of names (including middle initials)

- Possible red flags: altered IDs, suspicious behavior, mismatched details

A notary is required to reject a document when:

- IDs appear forged or altered

- Details don’t match the document

- The signer cannot answer basic verification questions

- There is doubt about mental capacity or voluntariness

This step is why notarization carries such weight—identity verification is baked into the legal process.

What Happens During Notarization Itself

Once identity is verified and the document is ready, the notary performs a sequence of formal steps. These steps ensure the act complies with the Rules on Notarial Practice.

The notary will:

- Witness the signing, or if the document was already signed earlier (acknowledgment), confirm that the signer indeed executed it voluntarily.

- Confirm identification using competent evidence.

- Administer the acknowledgment or jurat, depending on document type.

- Sign and affix the notarial seal, which contains the notary’s commission details.

- Record the transaction in the Notarial Register, including:

- Names and IDs of signatories

- Document title and description

- Date and time of notarization

- Notarial act performed

- Fees collected

- Provide stamped copies to the parties.

The moment the notary signs and seals the document, it becomes a public document—elevated in credibility and enforceability.

Fees, Timelines & What Buyers Should Expect

Notarial fees vary, but higher-value real estate documents typically cost more due to legal risk and administrative scrutiny.

Typical fees:

- Affidavits: ₱150–₱500

- SPAs: ₱500–₱1,500

- DOAS / CTS / Real estate contracts: ₱1,000–₱2,500+

- Corporate or multi-party transactions: ₱2,500–₱5,000+

Premium business districts (BGC, Makati, Ortigas) often have higher rates due to professional overhead and higher liability exposure.

Timelines:

- Simple affidavits: 5–10 minutes

- SPAs and real estate contracts: 15–30 minutes

- Multi-signer, multi-page documents: 30–60 minutes

Expect the notary to require:

- Original IDs

- All signatories present

- Complete, final documents

- Supporting proof (title copy, developer docs, payment receipts)

- Multiple copies for recording and release

A good notary is not slow—they’re thorough.

Digital / E-Notarization: What’s Allowed in the Philippines?

Despite the rise of online tools, the Philippines still does not allow remote or online notarization for real estate documents. Real estate is too high-risk, and identity verification requires personal appearance.

Current rules:

- Physical personal appearance is mandatory for DOAS, SPA, CTS, leases, and affidavits.

- Electronic or video notarization is not recognized for property documents.

- E-signatures (DocuSign, Adobe Sign) do not replace notarization.

- OFWs must follow:

- Consular notarization (Philippine Embassy/Consulate), or

- Apostille authentication in Hague Convention countries

What is allowed digitally?

Some courts have allowed limited e-notarization during emergencies, but not for real estate. The law remains strict for property documents due to their high value and risk of fraud.

This means:

If you are signing a Deed of Sale or SPA, you must appear before a notary or proper foreign authority—no shortcuts.

