A group of individuals discussing co-ownership agreements over property titles, highlighting the importance of clear documentation in real estate.

Co-ownership is one of the most common—and most misunderstood—forms of shared property ownership Philippines buyers enter into. Siblings buy a house together to reduce upfront cost. An OFW partners with a relative back home to secure a foothold in the Philippine market. Friends pool capital for a rental condo. Heirs inherit a family property and assume they’ll “sort it out later.”

The appeal is obvious. Shared capital lowers the entry barrier in a market where Metro Manila condo prices have risen steadily over the past decade and prime land has become increasingly scarce. For families, co-ownership feels natural. For investors, it promises leverage. For heirs, it happens automatically—no decision required. That’s the trap. The moment more than one name appears on a title, control fragments, rights overlap, and responsibility becomes collective, whether anyone planned for it or not.

What makes co-ownership particularly dangerous is the false sense of safety created by trust. “Magkakapamilya naman.” “Kaibigan ko ‘yan.” “Kami-kami lang.” Those assumptions collapse the moment money, exit timing, or authority enters the conversation. Courts do not enforce intentions. They enforce documents. In the absence of clear agreements, Philippine law defaults to rigid rules that often surprise even seasoned property owners—especially when income is involved, when one co-owner wants out, or when the property needs to be sold.

This guide is designed to show how co-ownership actually works in Philippine real estate—not how people assume it works. You’ll see how the law treats shared ownership, where rights and responsibilities begin and end, how income and exits are handled, and why many co-owned properties lose value despite being in good locations. More importantly, you’ll learn how to structure co-ownership deliberately, so it supports your financial and lifestyle goals instead of quietly limiting them.

“Most property disputes in the Philippines start with shared ownership.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- What Co-ownership Means in Philippine Real Estate

- Legal Foundation of Co-ownership in the Philippines

- Common Co-ownership Scenarios in the Philippines

- Types of Co-ownership Arrangements

- Rights of Co-owners You Actually Have

- Responsibilities and Financial Obligations of Co-owners

- Decision-Making Rules and Control Issues

- Income, Expenses, and Cash Flow Management

- Selling, Exiting, or Ending a Co-ownership

- Inherited Property and Heir Co-ownership Risks

- Red Flags That Signal a High-Risk Co-ownership

- Best Practices to Protect Yourself Before You Co-own

- Investment and Lifestyle Implications of Co-ownership

- Who Should—and Should Not—Enter Co-ownership

- Common Questions About Co-ownership in the Philippines

- Conclusion: Co-ownership Is a Legal Structure, Not a Relationship Test

What Co-ownership Means in Philippine Real Estate

Visual representation of co-ownership in Philippine real estate, illustrating a single property under one title shared by multiple owners.

Co-ownership in Philippine real estate occurs when two or more individuals legally own the same property under a single title. Each owner holds a share, but no one owns a specific room, floor, or portion of the land unless the property has been formally subdivided and issued separate titles. That distinction matters more than most people realize.

Legally, this arrangement is treated as an undivided interest property Philippines law recognizes as a single asset, regardless of how co-owners use or occupy it in practice. Your share exists on paper, not on the ground. Even if you contributed more capital, use the property more frequently, or manage it day to day, the law does not automatically convert physical control into ownership control. What it recognizes is what appears on the title and what is supported by proper documentation.

This is where many Filipino buyers and heirs are caught off guard. Seeing your name on a Transfer Certificate of Title or Condominium Certificate of Title feels conclusive. It isn’t. A title confirms that ownership exists—not who decides what. Decision-making authority, income rights, and exit options are governed by co-ownership rules, not by assumptions or informal arrangements. Without a written agreement, the law treats co-owners as equals in use and enjoyment, regardless of who contributed more time, effort, or emotional attachment.

Your name on the title confirms participation, not authority. Control in co-owned Philippine property comes from alignment, documentation, and agreed rules—not from occupancy, payment history, or seniority in the family.

Legal Foundation of Co-ownership in the Philippines

Co-ownership in the Philippines is not governed by custom, family hierarchy, or verbal promises. It is governed strictly by law. The moment two or more names appear on a property title, a legal relationship is created—whether the parties fully understand it or not.

At its core, Philippine co-ownership rests on a simple principle: one property, multiple owners, shared rights, shared obligations. The law is neutral by design. It does not favor the eldest sibling, the highest financial contributor, the person occupying the property, or the most assertive decision-maker. What it recognizes are documents, ownership proportions, and compliance with formal requirements.

This distinction becomes critical when there is no written co-ownership agreement Philippines courts can rely on. In practice, this is the norm rather than the exception. Most Filipino co-owners depend on informal arrangements, particularly within families. When disputes arise, courts do not attempt to reconstruct intentions or family dynamics. They enforce documents.

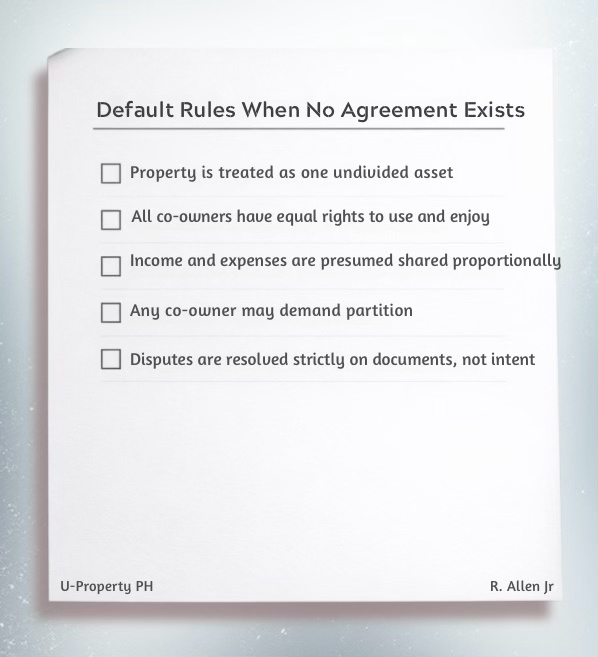

Why Courts Default to Documents, Not Intent

The default rules applied by courts are deliberately blunt. Ownership is presumed to be proportional to what is stated on the title or what can be proven through documented contributions. When contributions are unclear or unsupported by evidence, courts often treat all co-owners as equal. This is why disputes over “who paid more” frequently fail. Without receipts, bank trails, or written agreements, claims collapse quickly. The law protects certainty—not memory.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Ownership is based on title, not use

Verbal agreements carry minimal legal weight

Courts apply default rules when documents are missing

Ownership proportions must be proven, not asserted

Default rules for property co-ownership outlining rights and responsibilities.