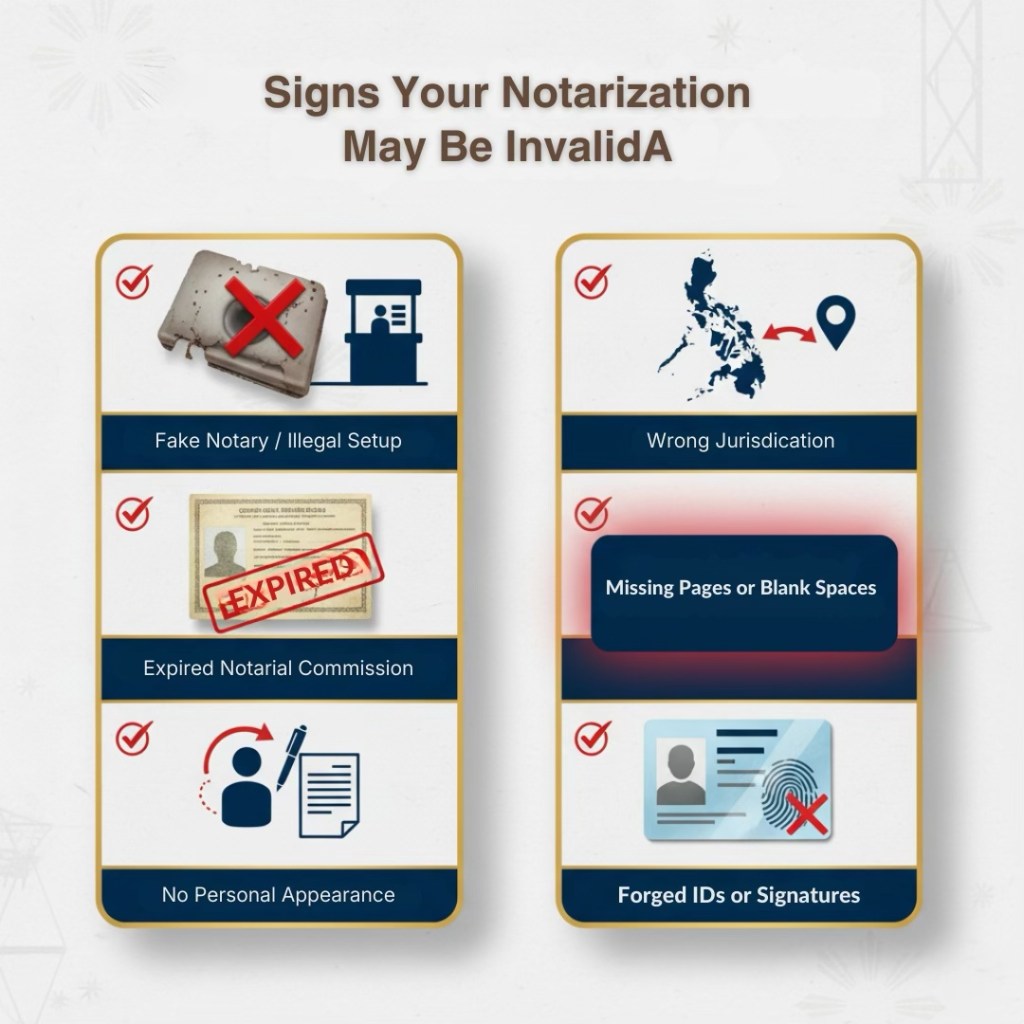

Red Flags & Risks of Improper Notarization

When notarization is done correctly, it becomes your strongest shield in a real estate transaction. When it’s done improperly—or worse, fraudulently—it becomes a trap. Buyers lose millions, sellers face lawsuits, OFWs get scammed, and transactions collapse under scrutiny at the BIR or Registry of Deeds.

These red flags are not theoretical. They appear every week across the Philippines, often in the exact situations ordinary buyers and first-time sellers encounter. Recognizing them early is how you prevent real estate disasters.

Fake Notaries (“Backroom or Bathroom Notaries”)

Improper notarization often starts with the wrong notary—usually one operating where a legitimate law office would never exist.

Fake notaries typically:

- Operate inside photocopy shops, mall stalls, or cramped kiosks

- Charge impossibly low fees (₱50–₱100)

- Do not ask for IDs or require personal appearance

- Use expired, borrowed, or fabricated seals

- Notarize documents in bulk without checking content

Documents from these operators are void, and using them exposes you to serious consequences:

- Immediate BIR rejection

- Title transfer refusal

- Accusations of participating in fraud

- Court challenges that can drag for years

Rule of thumb:

If the place looks informal, the notarization will be invalid.

Expired Commissions

Every Notary Public is commissioned for a fixed term. If they notarize documents after their commission expires, all notarized documents during that period become invalid—no matter how “official” they look.

Common signs of an expired or invalid notary commission:

- The seal indicates a past year

- The commission certificate is missing or not displayed

- The notary avoids questions about jurisdiction or validity

- The office setup doesn’t match a professional law practice

An expired commission means:

- BIR cannot process taxes

- Registry of Deeds cannot issue a new title

- Courts will strike down the document if challenged

One overlooked detail can reset your entire transaction.

Notaries Working Outside Their Jurisdiction

A notary’s authority is restricted to a specific city or municipality. This is one of the most common causes of BIR and ROD rejection.

Examples:

- A Quezon City–commissioned notary notarizing in Makati

- A Pasig notary operating from an office in Mandaluyong

- A provincial notary notarizing documents in NCR

If notarization happens outside the authorized territory, the document becomes voidable and vulnerable to challenge—even years later.

Agencies check jurisdiction strictly because it protects the integrity of public documents. If the venue on the document does not match the notary’s commission, it’s a hard red flag.

Notarization Without Personal Appearance (VOID)

This is the most common—and most dangerous—violation in Philippine transactions.

Any notarization done without the signer physically appearing before the notary is invalid.

Improper practices include:

- Sending documents via messenger for stamping

- Signing at home and asking the notary to “just seal it later”

- Brokers or relatives representing the signer without a valid SPA

- OFWs signing documents abroad with no apostille or consular seal

- “Drop-off notarization” done by informal fixers

These shortcuts create void notarization, exposing you to:

- Title transfer denial

- BIR rejection

- Claims of forgery

- Criminal liability for the notary—and sometimes the parties

If you did not appear in front of the notary, the document is already compromised.

Forged IDs and Impersonation Cases

Identity fraud is alarmingly common in Philippine real estate. This is why the notary must verify the signer’s identity meticulously. But when someone circumvents the process, the risk skyrockets.

Common impersonation cases include:

- A relative pretending to be the seller

- Someone using a fake or tampered ID

- A buyer represented by a non-authorized individual

- Heirs forging signatures to sell inheritance property

- Unauthorized persons submitting forged SPAs for OFW-owned homes

Improper notarization makes it far easier for impostors to slip through, because the notary never performed the required screening.