Co-ownership without documentation does not create flexibility. It creates exposure. Philippine law will always choose clarity over compromise—even when the result strains relationships or destroys value.

Common Co-ownership Scenarios in the Philippines

Co-ownership rarely begins as a legal strategy. It begins as a response to constraint—limited capital, geographic distance, or circumstance. Across Philippine real estate, the same patterns repeat. Each starts with a reasonable intent and ends with a predictable risk profile.

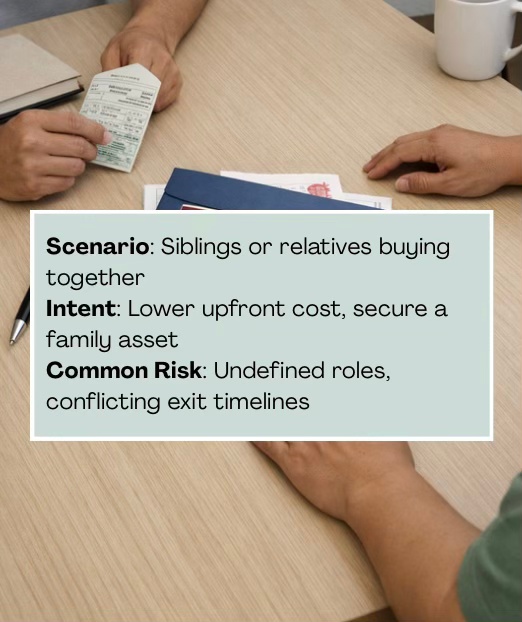

Joint Purchase by Siblings or Relatives

Intent

Reduce upfront cost and secure a shared family asset, typically a house-and-lot or a small condominium in Metro Manila or nearby growth corridors.

What goes wrong

Roles are never defined. One sibling pays the real property tax. Another occupies the home. A third wants to sell. Without a written agreement, everyone has rights—and no one has authority. Disputes surface when life changes: marriage, relocation, or financial pressure.

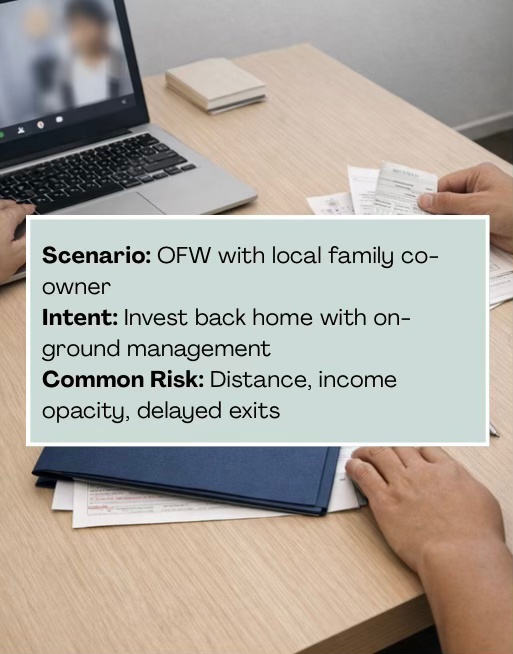

OFWs Buying With Local Family Members

Intent

Preserve hard-earned income by investing back home, relying on a trusted relative for on-the-ground management.

What goes wrong

Distance amplifies ambiguity. Rental income handling, maintenance decisions, and access to documents become friction points. When the OFW needs to exit, delays are common. Missed market windows matter where unrealized gains during disputes quietly disappear.

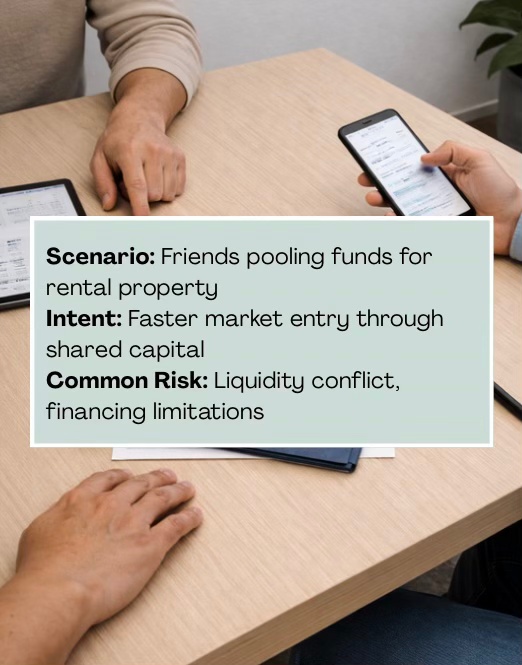

Friends Pooling Funds For a Rental Property

Intent

Enter the investment market sooner by sharing capital and risk, often targeting studio or one-bedroom units near central business districts.

What goes wrong

Professional expectations collide with personal relationships. One partner wants to reinvest cash flow; another needs liquidity. Financing options narrow because banks prefer clean ownership structures. The property may generate modest income, but resale becomes the choke point.

Inherited Property Among Heirs

Intent

None. This arrangement arises automatically. Heirs become co-owners by operation of law.

Intent

None. This arrangement arises automatically. Heirs become co-owners by operation of law.

Why These Scenarions Matter to Value

Across all four, the pattern is consistent. Co-ownership without structure delays decisions. Delayed decisions reduce liquidity. Reduced liquidity quietly erodes real ROI. Investors price this risk immediately. End-users feel it only when flexibility is needed—and discover it no longer exists.