Once impersonation occurs, the damage is immediate and severe:

- Ownership becomes disputed

- Buyers lose money

- Sellers face legal threats

- OFWs learn too late that someone sold their land without consent

A legitimate notary is the gatekeeper meant to stop this. When the process is bypassed, fraud takes over.

How These Lead to Double Selling or Court Battles

Improper notarization doesn’t just “cause delays.” It ignites full-blown legal disasters.

Double Selling

If the DOAS is unnotarized or notarized improperly:

- The seller can resell the property to someone else

- The second buyer may secure a valid notarized document

- Courts will favor the notarized buyer

Result:

The first buyer loses the property—even if they paid in full.

BIR Denials

BIR examiners reject defective documents immediately. Consequences include:

- Delayed tax payments

- Accrued penalties and surcharges

- Postponed CAR issuance

Without CAR, title transfer is frozen.

Registry of Deeds Rejections

ROD is extremely strict. They refuse documents for:

- Wrong jurisdiction

- Missing seal elements

- Suspicious notary commission details

- Unverified notarization entries

A single defect pushes you back to Step 1.

Court Battles Lasting Years

Improper notarization becomes a litigation breeding ground:

- Heir disputes

- Buyer vs seller complaints

- OFW family fraud cases

- Multi-buyer ownership claims

Real estate litigation in the Philippines can last from 2 to 15 years.

Most of these wars could have been avoided with one thing: proper notarization.

Best Practices for Buyers, Sellers & Real Estate Agents

Notarization is the gatekeeper of a valid real estate transaction. When handled correctly, it protects everyone involved—buyers securing their investment, sellers preserving their rights, and agents facilitating a smooth and professional closing. When done sloppily, a single missed detail can derail months of work, freeze the title transfer, or expose parties to fraud.

Below are the essential steps every party should follow before, during, and after notarization.

Verifying if a Notary is Legitimate

Not all offices offering “notary services” are authorized to notarize real estate documents. Many are uncommissioned, expired, or under suspension—yet still operate. A legitimate notary is non-negotiable.

How to verify a legitimate Notary Public:

Check the Notarial Commission Certificate

Must be displayed prominently in the office and indicate:

- Valid commission year

- Roll number

- Commission number

- Territorial jurisdiction

Inspect the Notarial Seal

It should match the commission and include the notary’s:

- Full name

- Roll and commission number

- City or municipality of commission

Confirm the Office Location

Legitimate notaries typically operate inside:

- Law offices

- Established firms

- Professional legal service hubs —not photocopy stalls, mall kiosks, or barangay-level booths.

Cross-check with the RTC (Regional Trial Court)

You can request confirmation that the notary is:

- Currently commissioned

- Authorized within that jurisdiction

A legitimate notary minimizes risk, strengthens your documents, and ensures the notarization will withstand scrutiny at BIR or the Registry of Deeds.

Preparing Complete Documentation

BIR and ROD examiners reject documents for even minor inconsistencies. Preparation is not “extra work”; it is critical due diligence.

Before meeting the notary, ensure you have:

✔ Final, error-free document

Check spelling, middle initials, property details, TCT number, page numbers, and monetary amounts.

✔ At least three clean printed copies

Notaries will retain one copy for their register.

✔ Two valid, government-issued IDs per signatory

Must be original, unexpired, and consistent with the document details.

✔ Required supporting documents, such as:

- Certified True Copy of Title

- Updated Tax Declaration

- Extract from developer for new condos

- Proof of payment or receipts

- SPA or board resolution if representing someone

✔ Consistent signatures

Signatures must match the IDs. Government offices reject documents with mismatched or suspicious signatures.

Treat document preparation the same way you treat money—handle it carefully.

Avoiding Common Errors That Lead to Rejection

These mistakes derail more real estate transactions than anything else. All of them are avoidable.

Major red flags that prompt instant BIR or ROD rejection:

- Misspelled names or incorrect middle initials

- ID details not matching the document

- Blank spaces left in any part of the form

- Missing annexes or missing pages

- Uncountersigned erasures or handwritten edits

- Notary signatures placed on the wrong page

- Venue and notarial details not matching the notary’s commission

- Documents notarized without personal appearance

- Outdated or invalid notarization formats

- Improper apostille or consular authentication for OFW documents

Once the document is rejected, you restart the entire cycle, losing weeks or months.

Avoid these errors and you avoid the most painful part of real estate transactions: do-overs.

Why Agents Should Review Documents Before Notarization

Real estate agents are often the first line of defense against errors. A thorough review positions the agent as a trusted professional—not just a messenger.

Agents should check:

✔ Accuracy of names, ID details, and property descriptions

- TCT/CCT

- IDs

- Tax Declaration

- Developer documents

✔ Completeness of all pages and annexes

A missing page is grounds for immediate ROD rejection.

✔ Correct SPA format for OFWs

Agents must ensure SPAs are consularized or apostilled—not just notarized abroad.

✔ Consistency of signatures

A missing page is grounds for immediate ROD rejection.

✔ Whether the notary’s jurisdiction aligns with the document venue

This single oversight can invalidate the entire DOAS.

A proactive agent prevents disputes and elevates the integrity of the entire transaction. Clients remember agents who save them from costly paperwork mistakes.

How to Secure Certified Copies After Notarization

Notarization is not the end—it’s the beginning of document processing. Certified copies provide additional layers of protection and convenience.

How to properly secure certified copies:

Request certified true copies from the notary immediately

hese should include:

- “Certified True Copy” annotation

- Notarial seal

- Notary’s signature

Ensure all pages carry appropriate seals or initials

BIR and ROD check for tampering.

Store digital scans securely

Useful for pre-screening, due diligence, and emergency reference.

Prepare separate copies for:

- BIR filing

- Bank loan processing

- Developer processing

- Personal records

Certified true copies help in disputes, protect against loss, and streamline government processing. They are small safeguards that prevent big problems.

Preventing Fraud & Double Selling: The Notary’s Role

Real estate fraud happens where documentation is weak. Impersonators slip through when no one checks IDs. Double selling thrives when there’s no official timeline of ownership. Fake sellers succeed when authority is not verified. Every major fraud pattern in the Philippine market has one thing in common: a document that was not properly notarized.

A legitimate Notary Public is not a mere witness. They are the system’s first security checkpoint—tasked with blocking scammers, validating identities, and ensuring that every agreement in a multi-million-peso transaction is genuine, voluntary, and enforceable.

Below is a refined breakdown of how proper notarization prevents the most common and most costly forms of real estate fraud.

Identity Verification and Signature Security

Fraudsters survive on anonymity. Notaries eliminate that advantage.

How to verify a legitimate Notary Public:

A legitimate notary performs strict identity checks before a single signature is accepted:

- Verifies original, unexpired government IDs

- Confirms facial likeness and signature patterns

- Ensures the signer personally appears

- Asks probing questions that reveal hesitation or inconsistency

- Rejects suspicious IDs, aliases, and mismatched details

This prevents:

- Fake heirs claiming ownership

- Relatives selling a property they do not own

- Syndicates posing as the seller

- Unauthorized “representatives” signing without authority

- Buyers denying their own signatures during disputes

Notaries convert signatures from mere ink into verified, traceable acts. And in litigation, that difference is everything.

Protecting Buyers from Fake Sellers

Fake sellers often target buyers who transact informally or skip identity checks.

A notary’s involvement forces the seller to prove who they are and what right they have to sell.

Treat document preparation the same way you treat money—handle it carefully.

A legitimate notary will:

- Check if the seller’s IDs match the name on the title

- Confirm the seller’s personal appearance

- Require a valid SPA for representatives

- Request supporting documents when something feels off

- Refuse notarization if ownership seems questionable

This blocks the most common types of scams:

- Someone selling property they don’t own

- Siblings or relatives selling without co-owner consent

- Middlemen claiming they are “authorized” when they’re not

- Sellers presenting fake or photocopied IDs

A fraudulent seller cannot survive a competent notary’s verification process.

Protecting Sellers from Fake Buyers or Scammers

ellers face fraud risks too, especially in transactions involving partial payments, staggered financing, or identity-sensitive documents.

Proper notarization protects sellers by:

- Confirming that the buyer is who they claim to be

- Documenting the buyer’s voluntary commitment to pay

- Establishing a timeline that supports forfeiture or enforcement clauses

- Preventing buyers from later denying their signature or agreement

- Securing the seller against claims of misrepresentation

Some buyers attempt to manipulate the process by:

- Using representatives without proper SPA

- Issuing bounced checks then claiming “I never signed anything”

- Attempting to reverse or dispute terms

A notarized DOAS or Contract to Sell makes these tactics significantly harder to execute—and far easier to defeat in court.

Why Notarization Is Often the First Line of Defense

Fraud is opportunistic. It looks for the first weak link in the transaction. When notarization is strict and proper, most fraud attempts collapse at the identity-verification stage.

Notarization prevents fraud because it creates:

1. A verified legal timestamp

This establishes when the sale happened. In double-selling cases, the notarized deed with the earlier timestamp usually prevails.

2. Public accountability

Documents entered into the notarial register become part of the court-supervised public record.

3. Traceability

Every notarized document can be traced back to the notary, the office, the signatories, and the IDs used.

4. Evidentiary strength

Notarized documents are presumed authentic unless proven otherwise.

The legal system respects notarized documents because they undergo controlled verification. Fraudsters avoid that environment—and succeed only when the process is bypassed.