Types of Co-ownership Arrangements

Not all co-ownerships are created equal. In the Philippine real estate market, outcomes depend less on who you co-own with and more on how the arrangement is structured. The law does not infer intent. It enforces it—but only when intent is documented. Understanding the core types of co-ownership is the difference between flexibility and long-term gridlock.

Types of Co-ownership at a Glance

| Arrangement Type | How It Starts | Best For | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Co-ownership | Joint purchase by buyers | Investors or families with clear agreements | Complacency and undocumented assumptions |

| Involuntary Co-ownership | Created by inheritance | Temporary holding before consolidation or sale | Long-term gridlock and title delays |

| Equal Ownership | Title reflects equal shares | Simple, truly equal contributions | Hidden imbalance and resentment |

| Proportional Ownership | Shares reflect actual contribution | Investment-driven partnerships | Poor record-keeping undermines enforcement |

| Temporary Co-ownership | Intended short-term holding | Bridge ownership or exit planning | Missed exit timing |

| Long-term Co-ownership | Designed to hold indefinitely | Family homes or stabilized rentals | Mismatched life changes over time |

Each of these structures behaves differently once income, control, and exit come into play.

Voluntary vs. Involuntary Co-ownership

Voluntary co-ownership arises by choice. Joint purchases by siblings, friends, or investment partners fall into this category. The advantage is control. Roles, ownership shares, income rules, and exit paths can all be defined from the outset. The risk lies in complacency. Because relationships feel stable at the beginning, documentation is often postponed. That is precisely when exposure is created.

Involuntary co-ownership arises without consent, most commonly through inheritance. Heirs become co-owners by operation of law, not by design. No strategy. No agreement. No exit plan. This is why inherited properties remain tied up for years, even in otherwise strong markets.

Equal vs. Proportional Ownership

Equal ownership appears fair on paper. In practice, it is frequently inaccurate. Contributions are rarely equal—cash input, loan exposure, ongoing expenses, and management effort almost always differ. When the title reflects equal shares but reality does not, resentment accumulates and disputes follow. Courts default to what is written, not to what feels equitable.

Proportional ownership aligns legal ownership with actual contribution. It requires discipline: accurate records, written agreements, and updates when contributions change. Investors favor this structure because it preserves economic logic and simplifies exits. Banks and buyers also view proportional ownership as lower risk.

Temporary vs. Long-term Arrangement

Some co-ownerships are designed to be transitional—holding a property until appreciation peaks or until heirs consolidate ownership. Others are intended to be long-term, such as family residences, legacy holdings, or stabilized rental assets. Problems arise when time horizons are mismatched. One owner plans to exit in three years. Another intends to hold indefinitely. Without a documented timeline or exit trigger, stalemates are inevitable.

Why Clarity of Intent Matters More Than Relationship

Filipino buyers often assume strong relationships reduce risk. In reality, the opposite is often true. Strong relationships delay difficult conversations. The law does not consider closeness. It considers whether intent was expressed, agreed upon, and recorded. Clarity protects relationships by removing ambiguity early. Ambiguity erodes both value and trust over time.

Rights of Co-owners You Actually Have

These rights exist by law, but their practical use depends on documentation, timing, and alignment among co-owners.

Co-ownership in Philippine real estate comes with rights that are clearly defined—but often misunderstood. These rights exist by law, not by permission from other co-owners. At the same time, each right has practical limits that matter in the real world, especially when money, timing, or exit plans are involved.

Right to Use and Enjoy the Property

Every co-owner has the right to use and enjoy the property in a manner consistent with its nature and without excluding others. Access to the house, unit, or land cannot be unilaterally denied. However, exclusive use by one co-owner without proper compensation or agreement often becomes a flashpoint. Occupancy does not confer control, and caretaking does not translate into superior rights.

Right to Income and Proceeds

If the property generates income—rent, lease payments, or sale proceeds—each co-owner is entitled to a share proportional to their ownership interest. This is where disputes surface fastest. When income is informal, undocumented, or controlled by one party, co-owners often discover they’ve been underpaid only after relations sour.

Right to Sell or Assign Your Share

A co-owner may sell or assign their undivided share without the consent of the others. This surprises many families and first-time co-owners. The limitation is economic, not legal. Buyers heavily discount undivided interests because they inherit complexity and future exit risk. Liquidity drops immediately.What is legally permitted is not always commercially sensible.

Right to Demand Partition

Any co-owner may demand partition—the legal separation or termination of co-ownership—at almost any time. This may be done voluntarily or through the courts. Partition is the ultimate exit mechanism and the most disruptive. Court-supervised sales frequently achieve below-market outcomes, which is why experienced investors treat partition as a last resort, not a strategy.

The Practical Limits That Change Everything

Rights on paper do not guarantee smooth execution. Exercising one right often interferes with another co-owner’s objectives. Use can conflict with leasing plans. Selling a share can impair overall value. Demanding partition can stall or freeze the asset for years. In practice, rights are most effective when supported by documentation, agreed decision processes, and aligned timelines.

Responsibilities and Financial Obligations of Co-owners

Obligations vs. Liability

| Obligation | Who Is Responsible to Pay | Who Is Legally Liable | What Happens If Unpaid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real Property Tax (RPT) | As agreed among co-owners | All co-owners | Penalties, interest, possible levy |

| HOA / Condominium Dues | Unit users or as agreed | All co-owners | Clearance issues, access restrictions |

| Utilities | Occupying co-owner | All co-owners | Service disconnection, resale delays |

| Maintenance & Repairs | As agreed or advanced by one | All co-owners | Deferred upkeep, value erosion |

| Government Fees & Clearances | Selling or designated party | All co-owners | Sale cannot proceed |

In Philippine real estate, liability attaches to the property—not to the most responsible co-owner.

Responsibilities—not intentions—determine whether a co-owned property functions as an asset or deteriorates into a liability. In Philippine real estate, obligations attach to the property itself, not to whoever appears most responsible at any given time. When one co-owner fails to pay, the consequences extend to everyone.

Obligations Attach to the Property, Not the Person

Shared Responsibility for Real Property Tax

Real Property Tax (RPT) is a joint obligation. Local government units assess the property as a whole; they do not pursue individual co-owners separately. When taxes go unpaid, penalties accrue, interest compounds, and the risk of levy or public auction increases. It is irrelevant who was “supposed” to pay. Every co-owner remains exposed. This is particularly damaging in growth areas, where rising property values lead to higher assessments while informal arrangements remain unchanged.

HOA or Condominium Dues and Utilities

For condominiums and properties within gated communities, association dues are mandatory. Arrears result in penalties, restricted access to amenities, and clearance problems during resale. Utilities follow the same principle. Even if only one co-owner occupies the unit, unpaid balances affect the entire ownership group. Buyers and banks identify these issues immediately. Clean cash flow is meaningless if clearance cannot be issued.

Maintenance and Repairs

Maintenance is where goodwill erodes fastest. Roof leaks, plumbing failures, and façade repairs do not wait for consensus. When one co-owner advances funds and others delay reimbursement, resentment accumulates. Over time, deferred maintenance reduces rental appeal, weakens pricing power, and accelerates value decline.

Liability Exposure When One Owner Fails to Pay

Here is the hard reality: third parties do not recognize internal agreements. Local governments, condominium corporations, service providers, and buyers treat co-owners as collectively responsible. When one co-owner defaults, the others must step in or absorb the consequences. This is why experienced investors insist on escrow arrangements, written cost-sharing rules, and clear enforcement mechanisms—even within families.

Decision-Making Rules and Control Issues

Who Decides What?” — Decision Authority in Co-owned Property

| Decision Type | Consent Required | Who Has Control | Common Conflict |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day-to-day use | Individual co-owner | Occupying co-owner | Assumed authority beyond use |

| Routine maintenance | Majority | Co-owners collectively | Disputes over reimbursement |

| Major repairs / renovations | Unanimous | All co-owners | Value vs. cost disagreements |

| Leasing the property | Unanimous | All co-owners | Short-term vs. long-term strategy |

| Selling the property | Unanimous | All co-owners | Exit timing deadlock |

| Mortgaging or encumbering | Unanimous | All co-owners | Financing blocked by one party |

Most co-ownership disputes arise when day-to-day control is mistaken for decision authority.

Control is where co-ownership either functions smoothly or breaks down entirely. In Philippine real estate, decision-making is neither intuitive nor democratic in the way families often expect. The law draws a clear line between ordinary use and acts that materially affect value, risk, or ownership. Cross that line without the proper consent, and disputes follow quickly.

What Requires Unanimous Consent

Major acts require full alignment. Selling the property, mortgaging it, entering long-term leases, or approving changes that materially affect value typically require the unanimous consent of all co-owners. A single dissenting owner can delay or completely block a sale. In practice, one holdout is enough to cause a property to miss optimal market windows—particularly in cities where price appreciation and rental demand move in cycles.

What Can Be Decided by Majority

Administrative and preservation matters—basic management, routine maintenance, and necessary repairs—are generally governed by majority rule. This appears empowering until it is tested. Majority decisions still require proper documentation and transparency. Without clear records, minority co-owners often challenge actions after the fact, especially when financial contributions are uneven. Majority control without process invites retroactive conflict.

Day-to-Day Use vs. Major Decisions

Using the property on a daily basis is not the same as controlling it. A co-owner who lives in the property does not acquire authority over leasing terms, renovation decisions, or future sale plans. Occupancy creates convenience, not command. This distinction frustrates many families, particularly when caretaking is mistaken for leadership. The law makes no such assumption.

Renovations, Leasing, and Resale Conflicts

Renovations occupy a gray zone. Minor repairs are routine; value-altering upgrades are not. One co-owner’s “improvement” can easily become another’s unrecoverable cost. Leasing presents similar tensions—short-term versus long-term tenants, pricing strategy, and income handling all require alignment. Resale is the pressure point. When timelines differ, exits stall. Investors anticipate this risk early; end-users usually encounter it only when it is too late.

Income, Expenses, and Cash Flow Management

Income and expense flow for co-owned property in the Philippines showing centralized account and proportional distribution

Cash flow is where co-ownership stops being theoretical. Titles and intentions fade once rent is collected and bills come due. In the Philippine real estate context, most co-owner disputes do not begin with ownership shares. They begin with who received the money, who paid the expenses, and who kept the records.

Rental Income Distribution

Rental income must be distributed strictly according to ownership share—not convenience. If a property generates ₱30,000 per month and ownership is split 60/40, distributions must follow that ratio every month, without exception. This discipline matters because margins are not wide enough to absorb informal handling, delayed remittances, or undocumented offsets.

Expense-Sharing Models That Work

The most reliable systems are deliberately boring. Either all co-owners contribute regularly to a shared account, or one party advances expenses with automatic, documented reimbursement. What fails consistently are ad hoc arrangements—settling “later,” reconciling at year-end, or netting expenses against rent without records. These shortcuts save time early and damage both cash flow and relationships later.

Documentation and Transparency Standards

Sound documentation is not a sign of distrust. It is a continuity safeguard. Every peso moving in or out of the property should be traceable through bank deposits, receipts, invoices, and simple monthly summaries. This discipline becomes critical during resale, audits, or disputes. Buyers, banks, and courts rely on paper trails. Transparency protects the quiet co-owner as much as the active one.

Tax Implications of Shared Rental Income

Rental income is taxable regardless of how informally it is handled. Each co-owner remains responsible for declaring their proportional share. When one person collects rent and fails to issue proper documentation, all co-owners are exposed. Tax non-compliance most often surfaces during a property sale—precisely when clean records suddenly matter. Investors account for this risk early. Casual co-owners usually discover it too late.