Court Cases Where Notarized Documents Won the Dispute

Philippine jurisprudence is filled with real estate disputes that hinged not on who paid first, but on who held the properly notarized document.

Common scenarios where notarized documents prevail:

✔ Double Selling Cases

Courts typically favor the buyer with the earlier notarized DOAS because it demonstrates verified identity, voluntary agreement, and a legally documented timeline.

✔ Forged Signature Claims

A notarized document carries presumptive authenticity. Allegations of forgery require strong, often forensic-level evidence.

✔ SPA Validity Disputes

A properly notarized—and, for OFWs, apostilled or consularized—SPA is overwhelmingly more credible than informal authorizations or unsigned letters.

✔ Heir and Ownership Conflicts

Notarized waivers, deeds of donation, and affidavits have repeatedly overridden handwritten agreements presented by opposing parties.

✔ OFW Fraud Cases

Consularized SPAs protect OFWs from relatives or intermediaries acting without authority.

The judicial trend is clear:

In real estate disputes, notarized documents dominate unnotarized ones.

Fees, Timelines & OFW-Specific Policies

Notarization fees vary widely across the Philippines, but one truth remains constant: real estate documents cost more because the legal risk is higher. Millions of pesos move with every signature, and one defective notarization can freeze a transaction for months—or collapse it entirely. For OFWs, the stakes are even higher, as improperly authenticated documents often lead to invalid SPAs, failed sales, or exposure to scams.

This section breaks down the costs, timelines, and international rules every buyer, seller, investor, and OFW should understand before signing anything.

Typical Notary Fees (Metro Manila vs Regional Cities)

Notary fees are not regulated by a single national rate, so law firms and notaries price differently depending on location, demand, and document complexity.

Metro Manila (Higher Professional Fees)

- Affidavits: ₱150–₱500

- SPA: ₱500–₱1,500

- Real estate contracts (DOAS, CTS, Lease): ₱1,000–₱2,500+

- Corporate property documents: ₱2,500–₱5,000+

CBDs like Makati, BGC, and Ortigas charge more due to higher legal exposure and tighter compliance protocols.

Regional Cities (Generally Lower Fees)

- Affidavits: ₱100–₱300

- SPA: ₱300–₱800

- Real estate contracts: ₱600–₱1,500

While provincial fees tend to be lower, scrutiny from BIR and ROD is the same nationwide.

Why Real Estate Documents Cost More

More pages and multiple signatories

Additional checks (title numbers, tax declarations, addresses, payment details)

Stricter identity and voluntariness verification

Heavier legal responsibility for the notary

Higher risk of litigation (double selling, impersonation, forged SPAs)Real estate documents come with higher notarization fees because they involve:

Real estate documents come with higher notarization fees because they involve:

- More pages and multiple signatories

- Additional checks (title numbers, tax declarations, addresses, payment details)

- Stricter identity and voluntariness verification

- Heavier legal responsibility for the notary

- Higher risk of litigation (double selling, impersonation, forged SPAs)

Apostille vs. Consular Notarization for OFWs

OFWs handle more notarization-related issues than any other group, mostly because of confusion about what is considered valid in the Philippines.

A document notarized abroad is not automatically valid in Philippine agencies. It must go through either:

✔ Apostille Authentication

Used when the foreign country is part of the Hague Apostille Convention.

Process:

- Document is notarized locally abroad.

- It is authenticated by the issuing country’s Apostille authority.

- The apostilled document becomes legally valid in the Philippines.

Typical countries:

UAE, Japan, Australia, UK, Italy, South Korea, Singapore, Canada (recently), and many more.

Used for:

SPAs, affidavits, authorization letters, and other legal documents related to property.

✔ Consular Notarization (Philippine Embassy/Consulate)

Required when the country is not part of the Apostille Convention or when agencies require extra security.

Process:

- The OFW signs the document in front of an Embassy/Consulate officer.

- The document is notarized and authenticated directly by Philippine authorities.

Used for:

High-value transactions, real estate sales, SPA for DOAS signing, and any document where BIR/ROD insists on consular verification.

Common misconception to eliminate:

A document notarized by a foreign notary without apostille or consularization is invalid in the Philippines.

This is the root cause of countless failed transactions involving OFWs.

Comparison Table: “Apostille vs Consular Notarization”

| Category | Apostille Authentication | Consular Notarization (Philippine Embassy/Consulate) |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Basis | Hague Apostille Convention (1961) | Philippine consular authority (Department of Foreign Affairs) |

| Countries Covered | Accepted in 124+ member countries, including UAE, Singapore, Japan, Australia, UK, Canada, and most of Europe | All countries, including non-Apostille members (e.g., Qatar, Kuwait, China until 2023, most African states) |

| How It Works | Document is notarized locally abroad → authenticated by that country’s Apostille Authority | Document is notarized directly by the Philippine Embassy/Consulate abroad |

| Validity in the Philippines | Fully recognized by PH agencies (BIR, ROD, banks) as long as the issuing country is an Apostille member | Automatically recognized; considered equivalent to PH notarization |

| Typical Processing Time | 1–5 business days depending on the foreign country’s issuing agency | 3–14 business days depending on embassy workload and location |

| Cost Range | Varies by country (approx. US$10–US$50 per document) | Usually US$25–US$50 per document; varies per embassy |

| Best For | OFWs in Apostille-member countries needing SPAs, DOAS signings, affidavits | OFWs in non-Apostille countries or for situations requiring higher verification security |

| Accepted For | SPAs, DOAS, affidavits, lease agreements, bank loan documents, BIR filings, title transfers | Same as Apostille, plus cases requiring stricter authentication (certain banks or courts may prefer consular notarization) |

| Advantages | Faster, simpler, widely recognized; does not require Philippine embassy visit | Strongest form of overseas notarization; universally valid for all PH agencies |

| Limitations | Not valid if the country is not part of the Apostille Convention | Requires travel to or coordination with PH embassy; may have longer queues |

| Risk Scenarios if Not Done Properly | Apostille missing or done in non-member country → SPA/DOAS invalid in PH | Document notarized only locally abroad but not by PH Consulate → invalid despite looking “official” |

| Real Estate Use Case Examples | OFW in the UAE signing an SPA for a property sale; buyer in Singapore issuing an SPA for loan processing | OFW in Qatar or a country outside the Apostille Convention; high-value property transactions needing stronger verification |

Timeline for Overseas Documents to Reach PH Agencies

Even when the notarization is done correctly, timing becomes a critical issue for OFWs.

Estimated timelines:

Courier transit:

- DHL / FedEx / UPS: 3–7 days

- Regular international mail: 2–6 weeks

Processing in the Philippines:

- BIR (CGT/DST + CAR issuance): 2–6 weeks

- Registry of Deeds (title transfer): 3–8 weeks

- LGU clearances: 1–3 weeks

Real estate deadlines are unforgiving.

OFWs should always prepare documents 4–6 weeks ahead, especially when reservation expiries, loan approvals, or tax penalties are involved.

Risk Scenarios for OFWs (Invalid SPA, unsigned docs, etc.)

OFWs are the most common victims of failed notarizations and fraudulent representations, mainly because they transact remotely and rely on intermediaries.

Critical risk scenarios:

❌ SPA notarized abroad but not apostilled or consularized

Philippine agencies will immediately reject the SPA.

The representative has zero legal authority.

❌ Relatives or brokers signing documents “on behalf of the OFW” without proper SPA

Illegal, void, and a red flag for fraud.

This often leads to ownership disputes or double selling.

❌ OFW sends an unsigned DOAS home for “local notarization”

Impossible to notarize legally.

No personal appearance = void notarization.

❌ Using handwritten authorization letters

Worthless for real estate.

BIR and ROD will not entertain them.

❌ SPA that expired or contained incomplete details

A defective SPA invalidates every document signed under it.

Consequences for OFWs:

- Lost reservation fees

- Forfeited down payments

- Delayed or cancelled loan takeouts

- Failed title transfer

- Exposure to scams or forged transactions

- Legal disputes requiring travel back to the Philippines

The solution is simple but non-negotiable:

OFWs must use properly authenticated SPAs to avoid devastating financial losses.

Case Studies

Every year, countless property transactions derail because of one missing step: proper notarization. These short case studies reveal how small oversights create massive consequences—and how proper notarization could have prevented months of stress, legal battles, and financial loss.

Each story is based on real-world patterns repeatedly seen across Philippine transactions.

Title Transfer Rejected Due to Unnotarized DOAS

Carla thought she did everything right.

She paid the sellers in full. She received the keys. She even moved her family into their new home in Cavite. The sellers, wanting to speed things up, signed the Deed of Absolute Sale at home and handed it to her without notarization.

Everything fell apart at the BIR.

The examiner rejected her application on the spot:

- The DOAS was unnotarized

- No legal timestamp existed

- No presumption of authenticity applied

- No transfer could proceed

Takeaway:

If it isn’t notarized, the sale hasn’t legally happened—no matter how much you paid.

OFW Nearly Scammed Using an Invalid SPA

Mark, an OFW in Dubai, wanted to sell a vacant lot in Laguna. He drafted a Special Power of Attorney, had it notarized at a local UAE shop, scanned it, and emailed it to his cousin. The cousin immediately began “negotiating” with buyers.

A sharp-eyed buyer noticed a problem:

The SPA was not apostilled and had no consular notarization.

In the Philippines, it was worthless.

This discovery triggered further investigation—and it turned out Mark’s cousin was quietly speaking with another buyer, trying to secure a second, higher offer.