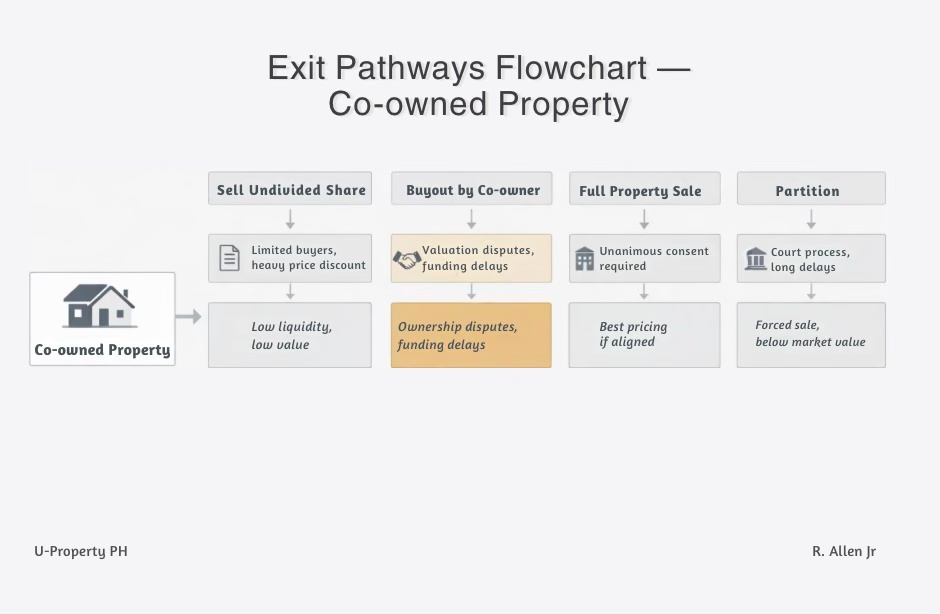

Selling, Exiting, or Ending a Co-ownership

Most value loss in co-ownership happens not at entry, but at exit—when alignment breaks down.

Every co-ownership eventually faces the same question: How do we get out?

In practice, selling co-owned property Philippines transactions require a level of alignment that many ownership groups underestimate—until options have narrowed. Exits are rarely simple. Exit mechanics, not intent, determine whether value is preserved or quietly destroyed.

Why Exit Planning Matters More Than Entry

Selling an Undivided Share

A co-owner has the legal right to sell their undivided share without the consent of the others. This often surprises families and first-time co-owners. In practical terms, however, this option is weak. Buyers heavily discount undivided interests because they inherit uncertainty, lack control, and face future partition risk. Liquidity drops immediately. What is legally permissible is frequently economically unattractive, particularly in markets where clean titles and decisive ownership drive pricing.

Right of First Refusal Explained

Many co-ownership agreements include a right of first refusal (ROFR), allowing existing co-owners to purchase a departing owner’s share before it is offered to third parties. When properly documented, ROFR preserves value and keeps ownership consolidated. When informal or verbal, it collapses under pressure. Courts enforce what is written—not what was “understood.”

Full Property Sale With Multiple Owners

Selling the entire property typically delivers the highest value—but only when all co-owners agree. A single dissenting owner can delay or completely block the transaction. In appreciating markets, timing is critical. Missing a peak cycle can erase gains equivalent to several years of rental income.

Buyouts and Valuation Disputes

Buyouts appear clean until valuation enters the discussion. Who determines the price—market appraisal, historical cost, or emotional premium? Without a pre-agreed valuation method, buyouts quickly become adversarial. Transactions stall not because parties dispute ownership, but because they dispute numbers. Experienced investors predefine valuation formulas. Families often do not—and pay for it later.

Partition: Extrajudicial vs. Judicial

Partition is the legal endgame. Extrajudicial partition works only when all co-owners cooperate. Judicial partition is compulsory and slow. Courts may order physical division (rare) or sale through public auction (common). Auction outcomes frequently fall below market value. Partition resolves deadlock—but it is a blunt instrument, not a value-maximizing strategy.

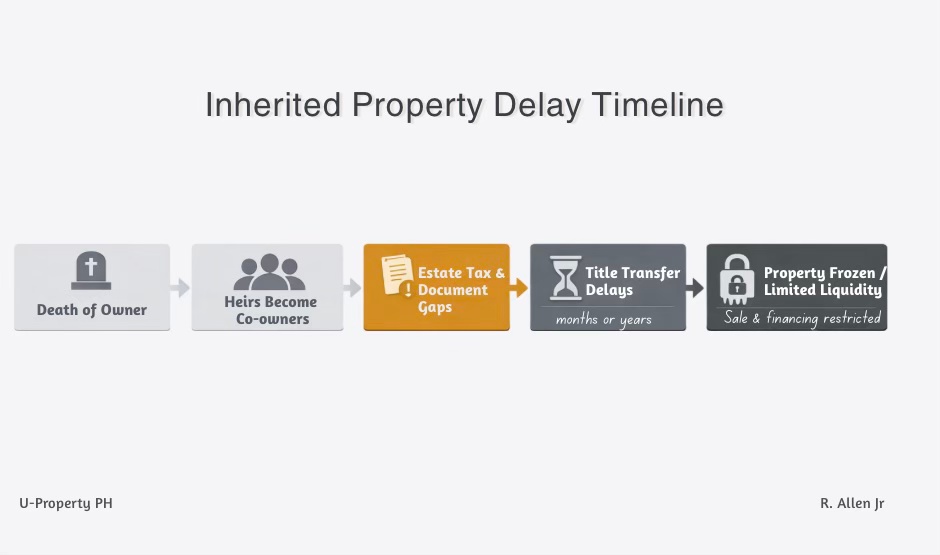

Inherited Property and Heir Co-ownership Risks

This delay is not accidental—it is the default outcome when estates remain unresolved.

Inherited property is the most common—and most dangerous—form of co-ownership. This form of heir property co-ownership Philippines families encounter is rarely planned and almost never documented at the outset. Not because heirs make poor decisions, but because inheritance creates co-ownership automatically, often without planning, documentation, or alignment.