Had the transaction pushed through, Mark would have faced:

- A potential double-selling scandal

- Criminal liability

- Loss of control over his own property

- A legal dispute he’d have to resolve from overseas

Takeaway:

A foreign notarization alone has no legal effect in the Philippines. Without apostille or consular seals, your appointed representative has zero authority.

Land Dispute Resolved Because of Proper Notarization

Two brothers from Pampanga inherited farmland from their parents. Years later, a neighbor claimed ownership over a portion of the property using a faded, handwritten agreement allegedly signed by their late father.

The brothers responded with a properly notarized Deed of Donation, executed years earlier and entered into the notarial register.

In court, the difference was decisive:

- The handwritten document had no presumption of authenticity

- The notarized deed carried full evidentiary weight

- The judge accepted the notarized document as proof of their father’s genuine intent

The neighbors’ claim collapsed without ever reaching a lengthy trial.

Takeaway:

A notarized document can shut down disputes before they escalate—especially in inheritance and boundary conflicts.

Delayed Condo Sale Due to Mistakes in Notary Details

Julia was ready to sell her Quezon City studio unit and upgrade to a larger space. She and her buyer signed the DOAS at a neighborhood notary, expecting smooth processing. But the buyer’s bank flagged three critical issues:

- The notary’s commission had expired

- The seal didn’t match the official records

- The notary was operating outside their authorized city

Because of these red flags:

- The bank suspended the buyer’s loan

- Julia’s timeline to purchase her next unit collapsed

- Both parties had to redo the entire notarization process

What should’ve been a two-week closing turned into a four-week scramble.

Takeaway:

Even a “legal-looking” notarization can be invalid. The notary must be legitimate, current, and operating within the correct jurisdiction.

Frequently Asked Questions

Notarization is one of the most misunderstood parts of Philippine real estate. These authoritative, SEO-optimized answers address the questions buyers, sellers, OFWs, and investors ask most—without the legal jargon that usually makes these topics confusing.

Yes. Any document that transfers ownership—especially the Deed of Absolute Sale (DOAS)—must be notarized before the BIR, Registry of Deeds, and banks will process it.

Without notarization, the DOAS remains a private document:

✔ Valid between the parties

✘ Useless for title transfer

✘ Not acceptable for tax filing

✘ Weak in court

Supporting documents like SPAs and affidavits also need notarization to be recognized.

Absolutely—and they’re required to do so if something is legally questionable.

A notary must refuse when:

- The signer does not personally appear

- IDs are expired, inconsistent, or suspicious

- The document contains blanks, errors, or corrections

- The notary suspects coercion, fraud, or misunderstanding

- The venue is outside the notary’s jurisdiction

- The document is incomplete or illegal

A document becomes invalid—even with a stamp—when:

- The notary’s commission is expired

- Notarization was done outside jurisdiction

- The signer did not personally appear

- Fake, altered, or inconsistent IDs were used

- The notarial seal is incomplete or incorrect

- Pages, attachments, or annexes are missing

- The notary failed to record the act in the notarial register

Invalid notarization often results in BIR rejection, title transfer delays, or court disputes.

Not for real estate documents.

The Philippines does not allow online or remote notarization for:

- Deeds of Absolute Sale

- SPAs

- Contracts to Sell

- Lease agreements

- Affidavits used for tax or title transfer

Physical personal appearance is required.

For OFWs, notarization must be done through consular notarization or apostille authentication—not via DocuSign or online platforms.

No. Notarization validates the authenticity of signatures and voluntary execution—not the actual ownership of the property.

Ownership is transferred only when:

- Capital Gains Tax & Documentary Stamp Tax are paid

- BIR issues the CAR

- Registry of Deeds approves the title transfer

- A new TCT/CCT is issued under your name

A notarized DOAS is the first step, not the finish line.

Because the BIR checks both content and notarial compliance.

Common reasons for rejection include:

- Incorrect or missing notarial seal

- Notary acting outside jurisdiction

- Expired notarial commission

- Inconsistent names or ID details

- Missing annexes or attachments

- Invalid or unnotarized SPA for representatives

If the DOAS is defective, the BIR cannot compute taxes or issue CAR—delaying the entire transfer process.

Verify using this checklist:

- Commission certificate displayed

- Notarial seal with correct details (name, roll no., commission no., jurisdiction)

- Notary listed in the RTC’s roster of commissioned notaries

- Proper law office—not a mall kiosk or photocopy center

- Venue on the document matches the notary’s jurisdiction

If any of these fail, your notarization may be compromised.

No. Agencies require the original notarized copy for:

- BIR tax filing

- CAR issuance

- Title transfer at the Registry of Deeds

- Bank loan processing

Scanned copies may be used for assessment or pre-screening, but the original is always required for final transactions.

In most cases, no.

For real estate documents, notarization requires personal appearance, even if the signer executed the signature before arriving.

If the notary did not confirm identity and voluntariness in person, the notarization is void.