Inheritance Creates Owners, Not a Plan

Why Inheritance Automatically Creates Co-ownership

When a property owner passes away, ownership does not transfer to a single heir by default. It transfers to all heirs collectively. Until the estate is settled and titles are transferred, heirs hold the property in common. No one can sell cleanly, no one can mortgage it independently, and no one truly controls it. What begins as a family asset can quickly turn into a legal holding pattern.

Estate Tax and Title Transfer Delays

Estate settlement is rarely swift. Even with amnesty programs and simplified procedures, delays are common. Missing documents, unpaid estate taxes, and unresolved heir issues routinely stall the process. During this period, the property remains legally unsellable. It cannot fully participate in the market. Rental income may continue, but capital appreciation is effectively frozen from a realizable standpoint.

How Unresolved Estates Freeze Property Value

This freeze carries real financial consequences. Years pass. Market cycles move. When the property finally becomes transferable, the optimal exit window may already have closed. Lost value is rarely recovered, and holding costs accumulate quietly in the background.

When Consolidation or Sale is the Smarter Move

There comes a point when sentiment must give way to strategy. Consolidating ownership under one heir through buyouts, or selling the property outright and distributing proceeds, often preserves far more value than prolonged co-ownership. This is especially true when heirs live abroad, have differing financial priorities, or lack interest in active management. Holding for the sake of holding is not a plan.

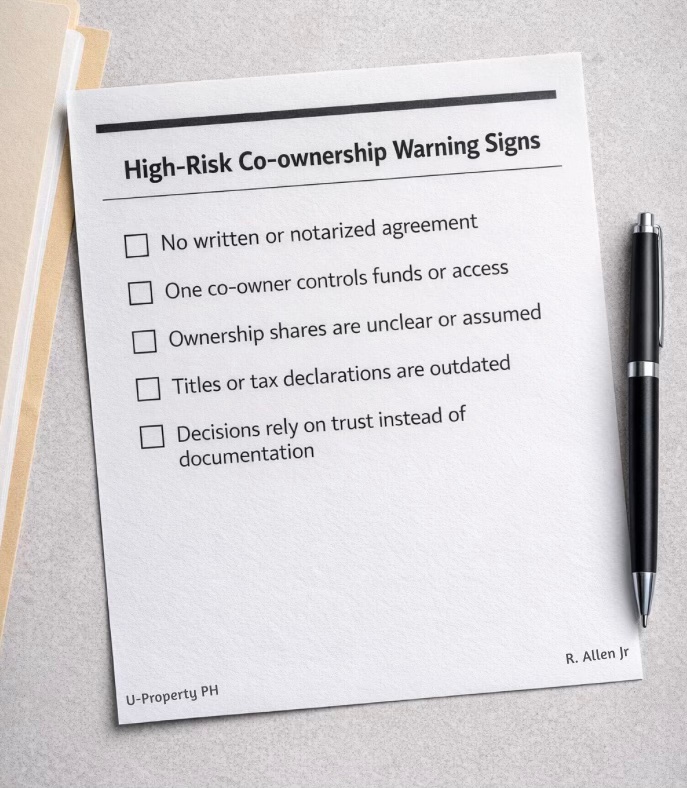

Red Flags That Signal a High-Risk Co-ownership

When two or more of these conditions exist, co-ownership risk compounds quickly.

High-risk co-ownerships are easy to identify—once you know what to look for. The problem is that most owners recognize these warning signs only after value has already been lost. These red flags consistently precede disputes, stalled transactions, and forced exits at discounted prices.

No Written Agreement

This is the most common—and most costly—mistake. Without a written and notarized agreement, default legal rules apply. Those rules are rigid and indifferent to intent. Verbal understandings carry little legal weight, particularly when money or exit decisions are involved. If it isn’t written, it isn’t enforceable.

One Person Controlling Funds or Access

When a single co-owner collects rent, pays expenses, or controls access to the property and its documents, imbalance sets in. Even when justified as “convenience,” this concentration of control creates opacity. Disputes typically surface when income distribution is questioned or when transparency is requested. Transparency delayed is conflict accelerated.

Unclear Ownership Shares

Equal names on a title do not always reflect equal contributions. When ownership shares are assumed rather than documented, resentment accumulates quietly. Courts and buyers rely on what is provable, not on what feels fair. In transactions, ambiguity equals risk—and risk translates directly into price discounts.

Outdated Titles or Tax Declarations

Titles not updated after inheritance, name changes, or transfers are not minor clerical issues—they are transaction blockers. The same applies to outdated tax declarations. In the Philippine real estate market, clean documentation is a prerequisite for sale, financing, and even serious buyer engagement. Delays here routinely freeze otherwise marketable assets.

Emotional Decisions Replacing Documentation

Statements such as “we’ll fix it later,” “family naman,” or “sayang pag-usapan” are not harmless. They signal that decisions are being driven by emotion rather than structure. Markets do not reward sentiment. They reward clarity. Emotional avoidance today almost always becomes legal conflict tomorrow.

Best Practices to Protect Yourself Before You Co-own

Co-ownership works only when it is engineered deliberately. The difference between a durable shared asset and a slow-moving dispute is almost always preparation. Structure is what controls risk.

Structure Is Prevention, Not Formality

Written Co-ownership Agreement Essentials

A written and notarized co-ownership agreement is non-negotiable. At a minimum, it should clearly define ownership percentages, income distribution, expense sharing, management authority, and voting thresholds. This document functions as the operating manual of the property. Without it, default legal rules apply—and those rules exist to resolve disputes, not to preserve value.

Clear Exit and Dispute Clauses

Every co-ownership should assume that someone will eventually want out. Exit clauses determine how that happens without conflict. Rights of first refusal, valuation methods, timelines, and payment terms should be agreed upon while interests are still aligned. Dispute clauses—mediation first, litigation last—reduce the risk that disagreements escalate into frozen assets or forced sales.

Bank Accounts and Record-Keeping

Shared properties require shared systems. Rental income and expenses should flow through a dedicated bank account, not personal wallets. Monthly summaries, receipts, and simple ledgers protect all parties. This discipline becomes critical at exit. Buyers, banks, and tax authorities consistently favor properties with clean, traceable financial records.