Yes—but only with a properly notarized and apostilled/consularized SPA.

Without this:

- Representatives cannot legally sign

- Notaries cannot notarize

- BIR and ROD will reject the documents

Representation without a valid SPA is treated as unauthorized signing.

No. It must be either:

- Consularized at a Philippine Embassy/Consulate

- Apostilled in a Hague Convention member country

Foreign notarization alone has no legal effect in the Philippines.

Yes—but only if:

- The notary personally compares the photocopy with the original

- The document is within their authority to certify

However, some documents cannot be certified by notaries:

- PSA documents

- Passports

- Government IDs

- Court-issued documents

These must be certified by the issuing agency.

No.

Notarization cannot cure:

- Illegal transactions

- Missing essential terms

- Unauthorized sellers

- Forged signatures

- Coerced signatories

A void contract remains void—even if notarized.

Acknowledgment

Used for contracts (DOAS, SPA). Signer acknowledges they executed the document voluntarily.

Jurat

Used for affidavits. Signer swears under oath that the statements are true.

Real estate documents typically use acknowledgment, not jurat.

Common reasons include:

- Notary with expired or invalid commission

- Wrong notarial venue

- Missing pages or annexes

- Incorrect notarization format

- Lack of personal appearance

- Inconsistent names and ID details

- Defects in the notarial seal

ROD examiners are extremely strict because they are the final gatekeepers before ownership is transferred.

The notarization itself does not expire, but:

- SPAs often include validity periods

- Some affidavits must be “recent” (e.g., within 3–6 months) for BIR or LGU

- Courts may scrutinize older documents if circumstances have changed

Always check if your document is time-sensitive.

Yes, but the challenger must present strong evidence. Because notarized documents have presumption of authenticity, courts require proof of:

- Forgery

- Fraud

- Coercion

- Notary misconduct

- Lack of personal appearance

- Fake IDs or impersonation

Without convincing evidence, courts uphold notarized documents.

Not legally required for validity—but strongly recommended because a notarized lease:

- Makes eviction and collection cases easier

- Strengthens legal enforceability

- Provides proof of tenancy for LGU or bank requirements

- Offers better protection for landlords and tenants

Most investors notarize leases to reduce risks.

No.

It proves that a document was executed properly—not that the seller truly owned the property.

Ownership is proven by:

- Title under the Registry of Deeds

- Valid chain of transfers

- Proper payment of taxes

- Successful issuance of a new TCT/CCT

Notarization supports ownership—but it does not create ownership.

Key Takeaways

- Notarization is your first line of legal protection in every Philippine real estate transaction. It gives documents the presumption of authenticity, blocks impersonation, and creates a verifiable legal timeline that government agencies and courts rely on.

- Critical real estate documents—DOAS, SPAs, affidavits, lease agreements, CTS—must be notarized for the BIR, LGU, banks, and the Registry of Deeds to process taxes, issue a CAR, or approve a title transfer. Without notarization, the sale is stuck, no matter how much has been paid.

- Fraud prevention begins at the notary’s desk. Fake sellers, forged signatures, invalid SPAs, and double-selling attempts collapse the moment a legitimate notary checks IDs, confirms identity, and enforces personal appearance. Proper notarization shuts down most scams before they start.

- Invalid notarization is as dangerous as no notarization. Errors like expired commissions, mismatched IDs, off-site signing, wrong jurisdiction, or incomplete documents lead to immediate rejection by the BIR or Registry of Deeds—and expose buyers and sellers to legal risks.

- OFWs face stricter rules. A foreign-notarized SPA is not automatically valid. It must be apostilled or consularized to be recognized in the Philippines. Without this, representatives have no legal authority, and transactions involving OFWs can collapse or be exploited by scammers.

Before you sign anything—before money moves, documents circulate, or negotiations progress—make sure you’re protected. Real estate transactions are too valuable to leave to guesswork, especially when one overlooked detail in notarization can delay, derail, or even invalidate an entire sale.

Whether you’re buying your first home, selling a property, handling documents for family members, or navigating a transaction from abroad, expert guidance ensures every step is legally sound and strategically executed

Buying or selling property soon?

Get personalized, end-to-end assistance on the documents, legal steps, notarization requirements, and due diligence you’ll need to complete your transaction smoothly and confidently.

Need help reviewing your DOAS, SPA, or real estate paperwork?

Reach out for document checks, risk assessments, and guidance tailored to Philippine laws—and avoid the costly mistakes most buyers and sellers only discover too late.

OFW or transacting remotely?

Get clear instructions on apostilles, consular notarization, and how to safely authorize someone to represent you in the Philippines.

Get clear instructions on apostilles, consular notarization, and how to safely authorize someone to represent you in the Philippines.

Your next real estate move deserves precision, protection, and professional support.

Message today to schedule a consultation or request help with your documents.

Leave a comment