When to Involve Lawyers, Brokers, or Accountants

Professional input is most effective early. Lawyers formalize ownership, governance, and exit mechanisms. Brokers provide market-based valuation, liquidity insight, and timing guidance. Accountants ensure income reporting and tax compliance. Involving professionals only after disputes arise is reactive—and far more expensive. Early advice is a controllable cost; late advice is damage control.

When to Avoid Co-ownership Entirely

Co-ownership is not universally appropriate. It should be avoided when timelines are mismatched, capital contributions are unclear, decision-making styles conflict, or documentation is repeatedly deferred “for now.” If clean exits, flexibility, and speed matter, solo ownership or properly structured corporate vehicles are often better fits. Walking away early is sometimes the most effective form of risk management.

Investment and Lifestyle Implications of Co-ownership

Solo Ownership vs. Co-ownership (Investment Lens)

| Factor | Solo Ownership | Co-ownership |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Full decision authority | Shared decision authority |

| Liquidity | Easier and faster resale | Slower resale, alignment required |

| Exit Flexibility | High | Limited by co-owner consent |

| Financing Access | Broader bank options | More restrictive lending |

| Cash Flow Handling | Direct and centralized | Requires agreed structure |

| Risk of Deadlock | Minimal | Elevated without documentation |

| Resale Pricing | Market-driven | Often discounted for complexity |

| Investor Appeal | High | Selective and risk-adjusted |

These differences explain why co-owned properties behave differently at resale, even in strong locations.

Co-ownership alters both the economics and the lifestyle calculus of a property. Occasionally for the better. More often, quietly for the worse. When liquidity, clean titles, and execution speed matter—as they do in most Philippine real estate transactions—shared ownership reshapes outcomes in ways buyers frequently underestimate.

Impact on Liquidity and Resale Value

Liquidity is the first casualty. Properties with multiple owners take longer to sell because every material decision requires alignment. Buyers price that friction in immediately. Even in prime urban locations, co-owned assets often trade at a discount relative to comparable solo-owned properties simply because exits are harder to execute. When timing matters—and it always does—co-ownership narrows the window. Missed cycles can erase gains equivalent to several years of rental income.

Bank Financing Limitations

Banks favor simplicity. Clean ownership structures reduce underwriting risk. Co-owned properties, particularly those without clear agreements, face heightened scrutiny. Loan approvals may require unanimous consent, additional documentation, or may be declined entirely. This constrains leverage and shrinks the future buyer pool. Reduced financing access translates directly into weaker demand at resale.

Suitability for Rentals, Family Use, or Vacation Homes

Co-ownership performs very differently depending on use case.

- Rentals: Viable when income distribution, expense handling, and exit rules are clearly documented.

- Family use: Emotionally appealing but operationally fragile. Lifestyle decisions collide quickly when ownership is shared.

- Vacation homes: High-risk unless usage schedules and cost-sharing mechanisms are explicit. Idle time often becomes a source of dispute rather than rest.

Why Investor Treat Co-ownership Cautiously

Professional investors are not opposed to co-ownership; they are opposed to uncertainty. Risk is priced ruthlessly. Undivided interests, unclear exit paths, and financing constraints all compress expected returns. This is why experienced investors either formalize co-ownership aggressively or avoid it entirely. On paper, the numbers may work. Execution risk is what kills deals.

Who Should—and Should Not—Enter Co-ownership

Buyer Profile Match: Co-ownership Suitability

| Buyer Profile | Co-ownership Fit | Why It Works / Doesn’t | Key Risk to Watch |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-time buyers pooling funds | Conditional | Improves affordability but limits flexibility | Exit timing conflict |

| Siblings or close family | Conditional | Trust exists but roles often undocumented | Emotional deadlock |

| OFWs with local partners | Conditional | Capital + on-ground presence | Income opacity |

| Friends investing together | Limited | Capital aligned, goals often diverge | Liquidity disputes |

| Heirs holding inherited property | Temporary | Works only with clear exit plan | Title stagnation |

| Solo end-users | Poor fit | Full control preferred | Forced compromise |

| Long-term passive investors | Poor fit | Liquidity and control matter | Resale discount |

Co-ownership works best when structure—not sentiment—matches the buyer profile.

Co-ownership is not a moral choice. It is a structural one. It works well for certain profiles and creates long-term friction for others. Identifying where you fall before signing anything is the most practical form of due diligence.

Profiles That Benefit From Shared Ownership

Co-ownership performs best when expectations, timelines, and risk tolerance are aligned. Typical profiles that benefit include:

- Investors with defined exit plans, clear contribution records, and agreed valuation methods. In urban markets where rental yields average 4%–6% annually, disciplined partners can preserve both income stability and exit flexibility.

- Heirs who plan early consolidation or sale rather than prolonged holding. Temporary co-ownership with a clear endpoint limits value erosion and reduces conflict.

- OFWs with formal management structures, documented income handling, and professional oversight. Distance is manageable when systems, not assumptions, are in place.

- Family members with similar financial capacity and decision styles, supported by written agreements and neutral governance processes.

Profiles That Should Avoid Co-ownership

Shared ownership becomes high-risk when structure is replaced by hope. Co-ownership should be avoided by:

- Buyers who require fast liquidity or clean resale, especially in markets where timing directly affects pricing.

- Individuals uncomfortable with documentation, accounting, or formal agreements, where avoidance leads to exposure.

- Groups with mismatched timelines, such as one party planning to hold long-term while another needs flexibility.

- Relationships already strained by money, even before property enters the equation.

Self-Assessment Questions Before You Co-own

Before proceeding, ask yourself:

- Can I exit without relying on goodwill?

- Are ownership shares and contributions clearly documentable?

- Would I be comfortable enforcing rules against someone I know?

- If the property needed to be sold within two years, would everyone agree?

If any answer is unclear, the structure is not ready.

Common Questions About Co-ownership in the Philippines

Can a co-owner sell a property without the consent of the others?

A co-owner may sell their undivided share without consent, but not the entire property. In practice, buyers heavily discount undivided interests because they inherit uncertainty and exit risk.

Can one co-owner block the sale of a co-owned property?

Yes. A full property sale typically requires unanimous consent. One dissenting co-owner can delay or completely block a transaction, even in a strong market.

Is a co-owned property eligible for bank financing in the Philippines?

Sometimes. Banks generally prefer clean ownership structures. Co-owned properties may face stricter requirements, additional documentation, or outright rejection depending on risk assessment.

What happens if one co-owner refuses to cooperate?

Any co-owner may ultimately demand partition. This can lead to court-supervised sale or division, which often results in lower-than-market outcomes.

Conclusion: Co-ownership Is a Legal Structure, Not a Relationship Test

Co-ownership is neither inherently good nor bad. It is a legal structure with predictable consequences. When designed deliberately, it can unlock opportunity—shared capital, controlled risk, and access to assets that might otherwise be out of reach. When left informal, it becomes one of the fastest ways to trap value inside a property.

The pattern is consistent. Trust may start the deal, but documentation determines the outcome. Courts, banks, and buyers do not evaluate relationships. They evaluate titles, agreements, tax records, and financial trails. This is why so many co-owned properties underperform despite being located in strong markets.

The takeaway is simple and non-negotiable: documentation beats intention every time. Clear ownership shares, defined decision rules, transparent cash flow, and planned exits are not expressions of distrust. They are expressions of respect—for the asset and for the people involved. Good structure protects relationships by removing ambiguity before it becomes emotional or adversarial.

Professional guidance is not an added cost. It is risk mitigation. Lawyers formalize rights and exit mechanisms. Brokers protect market timing and liquidity. Accountants preserve income integrity and tax compliance. Engaging professionals early is how co-ownership remains a strategy—not a problem that surfaces years later when options are limited.

If you are considering co-ownership—or already inside one—the time to act is now, while cooperation still exists. Clarify roles. Document terms. Align timelines. In Philippine real estate, value is preserved not by trust alone, but by structure that holds when trust is tested.

The Three Pillars of Safe Co-ownership

Structure

Clear ownership shares, defined roles, and decision rules

Documentation

Written agreements, updated titles, clean records

Exit Planning

Predefined buyouts, sale triggers, and valuation methods

When any one of these pillars is missing, co-ownership risk multiplies.

Protect Your Property Before Problems Start

Co-ownership problems do not announce themselves. They surface when a sale stalls, income is questioned, or one owner needs out—and by then, leverage is gone. The smartest move is preventive, not reactive.

If you’re a buyer:

Confirm whether co-ownership is the right structure before your name goes on a title. A short review now can save years of deadlock later.

If you’re an investor:

Protect liquidity, pricing power, and exit timing. Structure shared ownership the way the market expects—or expect the market to discount you.

If you’re an heir:

Unresolved estates quietly destroy value. Early consolidation or a clean sale preserves options and reduces family strain.

If You’re Already Co-owning, Timing Still Matters

Co-ownership problems do not announce themselves. They surface when a sale stalls, income is questioned, or one owner needs out—and by then, leverage is gone. The smartest move is preventive, not reactive.

Choose your next step:

- Book a consultation to review your co-ownership setup or proposed purchase

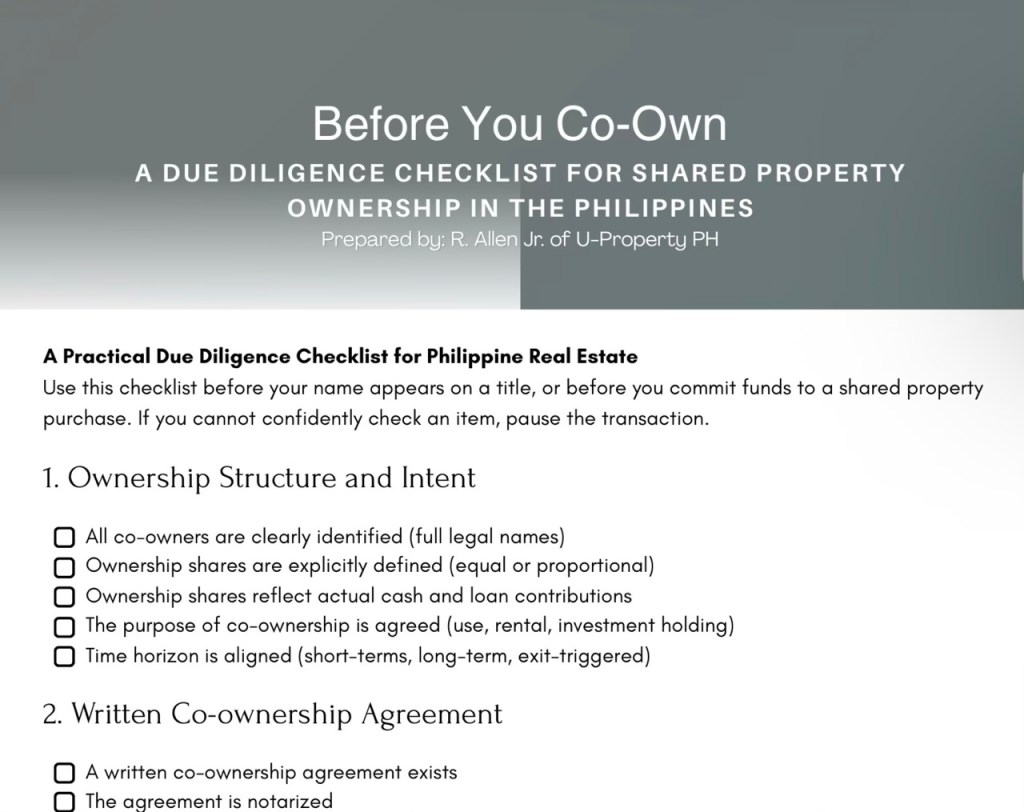

- Download the “Before You Co-own” checklist to stress-test risks in minutes

- Request a due diligence review to identify red flags before they become permanent

Leave a comment